As someone with a long involvement with the TEF, yesterday was something of a new experience. For the first time, I was among the many on the outside, waiting with bated breath to see what information would be published by the Department for Education and the Office for Students.

It’s quite a different feeling from being on the inside, wondering what the sector will make of the decisions you’ve agonised over and the documents you’ve crafted so painstakingly. But the shock of transition was eased somewhat by the eminent good sense underlying yesterday’s release.

Burden reduction

The two biggest announcements were the shift to a new model, in which all subjects are assessed fully, and the removal of teaching intensity from the TEF. Both are clearly good decisions. Whilst the intention to reduce burden was a worthy one, the evidence from the pilots shows clearly that neither model A nor model B could deliver robust assessments. In model A, in particular, analysis of “non-exceptions showed that 40% would have ended up with a higher or lower rating than the provider rating had they undergone assessment”. Given the importance of accurate subject information to informing student choice, the additional robustness generated by the fuller assessment is clearly necessary.

At the same time, this increase in burden is balanced by the removal of teaching intensity from the TEF, a move supported by 76% of respondents. I am an unabashed champion of the importance of a sufficient quantity of contact time in teaching. But the TEF is not the place to look at this, not just due to the burden of data collection, but because it dilutes the focus on outcomes.

Further changes

Alongside these major changes, the documents contain a host of smaller refinements to the methodology. The core features are, rightly, unchanged including the balance between metrics and qualitative assessment, the focus on outcomes and the importance of both benchmarked data and absolute values.

Beneath this, though, lie a host of improvements:

- The two new NSS scales are both valuable, in particular the consideration of resources, which has been consistently raised by students as important. The decision to include these, while maintaining the overall balance of metrics in which NSS contributes one third of the total score, is helpful

- The decision to instate Longitudinal Educational Outcomes as a core metric, now that it is no longer experimental, and to lose the metric from Destinations of Leavers from Higher Education (DLHE) that simply reported whether or not a graduate was in employment, whilst retaining the more useful Highly Skilled Employment DLHE metric

- The measured approach to keeping grade inflation. Despite overly excitable write-ups in the media, the actual proposals are to retain this at provider level and to supplement it by information on prior attainment

- The thoughtful, technical and considered approach to dealing with the difficult issue of subjects with insufficient metrics

- The proposal that panels should be allowed to award “no Award” when they consider there is insufficient data to reach a conclusion

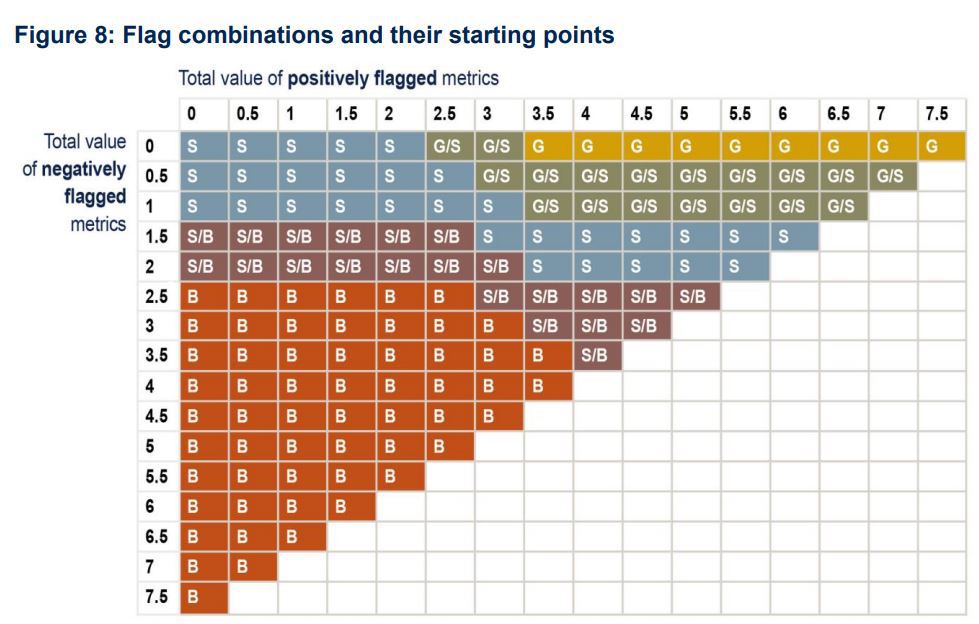

- The improvements to the initial hypothesis calculation to explicitly recognise borderline hypotheses in the guidance, beautifully illustrated by the graph below (Figure 8 in the TEF Subject Level Pilot Guide), which should bring joy to any TEF aficionado.

Down the road

Importantly, for the first time we have a clear understanding of the roadmap to full implementation of subject-level TEF. The decision to go for a big bang approach, in which all providers will receive subject awards in 2021, is by far the best outcome for students, as it will avoid the confusing scenario in which subject ratings are drip-fed out over three years. With most providers getting a bonus year on their existing rating, there should be few complaints from that front, also.

There are a few small areas that remain of concern that will need to be addressed in the second year of the pilots.

Yesterday’s documents do not describe how the TEF will transition from DLHE to Graduate Outcomes, an important consideration in maintaining consistency over the years.

The proposed new metric on differential outcomes, while addressing an important issue, carries significant risks, both in terms of the very small sample sizes involved and, more seriously, due to the risk that it may perversely incentivise providers to play safe when deciding whether to admit applicants from non-traditional backgrounds. While it is reasonable to pilot a metric it may well be that, like teaching intensity, this important issue is best addressed outside the TEF.

And finally, while necessary, the new model nevertheless carries challenges in ensuring the burden remains proportionate – a clear argument in favour of moving to a six-year rather than a four-year assessment cycle.

All these, however, are eminently solvable challenges, and do not compromise the robustness of the overall approach.

In conclusion, Sam Gyimah has demonstrated that he is taking a pragmatic, sensible and evidence-based approach to TEF, focusing on the essential elements and learning from the pilots to ensure the process remains robust. That this is being achieved without compromising on the TEF’s core objective of driving up quality, focusing on outcomes and delivering better information to students bodes well for the final roll out in 2020-21.

I’m sorry- this still seems like an overcomplicated mess. I doubt the TEF will have a long life- unwieldy systems that don’t benefit the institutions they assess rarely do.