Finally, a politician who gets it. Not that one

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

But buried in the wonkier parts of the press yesterday was the more interesting news that Torsten Bell is to play a key role in preparing this Autumn’s Budget – with an eye on growth.

The former boss of the Resolution Foundation and current MP for Swansea West became pensions minister and parliamentary secretary to the Treasury back in January, and has been described by a Rachel Reeves ally as one of Labour’s “sharpest minds” and as someone who has:

…seen the Budget from both ends – in the room helping to write them and on the Today programme dissecting them.

Bell was first in the Treasury in his mid-20s as a special adviser to Alistair Darling during the 2008 financial crisis – before serving as Labour’s director of policy during Ed Miliband’s leadership. Notwithstanding disasters like the “Ed Stone” and the 2015 election pledge to cut fees to £6,000, Bell is at least someone who appears to “get” both student loans and the role that universities and graduates can play in growth.

On the former, for example, Bell has been one of the few players to notice not just headline fees and repayment rates, but the distributional realities beneath them. When he appeared before MPs at the Treasury Committee in 2022, he noted that “Plan 5” – with its interest rate cut (to RPI) and repayment period of 40 years, would mean:

…overall, an increase in how much graduates are paying … it is really bad news for women and much better news for men.

Career breaks, lower lifetime earnings and regional disparities mean that a chunk of costs have been shunted onto the groups already struggling.

He has also been pretty forthright about the intergenerational consequences. When the reforms were announced, Bell warned:

…we’re protecting the wealth of the old while stuffing the earnings of the young. What kind of country do we want to be?

In an era where the distribution of wealth across generations is already fracturing Britain’s social contract, the framing invites a bigger debate about whether loading more of the cost onto the young is economically rational – or politically sustainable.

Bell was also keen to point out that the changes reduced the government’s measured borrowing because a higher share of the total cost is shifted from taxpayers to students, lowering the up-front write-off recorded in the public finances. And The Resolution Foundation is one of the few organisations to have noticed that tuition fee loans count as “income” in government household surveys, artificially inflating student living standards:

…cutting tuition fees would – given how these things are currently measured – appear to cut household income growth and increase poverty.

We’re used to debates about both the long-term split between taxpayer and graduate, and the distributional impacts of tweaks to student loan terms on different lifetime earnings profiles – but given the government borrows the money it lends to students (both in England in the devolved nations), Bell has something else to handle too.

A new £14bn black hole

When the Department for Education works out the cost of the loan system to the public, its Resource Accounting and Budgeting (RAB) calculation is backward-looking and slow to adjust, all while ONS’ accounting treatment doesn’t include the cost of government borrowing at all. The extra billions involved do end up in the government’s accounts – but as higher general debt-interest spending rather than against the student loans line. That means the “true” cost is under-recognised in the statistics that ministers usually cite.

But the political difficulty is obvious. As things stand, the Treasury is effectively subsidising even those loans that are repaid in full, because the government is borrowing at rates much higher than those it is lending. That subsidy grows if graduate wage growth softens and repayment prospects deteriorate. But raising student loan interest rates to close the gap is toxic, and pushing up the RAB charge risks crowding out other education spending.

So if it was the case that pre-election, Bridget Phillipson thought that putting 1 per cent back on interest rates might free up some upfront to spend on maintenance, the Treasury are now likely to want the dividends. And of course, this impacts all four loan systems because all four are financed in the same basic way by HMT.

Back in January 2024, the IFS noted that covering the cost of student loans is getting very expensive – and if you’ve seen headlines in recent weeks, you’ll know that’s all been getting worse. As I type, the cost of government borrowing as measured by the 15-year gilt yield has risen from 1.2 per cent to 5.1 per cent over the past three and a half years.

Relative to expected RPI inflation, that’s a 4.1 percentage point increase. And as the interest rate on student loans is now the rate of RPI inflation, this means that the government can expect to pay around 2.7 percentage points more in interest on its debt than the interest rate it charges on student loans. Ahead of the most recent student loans reform, it could expect to pay 1.4 percentage points less than the rate of RPI inflation.

In that January 2024 report, the IFS estimated that the rise in gilt rates had added around £10bn to the government’s “real” RAB charge – a simple linear scaling since then suggests an extra £4.1bn on top of the IFS figure. That would take the total in-year cash requirement for forecast non-repayment to around £14bn rather than £10bn – before anyone even thinks about increasing funding for students or universities.

More graduates please. Just not that sort and not there

The more reassuring news is Bell (and colleagues’) views on HE spending and its role in growth. In Stagnation Nation, he argues that if Britain wants to close its growth gap with comparable economies, it needs more graduates – but that simply increasing participation without thinking about what students study, where they study, and how their skills are used is not enough:

…the problem is not that we have too many graduates, but that we do not make enough of them, and we fail to use them effectively.”

He highlights the way other advanced economies have invested in their higher education systems to boost both the supply of graduates and the relevance of their skills. By contrast, the UK has been coasting on a 1990s and 2000s expansion that widened access, but has since relied on a funding model that leaves students facing high debts, universities locked into financial precarity, and policymakers distracted by headline fee levels rather than outcomes.

In the book, the danger is obvious – if participation growth stalls, if regional universities struggle to attract and retain talent, and if graduates are funnelled into roles that don’t use their skills, the country risks entrenching low productivity and weak wage growth.

That’s why it frames higher education not just as an individual opportunity but as a collective growth strategy. Crucially, the book notes that in countries where graduate supply has risen fastest, so too has demand – because governments and employers have invested to ensure those graduates could be absorbed into high-value industries. The UK, it argues, has been complacent on that front, allowing underemployment and regional mismatch to waste the potential of thousands of young people.

The emphasis on “just not there and studying that” also matters in regional terms. It points out that while London and the South East benefit disproportionately from graduate density, much of the country remains under-supplied.

Regional universities play a vital role in training teachers, nurses, engineers, and public service professionals – but they are precisely the institutions under the greatest financial strain. Left unaddressed, that creates a vicious circle – fewer opportunities for young people outside the South East, less local graduate retention, weaker regional economies, and, ultimately, even greater inequality.

A growth strategy that ignores those dynamics is:

…a growth strategy doomed to fail.

And then there is the question of subjects. The book is clear that Britain’s skills deficit is not evenly spread. We produce world-class research and a healthy supply of graduates in some fields, but we are chronically short in others – particularly technical and applied areas that underpin productivity.

That is not an argument to downgrade the arts, humanities, or social sciences, but a recognition that simply expanding numbers without a sharper strategy risks more mismatches. The challenge, as the book frames it, is to have a funding and regulatory system capable of incentivising the right mix without destroying institutional autonomy or student choice.

That’s a political tightrope, but one he suggests cannot be avoided. And given what we’ve been seeing over the past two years, the choice now may need to lean more toward controls and caps than mere incentivisation.

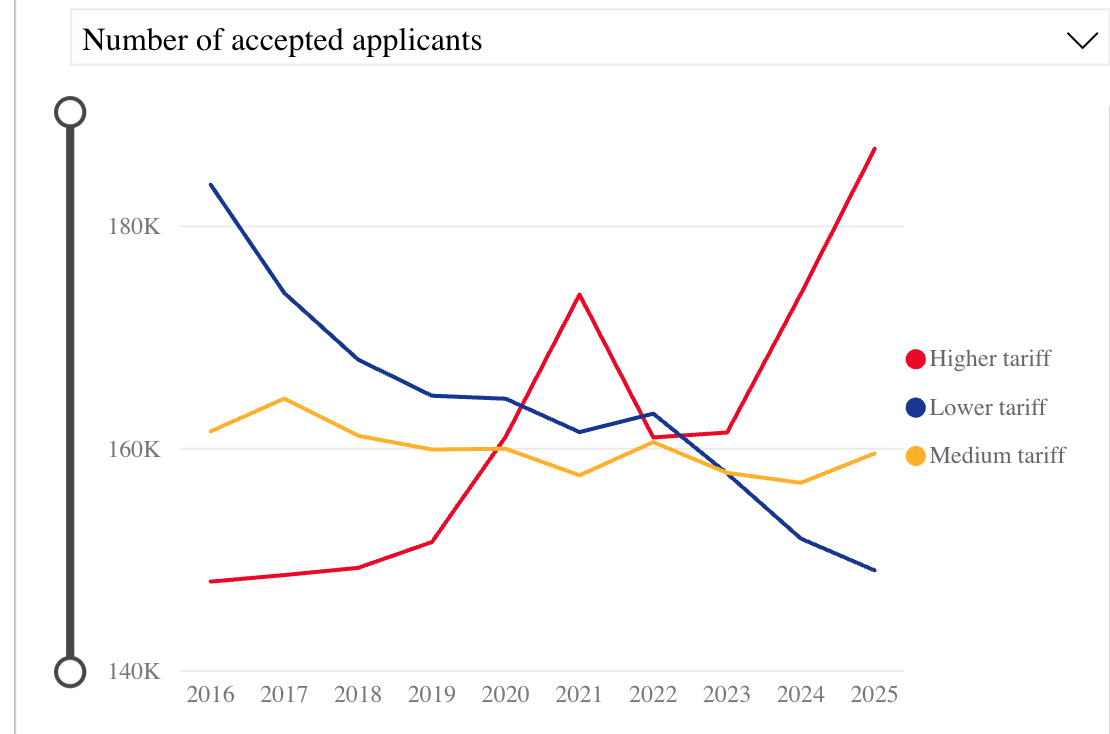

(UCAS daily Clearing analysis 2025, 12 days after Level 3 results day)

Maintenance plays a role too – the Lifelong Loan Entitlement is all well and good, but the book argues that the student support system surrounding it has flaws that will be “particularly off-putting” to the young people it needs to attract, with the share of families eligible for the full level of maintenance loan support coming in for particular criticism, as well as the silence on means-tested maintenance grants for those studying a first Level 4 and 5 qualification.

Crucially, it argues that the objective should not be to make existing universities ever larger, but instead:

…innovation in provision with new forms of sub-degree provision are required, just as we need new institutions able to serve so-called “cold-spots” that lack a university such as in Blackpool and Hartlepool, building on recent successes in Lincoln, Chester and Worcester.

Taken together, the arguments paint a picture that will resonate in the Treasury. For Bell, the UK’s economic stagnation is not an accident but a consequence of policy failure. Higher education sits right at the intersection of those failures – underinvestment, incoherent strategy, and political short-termism.

The prize of getting it right – more graduates, spread more evenly across the country, trained in disciplines that drive productivity – is not just higher growth but stronger social cohesion. If Bell brings that perspective into Budget planning, higher education funding may stop being treated as a fiscal liability to be contained and start being seen as an investment in breaking Britain’s stagnation.

As you put his argument, there is not much to disagree with here. In Bell’s model, aligning skills to economic growth is complicated by a few things. Identifying the industries with potential for economic growth is the crucial intermediate factor between skills and economic growth. What is economic growth? Higher output prices at scale plus investment for cost savings. Matching short-term and long-term economic growth measures? A traditional model would include physical factor endowments, but we are a service economy, vulnerable to security of supply in so many physical imports. The scale of home country demand is the launchpad for… Read more »