One of the almost universal benefits of students’ unions and their equivalents around the world – insofar as they are pretty much all democratic in character – is that they offer an opportunity to learn how to participate in politics.

And as such, in many ways, their democratic structures tend to mirror those of their nation – sometimes by accident, and sometimes (in the case of say, Finland), by law.

Austria has a robust democratic culture at federal, state and municipality level and has a mutli-party system that sees coalitions form following a big ballot.

And that’s pretty much how both the national union and local SUs work too. Students don’t elect individuals into jobs – they vote for parties, seats are distributed and then leaders of activity, project work and representation appointments are determined in coalition talks.

It means that the whole system feels very factional and much more “political” than we might see in the UK – but that doesn’t mean that what we might call “students as students” issues are being ignored. In fact it gives them a real educational edge.

We want to make the university and the world a better place

Leading the coalition right now at the University of Vienna are the Association of Socialist Students in Austria (VSStÖ), which was established as far back as 1893 to advocate for open access to higher education and a democratic university structure, while also criticising “bourgeois science”.

It was significant in the campaign for universal suffrage and opposing the First World War, all of which led to their temporary ban during the conflict. Today it has a clear agenda for the future of education and universities, offers advice to students on their rights and offers students the chance to build political understanding and belonging in a system that is not strong on clubs and associations.

Crucially, it’s easy to see how participants in the process – as voters, candidates or factional supporters – are learning some of the skills necessary for later participation in democratic life. The coalition agreement resulting from the last election at Vienna is an impressive piece of policy work – covering everything from campus food to coming to terms with the “fascist history” of the university – and gives students a real sense not just of the functional and service role of the union, but its priorities for change too.

One of the upshots of a system like this is that the coalition process always generates a breadth of activity – and however radical or “woke” that SUs’ agendas are, it also means that right wing parties and agendas are represented at least in the election too.

It’s not so long ago that conservative ÖVP-affiliated groups (think business, farmers and the Roman Catholic Church) tended to win nationally – but since 1995 it’s tended to be coalitions on the left, centre left, environmentalists and independents that have run the ÖH nationally.

If nothing else, the process means that most of the parties nurture a youth and student wing, and so the concerns of universities and students become much harder than they are in the UK to ignore when main elections come around.

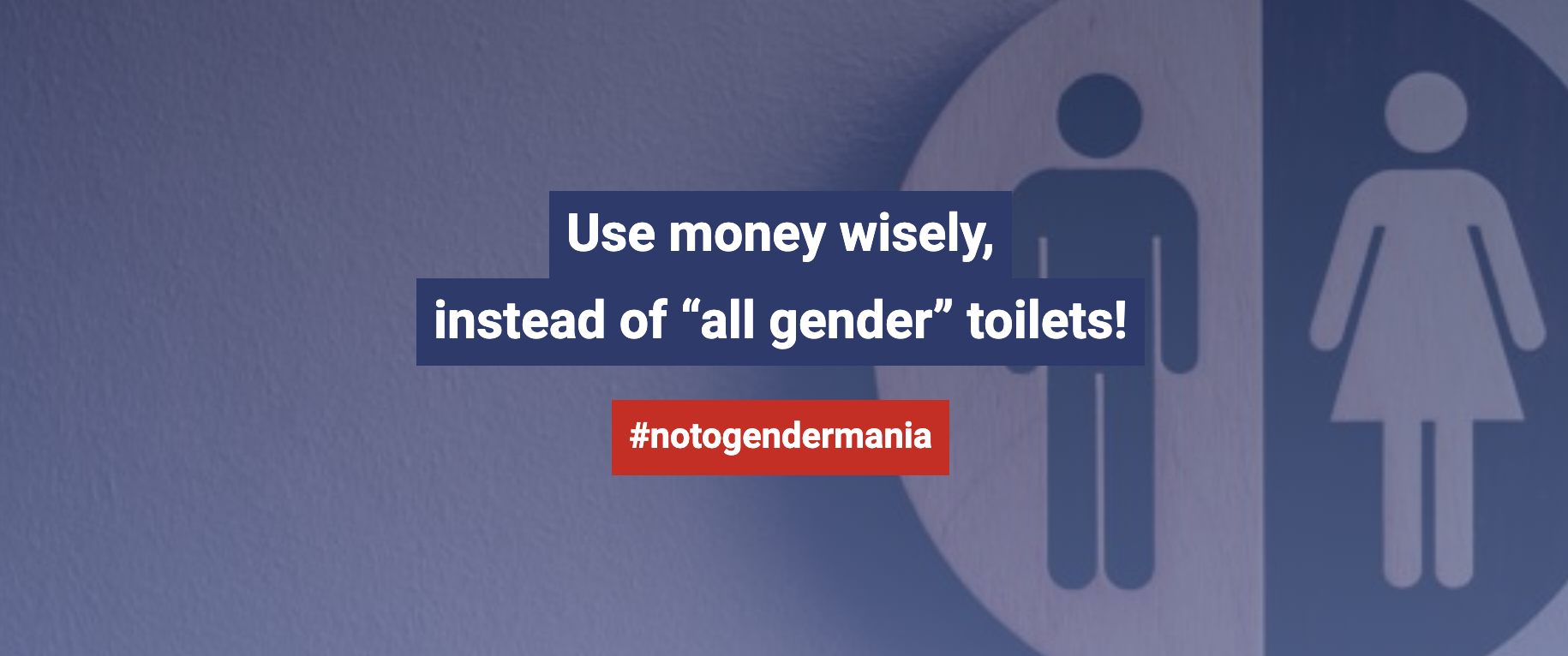

And the way in which it formally platforms what would often be considered controversial views – the populist Ring of Freedom Students (RFS), for example, has a campaign against “gender madness” and Covid restrictions – means that universities and SUs can never be accused of imposing wokery on students, because the process demonstrably works the other way around.

Even in small universities like Leoben, the politics of coalition building and the fall out from elections generates considerable interest and press coverage – and in the long-term, considerable legitimacy for the student movement in the process.

Self-appointed moralizers patronising other students

Culture wars are a thing here – and as in other countries across Europe, right-wing populists are on the rise, where it’s Germany and Austria’s fraternity associations that provide the most fertile ground for recruitment. That means that the extreme left-right bifurcation by age that we see in the two party politics of Westminster isn’t really present at all.

The way in which both that and wider Austro-German politics have fed into the student movement’s response to Israel/Palestine is fascinating. It’s the Association of Socialist Students, Greens and Communists in charge at ÖH Vienna – so it was surprising from a UK perspective to see such unequivocal views on some of the “slogan debates” that have taken hold across campuses here and at home.

Across the university, graffiti with slogans like “free Palestine from Austrian/German guilt”, “from the river to the sea”, and “Intifada” have been popping up – but in ÖH Vienna’s view, these phrases represent criticism and antagonism towards Israel and so are antisemitic:

These expressions, using Israel-related antisemitism, are often perceived as legitimate criticism of the state of Israel and not as antisemitic. The demonizations of Israel should be classified as clearly antisemitic and must be condemned. We must not turn a blind eye to left-wing antisemitism, especially when it manifests in actions that further impair the sense of security of Jewish students at the university. Leftist groups that trivialise or even promote antisemitic tendencies cannot be allies in the fight for a safe university for all.

Something else that’s interesting about the scaffolding of this student political system is the way in which it produces policy and positions on issues (and not just at election time) that end up having significant influence both within universities and wider political debate.

The national union’s Fighting for the education of tomorrow paper includes proposals for reforming teacher training, revised rules on the duration of bachelor’s and master’s programs, improved curriculums that incorporate more practical training, and the involvement of students in educational governance.

Improving the everyday situation of students

As we saw across the Balkans, project funding is important here too. As well as distributing the compulsory SU fee to local ÖHs, the national union invites students and their associations to bid for project funding, with special streams for feminist and queer research projects, a stream for activities organised by student dormitory reps, funds allocated for widening access work and one strand for climate-friendly initiatives.

It’s a culture that takes work off the desk of busy student leaders or what would otherwise be expensive staff teams – but enables those leaders to deliver on manifestos through the talent of students.

Its national advice work is impressive too – here to take some load off local unions, the national body offers training and webinars on social issues like family allowances and studying with children, legal advice covering study law, tuition, and examination regulations, and advice on transfer processes between universities. There’s also housing law advice, support against discrimination and accessibility advocacy work for disabled students.

The interaction between that advice work and preventative policy work is deep. An ÖH survey on sexual violence at Austrian universities last year revealed that 10 per cent of students experienced it in a year, with over 80 per cent of incidents unreported, and most victims who did expressing dissatisfaction with the support received. ÖH is now campaigning hard for awareness training for staff, better protection and support for victims, and guidelines to combat sexualized violence at universities.