It was another early train from King’s Cross, boarding in the dark, then watching the dawn unfold reluctantly around Grantham’s lone spire.

Arriving into York, it was most definitely January; cold, grey and wet.

Not even the sight of ye olde city walls, or some of the hundreds of cosy pubs, could cheer up the cycle to the University of York campus, just east of town.

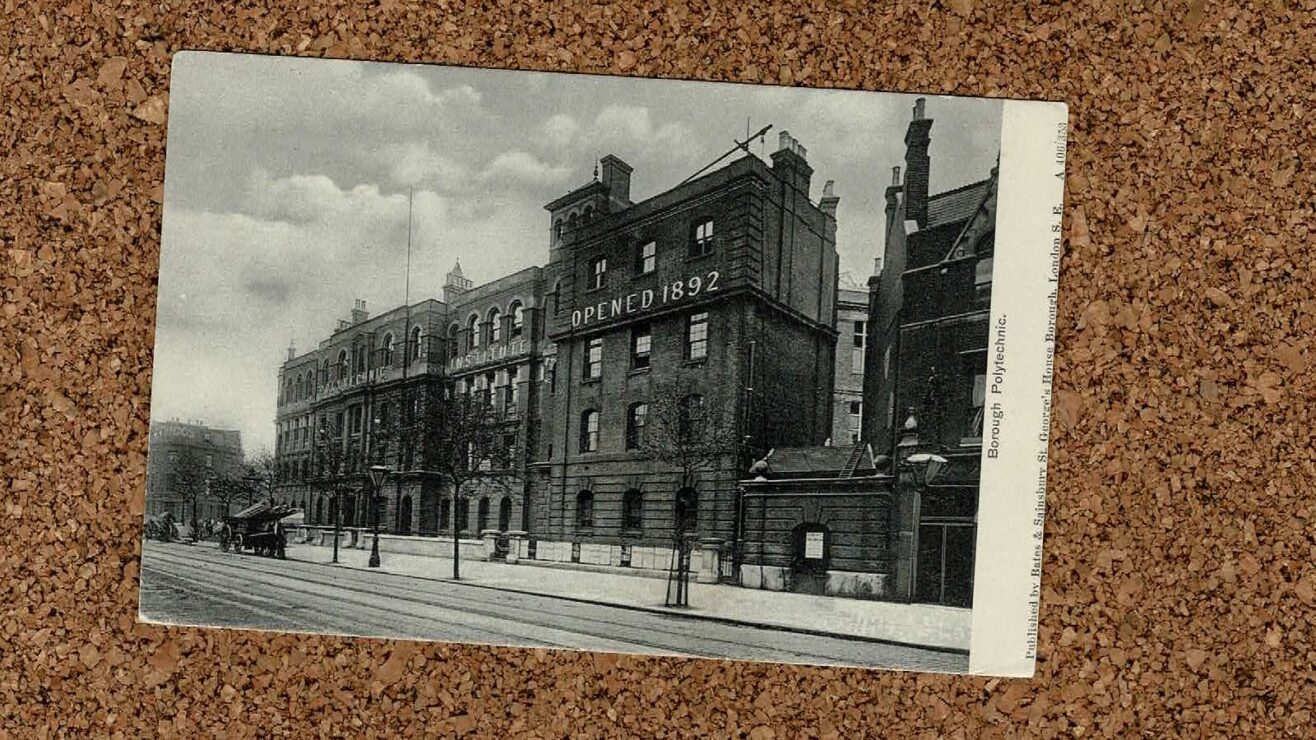

But it was good to be back, 14 years after graduation. At the heart of the campus is Heslington Hall, a typical Elizabethan country house, used by 4 Group Bomber Command during the Second World War. Its grounds became the original 1960’s campus, gathered around its iconic lake, ‘spaceship’ central hall, and the raft of miscellaneous waterfowl.

Head of Media Relations, Alistair Keely, led the tour, starting with the original campus.

Some of it was achingly familiar, with pebble-dashed concrete and helpfully covered walkways, but there were many new buildings too. One of York’s crown jewels is the biology department, performing strongly on national and international measures for research, teaching and funding.

Its mostly-new cluster of buildings hosts about 200 staff, 350 postgrads, and 800 undergrads. We kept stumbling across the latter, tucked away in corners, cramming for the upcoming exams that are always so cruelly timed just after the Christmas break.

The labs were the biggest I’d ever seen, three have 120 stations.

We then proceeded to explore the new half of the university, Campus East, entirely constructed in the last ten years. Clearly knowing his audience, this was conducted by bike, but the cycle tour became increasingly epic as the weather worsened and we passed through ongoing construction sites, with their attendant mud.

We visited the new Department of Theatre, Film and Television, complete with state-of-the-art post-production facilities, hired out by blockbuster films and TV shows such as Mad To Be Normal, starring David Tennant and Elisabeth Moss.

The new campus and departments seemed indicative of a quiet success story, with strong growth in domestic and international students, as well as research funding and outcomes. But Keely explained that it was sometimes hard to “help busy colleagues tell their story”, and for them to see the benefits of doing so.

He also sang the praises of the York Futures employability programme, which tries to equip students for the next stage, building on the excellent York Award, which still influences how I give presentations today i.e. without a script.

Talking research

Fleeing the sideways rain, and one costume change later, I was chairing a session at York Talks, the university’s annual research showcase, which brings academics together across disciplines and helps the public to understand their research. In front of a packed and diverse audience from across the university and beyond, four impressive academics had just 15 minutes to sum up their latest research and a career’s worth of expertise. Use of big data in farming, voice recognition, facial recognition, and the terrifying world of combat drones, all got explained and challenged by the audience. It was fascinating stuff and a good reminder that these ‘out-of-touch elites’ are actually at the cutting edge.

I then met Damian Murphy, an Audio and Music Technology expert, and one of seven ‘research champions’ – aligned to the university’s cross-cutting themes. His theme is creativity and he talked of its importance to “the industrial strategy, to knowledge exchange, and to the local ecosystem of creative-industry startups and freelancers”, one of the “emergent sectors” in North Yorkshire. The new Theatre, Film and Television department is already getting used by businesses in this sector, working with Screen Yorkshire and the cross-disciplinary and part-government funded DC Labs.

We also talked about the flyer I’d been handed earlier in the day, by The White Rose University Consortium – a partnership with the universities of Leeds and Sheffield – which has set up as a new university press as an open access digital publisher, a great example of building modern and efficient shared research infrastructure.

Next, I got to meet Koen Lamberts, the vice chancellor, a psychologist from Belgium. He stressed that York sees itself as “a global university first and foremost”, but that doesn’t mean it can’t engage at national, regional and local levels too. In fact, Lamberts saw this as essential in order to maintain and build broad public support.

He also said ”as the university starts its next five-year strategy, above all what it needs, is stability”, in terms of policy and funding. There have been “massive changes” recently, and they have “knock-on effects internally”. Universities can and do adapt, but it takes time if it’s to be done properly. Short-term and sudden changes, such as the fee freeze, hit finances with little warning, and can “only be survived for a couple of years” before they have a significant impact.

He pointed out that with OfS we now have a market regulator, but that it’s “rather a dysfunctional market”. Higher education is not a consumer product, the ‘value’ created for the money spent on it isn’t easy to understand and explain. What do we mean by value, and for whom?

He also talked about “stability and coherence” in the industrial strategy. How might UKRI and the Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP), where Lamberts sits on the board, best work with them on a devolution or city deal? They’re already involved in the Northern Powerhouse, but different policies don’t always make it clear how an institution such as the University of York should best engage, especially given limited resources and wider uncertainties.

I learn that Lamberts also chairs the N8 Research Partnership, a collaboration of the eight most research-intensive universities in the North.

On those wider uncertainties, Brexit obviously came up, creating challenges for students, staff, funding, and the range of international partners the university works with.

York is also very much a research-intensive university. Lamberts said that “providing it’s appropriately benchmarked, KEF should be a useful rather than a threatening development”, building on HE-BCI survey data. But all of these frameworks have to be thought through, to “properly” account for the sector’s diversity, and the incentives created.

Within the university, Lamberts talks about stimulating links between researchers and beyond the university, by “breaking down entrenched historic barriers”. Departments and disciplines have been reorganised into a three-dimensional matrix structure, across the seven university research themes. I imagine he’s quite good at solving a Rubik’s cube.

Table talk

The day finished with the customary drinks reception and dinner, in Heslington Hall. I was honoured to be among the VIPs and by most measures it was a fancy setting, but somehow came across as more modest and understated than many institutions I’ve visited. There were strip lights rather than candles, and buffet service rather than high table. The board and senior managers I met seemed quietly pragmatic, rather than bombastic.

Over dinner, my neighbours again reminded me about some of the fascinating things that happen at universities. I learned, for example, how augmented-reality cultural installations can help tourists rediscover Egyptian pyramids, whilst also helping poor communities nearby to engage.

I also learned about some of the day-to-day realities of being an academic in a modern university. It sounds tough. Although to me York seems successful, others thought it less commercial and less monied than some of its peers. The growth and the successes are also accompanied by change and some pain. I wonder if ministers really understand what impact their policies have on people’s lives?

I’ll be back up int’ North on 8th June, to chair a session at the university’s other annual public showcase, the York Festival of Ideas, this time on the future of universities. It feels like a pretty timely topic.

Wow – what an insightful article!