The housing prospects for young people in the UK were completely changed by the global financial crisis of 2007-09.

While the government largely succeeded in rescuing the banks and the housing market, it created an environment where house prices remained high and mortgages were only available to those who could afford hefty deposits. As a result, many young people who might have got a foot on the property ladder were forced to keep renting.

While this has prompted much concern in recent years about the prospects for “generation rent”, the flipside is that it created an investment opportunity. To meet the demands of this demographic, property investors started putting billions of pounds into a new housing class known as build-to-rent (BTR).

To understand this shift, we’ve been researching the rise of these properties in one of the UK’s leading cities, Manchester. It demonstrates a change in the kinds of organisations that own UK homes, and some difficult implications for those who rent them.

The new property boom

The residential rental market used to be mainly made up of buy-to-lets, which are typically owned by small-scale landlords who have a relatively small number of properties in their portfolios. Build-to-rent, on the other hand, refers to large blocks of housing units owned by institutional investors such as pension or investment funds.

This housing class has grown significantly over the past ten years: by the end of 2022, it accounted for over 240,000 units built or under construction in the UK. Property group Savills predicts that this will increase fivefold over the next decade.

These new corporate landlords were attracted by the fact that they could earn a high yield on their investment from rents (at least when interest rates were low). There were also valuable economies of scale in marketing, managing and maintaining multiple blocks of flats that were all in the same area.

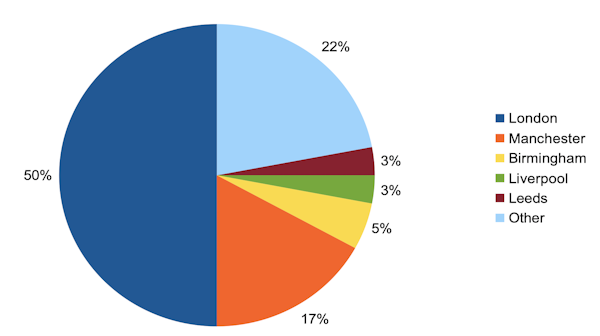

London is the largest market for this kind of property in the UK, accounting for about 50% of completed BTR properties. But as our recent paper shows, its presence is growing in cities like Manchester. In the city regional centre, which includes Manchester city centre, Salford Quays, central Salford and the Pomona area of Trafford, out of 45,000 new housing units built between 2012 and 2020, 22,984 were BTR. That’s just short of one-fifth of the national total.

UK build to rent by city

Role of the public sector

Both the UK government and city councils have been instrumental in helping the build-to-rent market to take off. The government made a £1 billion BTR fund available to investors between 2012 and 2016 to underwrite their projects, as well as making it easier for them to get planning permission thanks to the 2018 National Planning Policy Framework.

In Manchester, local policymakers also funnelled national subsidies towards these investors: Greater Manchester’s Housing Investment Fund initially lent out £167 million to six high-profile developments.

A more indirect subsidy has been the relaxation of affordable housing requirements. Between 2012 and 2020, developers in central Manchester and the nearby areas of Salford and Trafford only contributed £15.4 million in the “section 106” payments used to build such properties. Given that there was an £8.3 billion investment into BTR over the same eight-year period, this is a very small amount.

Overall, we found that only 471 new homes in the city-regional centre out of 45,000 have been classed as “affordable” by government criteria, meaning that the city’s residential boom has been dominated by private sector market rental housing. According to policy guidance, 20% of new units are supposed to be affordable. Developers in the centre are clearly not contributing to these targets.

Following the money

These highly conducive conditions helped attract a variety of new financial players. Given that they can choose to sell these properties on or to hold them, including revaluing them upwards in future as a way of booking profits, it has attracted players with different investment strategies and risk appetites. From our research into Manchester, 39% of BTRs have been built by non-listed property funds, while 24% are listed funds, 14% are pension and insurance funds and 9% are from investment banks.

Two-thirds of the money came from overseas, including from North America, the Middle East, China and Europe. Some of the money is registered in tax havens such as the Cayman Islands. We developed this interactive map with the Open University to make it easy for people to see these relationships – you just click on a marker for a given development to follow the money.

Build-to-rent properties undoubtedly meet an urgent need: in a context of dwindling housing supplies and high inflation, there are many young people without the means to save for a deposit or buy a house. But it also transfers the capital gains that they would have enjoyed as homeowners to corporate landlords, often located outside the UK.

This exacerbates wealth inequalities by making it harder for these renters to keep pace with those who already own properties as prices rise. At the same time, the lack of affordable housing may exclude established communities as rents are pushed up further around the city centre.

The government and local authorities have tried to create the most beneficial climate for BTR investors. But this raises questions about the loss of local democratic control over development, as urban landscapes are liable to become shaped by the investment preferences of powerful new players rather than local need.

Devising a workable alternative is our next research project. But in the broadest terms, we need an urban development model built on a new compact between national and local state organs to build good quality social and affordable housing where the benefits would be recycled locally, rather than drifting off to tax havens.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.