It’s not just in the UK – the student housing crisis has reached critical levels right across Europe.

Last year, there was a shortage of 3 million beds for students across Europe and the situation is expected to worsen in the next five years, when there will be a need for an additional 200,000 more beds, according to a 2024 analysis by global real estate firm JLL.

This is in part because Europe’s student population is expected to grow by 10 per cent by 2030/31, reaching 23.5 million – with half being international students, according to an ICEF Monitor report.

Europe’s top student cities face the biggest housing shortages, with 40 cities making up 40 per cent of the 3-million-bed deficit.

Construction costs for traditional student accommodation have soared to unprecedented levels, with new builds averaging £126,866 per bed in conventional halls. Meanwhile, students face average monthly rents of €895, with many spending over 50 per cent of their budgets on housing alone.

In the UK in many cities €895 would be a bargain – and in England, some are predicting a real crunch coming if landlords of off-street housing sell up as a result of the Renter’s Rights Bill.

Around the world, universities report waiting lists stretching for years, international students sleeping in tents, and enrollment growth far outpacing housing capacity. In cities like Dublin, Amsterdam, and London, where land is scarce and construction timelines stretch 18-24 months minimum, rapid solutions are essential for maintaining educational access.

SUs across Europe have been at the forefront of demanding innovative solutions. NUS launched its “Fix Student Housing” campaign, calling for radical changes to how student accommodation is provided and funded. NUS believes housing co-operatives offer democratic alternatives where “tenants own, run and manage their own accommodation”.

And the European Students’ Union (ESU) and Erasmus Student Network conducted surveys revealing the depth of the crisis facing international students, with many unions actively exploring alternative housing models.

Creative alternatives emerging across Europe

The crisis has generated numerous creative solutions across Europe.

In the Netherlands, intergenerational housing programmes match students needing accommodation with elderly residents seeking companionship. Students provide 30 hours of volunteer work monthly – teaching technology skills, organizing activities, or simply providing company – in exchange for free housing. This model addresses both housing shortages and social isolation among elderly populations.

Abandoned churches across Rotterdam and Utrecht have been transformed into spectacular student residences. A former Rotterdam church now houses over 200 rooms across six floors, complete with stained glass windows and soaring ceilings, all for under €500 monthly. They preserve architectural heritage while creating unique living spaces that students actively seek out.

Empty office buildings are another opportunity. In Delft, a building vacant for 10 years now houses 150 students annually. The former Philips headquarters in Eindhoven underwent similar transformation. These conversions typically feature individual rooms, shared facilities, and expansive common areas – often with spectacular city views from upper floors.

Some students work as au pairs, exchanging childcare duties for rent-free accommodation with families. Others participate in experimental sustainable housing projects, like Delft’s wooden studio “laboratories” where students live in cutting-edge sustainable designs while providing feedback to researchers developing future housing solutions.

One of the biggest crises has been seen in Dublin, with students sleeping in cars and dropping out due to lack of accommodation. A few years back SUs launched a “Digs Drive” to proactively recruit homeowners to rent spare rooms to students. It involves mass leafleting in areas near campus and along transport routes, addressing critical issues such as international students needing 7-day lets, ensuring access to kitchen and living spaces, and keeping rents affordable during the cost-of-living crisis.

The band-aid solution has its downsides – including some landlords seeking student labour in exchange for rooms or restricting facilities – but it’s proving more effective than alternatives, attracting media attention, maintaining pressure on government and universities for long-term solutions, and helping students avoid 4-hour daily commutes that force many to consider leaving education altogether.

But elsewhere in Europe, there’s another intriguing solution that could hold the key to at least alleviating the crisis.

The container revolution

In 2005, Amsterdam faced a crisis that threatened its future as a global education hub. Student housing was desperately scarce, rents were skyrocketing beyond student budgets, and waiting lists stretched endlessly. The city’s universities risked losing talented students who simply couldn’t afford to live there.

Then via some active campaigning from ASVA (the city-wide SU which represents all 100,000 students in the city, including those in universities, universities of applied sciences, and vocational education) a company called Tempohousing, a Dutch modular housing company, proposed something unprecedented – transforming 1,034 shipping containers into the world’s largest container student housing complex.

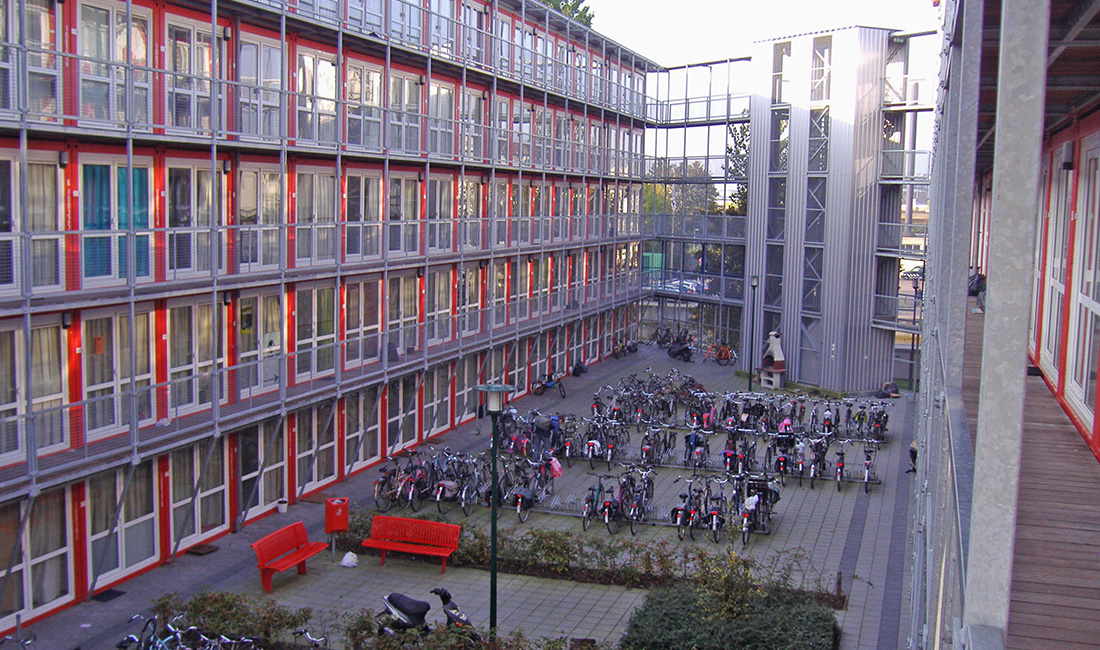

Many were sceptical – would students really want to live in metal boxes? But when Keetwonen opened its doors in late 2005, something astonishing happened. Within months, it became the second most popular student residence in Amsterdam, with waiting lists stretching for years.

Students loved their 28-square-meter private studios complete with bathrooms, kitchens, and balconies. The project, originally planned for just five years, remained operational until 2020 due to overwhelming demand. At €400 per month all-inclusive, it proved that innovative thinking could solve seemingly intractable housing crises.

In the East of the Netherlands, a similar crisis became so acute that in August 2021, the Executive Board at Twente University told students who did not yet have a room to reconsider coming at all – highlighting the desperate state of student accommodation in the city.

But Twente Student Union in Enschede had heard about the Amsterdam innovation and started to campaign for something similar. In February 2022, a complex with 230 flexwoningen (flexible housing units) for students was opened on the UT campus at Witbreuksweg.

The units have a surface area of 28 m², and include their own shower, toilet, kitchen and front door, with students able to rent fully furnished units 100 new student houses on the main campus boulevard – U-Today.

The monthly rent was set at 430 euros per month (excluding service costs), making them an affordable option compared to the traditional student housing market. The units could be placed in relatively short time because infrastructure from 2004-2009 already existed when the land was previously used for temporary student housing.

It came with limitations and mixed responses. The housing is intended primarily as “peak accommodation” where students can live temporarily as a bridge solution, with the units currently permitted to remain until 2029. The allocation system prioritises students based on urgency and current travel distance, with priority given to students currently more than two hours’ travel distance away, though a lottery system is used when demand exceeds supply.

Meanwhile in the north of the country in Groningen there was a growing international student population, so the student associations around the city campaigned to the local council to address the housing shortage. A joint ambition was agreed to find at least 500 and possibly up to 1000 student rooms – and it was container units that formed a big part of the strategy.

The units, now known as Sugar Homes (the land was the former home of the Suikerunie sugar factory) offered fully independent studio apartments of approximately 27 m² (289 ft²), fully furnished with private kitchen, bathroom, and shower.

How shipping containers become student homes

The transformation from cargo container to comfortable student accommodation involves a sophisticated technical process that maintains structural integrity while creating livable spaces.

It all starts with selecting appropriate containers, typically 40-foot high-cube units providing 9.5 feet of interior height. They undergo extensive modifications, creating openings for windows and doors, and structural reinforcement added around each opening to maintain the container’s load-bearing capacity.

They incorporate complete utility systems – electrical wiring following standard building codes, plumbing with efficient tankless water heaters, and systems designed for the thermal properties of steel construction. Each unit gets safety features like smoke detection systems, emergency exit windows meeting building regulations, and fire-resistant materials throughout.

It’s pretty efficient because while sites are being prepared with appropriate foundations, containers are simultaneously being converted in factories. That allows for weather-independent construction and quality control impossible with traditional building methods.

The result is a fully equipped living space delivered to site ready for connection to utilities, massively reducing on-site construction time and disruption.

Financial advantages that demand attention

If you were advocating this to the university, you’d need to know about some of the numbers. Economics. Fisk University’s 2023 project delivered 98 student beds for $4 million, achieving a per-bed cost of $40,816 – compared to traditional halls construction averaging $126,866 per bed. This 40 per cent cost reduction isn’t an outlier – the College of Idaho reported their container housing cost “two-thirds the price” of conventional construction.

The savings stem from multiple factors. Construction timelines compress from the typical 12-24 months for traditional buildings to just 3-6 months for container projects. That means institutions can respond to student numbers surges without multi-year planning cycles, and students can access accommodation faster. The modular nature of it enables phased development, allowing universities to add capacity incrementally rather than committing to massive upfront investments.

The financial model differs significantly from traditional student accommodation. Container units typically cost between £25,000-£60,000 per unit (depending on specs), compared to £100,000-£150,000+ for conventional PBSA (Purpose Built Student Accommodation). Many providers budget on an 8-year replacement cycle, treating containers as depreciating assets rather than permanent buildings. That creates an annualized cost structure of approximately £7,500 per bed per year, including depreciation, maintenance, and reserves for replacement – still a lot lower than traditional models despite the shorter lifespan.

Operating costs also favour container housing. Standardised units simplify maintenance procedures and reduce costs. Energy-efficient designs, despite the thermal challenges of steel construction, often achieve comparable or better performance than aging traditional halls. And the smaller footprint of individual units – typically 160-320 square feet – reduces heating and cooling demands.

For SUs advocating for affordable housing, the rental price advantages are significant – container housing projects consistently achieve lower rents. Keetwonen maintained €400 monthly rents over its 15-year operation, while Urban Rigger in Copenhagen offers waterfront studios for €450-600 in one of Europe’s most expensive cities.

SU perspectives and campaigns

Student organisations have been key in pushing for container housing. At Fisk University, student government consultations through town halls and surveys showed overwhelming support, with the uni’s Executive Vice President Jens Frederiksen reporting:

“They all wanted to live in these shipping containers.

Container housing addresses student environmental concerns that increasingly influence student decisions and campaigns. Each repurposed shipping container diverts approximately 3,500 kilograms of steel from waste streams, reducing demand for virgin materials. Life cycle assessments show that container housing can achieve 34 per cent lower CO2 emissions compared to conventional buildings, with factory-built modules producing up to 45 per cent less carbon emissions than traditional on-site construction.

Students, as Fisk University discovered through surveys and town halls, actively embrace “innovation, sustainability, thoughtful living, and micro-living.” The visible repurposing of industrial materials into living spaces creates a connection to circular economy principles that resonates with environmentally conscious students. Projects like Urban Rigger integrate solar panels and hydro-based heat exchange systems, achieving carbon neutrality while floating on Copenhagen’s harbor.

Speed of deployment is another big advantage for SU campaigning. With traditional construction timelines stretching 12-24 months minimum, container housing’s 3-6 month delivery enables rapid response to housing crises. Keetwonen’s construction achieved 150 completed homes per month, a pace impossible with conventional methods. That kind of rapid deployment particularly benefits universities facing sudden student numbers growth or emergency housing needs.

European success stories

If you were advocating this to the university, you’d also need to know where it’s working. Beyond Keetwonen’s groundbreaking example, successful implementations across Europe show container housing’s scalability.

Berlin’s Frankie & Johnny project (EBA51) houses 400 students in aesthetically striking blocks that won design awards. Achieving 30 per cent cost savings and 50 per cent faster construction than traditional methods, it offers all-inclusive rents of €389 monthly in one of Europe’s most competitive housing markets.

Urban Rigger in Copenhagen is an evolution in container housing design. Created by famous architect Bjarke Ingels, floating units address land scarcity by utilising harbour space. With monthly rents around €600 and features including rooftop solar arrays and seawater heat exchange systems, the project shows how thoughtful design can transform industrial materials into desirable living spaces.

In the UK, progress has been more limited but significant. Bristol’s Launchpad project, in Jim’s old student town Fishponds, provides affordable accommodation at £523.84 monthly all-inclusive for students, targeting “young people at risk of becoming homeless”. The partnership model shows how container housing can address both student needs and broader social challenges.

Scotland’s True Glasgow West End is the UK’s largest container student housing project to date. Built for £64 million using 500 repurposed units and completed in just 10 months, it offers “upmarket student digs” with modern amenities including an enclosed slide between floors.

Interestingly, while Dublin seriously explored container housing during its 2016-17 housing crisis – with the Higher Education Authority and local councils investigating options for Dublin and Maynooth – no large-scale projects materialised. Regulatory complexity, particularly around fire safety and insulation standards, combined with concerns about the depreciation model, stalled implementation.

Design innovations

If you were advocating this to the university, there would be concerns about “living in boxes” or whatever. But modern container housing bears almost no resemblance to basic metal boxes.

Contemporary designs have got large windows, private balconies, and high-quality finishes that students often prefer to traditional dormitories. Interior layouts maximise space efficiency through built-in furniture, vertical storage solutions, and multi-functional areas. Students report that upon entering well-designed container units, they “forget they’re in a shipping container.”

Community design plays a crucial role in success. Rather than isolated units, successful projects create social spaces. Keetwonen’s courtyard design fostered interaction while preserving privacy. Frankie & Johnny’s central lounge serves as the “heart of the ensemble,” and Urban Rigger’s floating platforms include communal terraces and kayak landings. The design elements address concerns about isolation and create workable living communities.

Technology integration is also a feature. High-speed internet infrastructure, smart home features, and energy monitoring systems appeal to many students. Modern insulation techniques using materials like NASA-developed aerogel provide thermal performance while maximizing interior space in some of the examples. LED lighting, efficient appliances, and renewable energy systems reduce operational costs while supporting sustainability goals.

More yebbuts

So are there downsides? The most significant challenge involves overcoming initial stigma. As Blake Cowman, College of Idaho’s Student Body President, admitted:

You hear ‘shipping container housing’ and you kind of pull back a little bit.

The perception issue requires proactive communication emphasising quality, amenities, and actual student experiences.

Acoustic issues represent another concern – metal structures can transmit sound between units, necessitating specialised soundproofing that adds cost and complexity. Planning regulations and “tolerance” vary significantly between areas, and often lack specific provision for container construction, which can delay approvals and increase costs.

The 8-year replacement cycle raises questions about long-term sustainability and financial planning. Universities have to budget for complete unit replacement rather than renovation, creating different financial dynamics than traditional buildings. The depreciation model, while transparent, requires some discipline in maintaining replacement reserves and may complicate financing arrangements – although in some cases it simplifies things too.

Health and safety concerns need proper attention. Containers used for international shipping can contain pesticide residues or toxic fumigants requiring careful remediation. Fire safety modifications have to meet strict building regs, including adequate exit routes and fire-resistant materials. Proper ventilation systems are also essential to prevent condensation and ensure healthy indoor air quality.

Strategic implementation recommendations

If you’re an SU considering container housing campaigning, success needs a strategic approach and stakeholder engagement. You’ll want to start by documenting your uni’s specific housing crisis – student growth outpacing capacity, affordability challenges forcing students miles away, or ageing facilities requiring expensive renovations. Quantifying the impact on student success, retention rates or mental health is going to help.

You might want to partner with sustainability-focused societies who can champion environmental benefits. Working with university staff to identify suitable sites and funding mechanisms, whether institutional investment, public-private partnerships, or developer-led models also will matter.

As student representatives at Fisk University concluded after their initial skepticism transformed into enthusiasm, container housing can be “a slam dunk” for universities willing to embrace innovation. The question for SUs isn’t whether alternative housing solutions can work – examples across Europe prove they can – but whether your uni is ready to think outside the box (or, rather, inside the box) to solve your housing crisis.

Read more

What is the rest of Europe doing about student housing?

Could SU “digs drives” be a short-term solution to an intensifying student housing problem?

Keetwonen Amsterdam (Tempohousing)

Bristol Launchpad (Bristol University)

EBA51 Berlin (Frankie & Johnny)

Is shipping container student housing gaining traction in the U.S.?

Turning shipping containers into dorm rooms” (Inside Higher Ed)