A long time ago, in a land far, far away from where I sit in Swansea, King Kumaragupta I established a monastery as a centre for higher learning. The monastery was in Nalanda, in modern-day India, and the year was something like 427 CE.

Nalanda was already a holy site: it had been visited by Siddhartha Gautama – who you might know better as Buddha – and was the birthplace of one of his disciples. By 427 CE there had for some 700 years been a stupa at the site, containing the remains of Sariputta, the disciple. Mahavira, a significant character in Jainism, had lived there. It was a place of pilgrimage.

Roy Lowe and Yoshihito Yasuhara’s 2016 work, The origins of higher learning, contains a good discussion on Nalanda, on which this blog draws. The monastery was active between 427 and the twelfth century CE, so it had about 700 years of existence, and overlapped the creation of the first European universities and the Islamic centre of learning based upon mosques and libraries.

Nalanda attracted scholars from many countries and regions – Lowe and Yasuhara report Persia, Tibet, Chia, Korea, Indonesia and Mongolia. (Their book highlights just how mobile scholars – and their ideas – were in the ancient world. It’s well worth a read.) From two of the Chinese scholars, Hiuen Tsang (who spent three years at Nalanda) and I Tsing (who, emulating Hiuen Tsang, spent ten years there), we can find out about life and learning at Nalanda.

It seems that Nalanda was organised on a collegiate basis – that is, residential, with tutors supervising students’ learning. At its height there were about 1,500 tutors and 8,000 students, which is a very Oxbridge ratio.

To gain admission, a student had to answers questions posed by the gatekeeper; apparently only one third of those who sought entry were successful. A high degree of literacy was expected of applicants: they must be familiar with core Buddhist texts and philosophical writings, although there was no religious belief bar to study.

Kumara Gupta I and subsequent rules had granted Nalanda a substantial income, from the produce of over 200 villages. This income supported the tutors and scholars: there were no tuition fees, and no requirement for students to undertake any task other than learning, discussion and contemplation.

The site was about the size of the City of London; there were ten temples, eight monastic buildings – which served as colleges – and over 600 individual study-bedrooms. But don’t think modern rooms with ensuite – this means space for a bed, and niches in the walls for a light and a bookshelf. The library was in three buildings, one of which was nine stories high; it is estimated that it held several hundred thousand texts; and copies were given to scholars who left for elsewhere.

Nalanda was governed by an assembly which took all major decisions, including those relating to admission, allocation of study-bedrooms, and students discipline. (Nalanda’s authority over its members seems to have been like that of a medieval European university.) There was a clepsydra, which regulated the times for eating and bathing.

The curriculum is known to have included study of Buddhist texts, and other subjects such as medicine and magic. Amartya Sen identified the subjects as including “medicine, public health, architecture, sculpture and astronomy… religion, literature, law and linguistics.” It is clear that Nalanda was a site for secular learning, not simply religious instruction. There was a tall tower for astronomy.

And, wonderfully, it seems that Nalanda spawned other institutions of higher learning. Gopala, who came to power in the region in the 700s, after a century in which there had been a power vacuum and much strife, founded several institutions which formed, with Nalanda, a network. These were at Odantapura, Vikramshila, Somapura and Jaggadala. Lowe and Yasuhara speculate that this could be thought of as a federal organisation: tutors and scholars were able, and indeed were encouraged, to move freely between them; it was a single project to enhance learning.

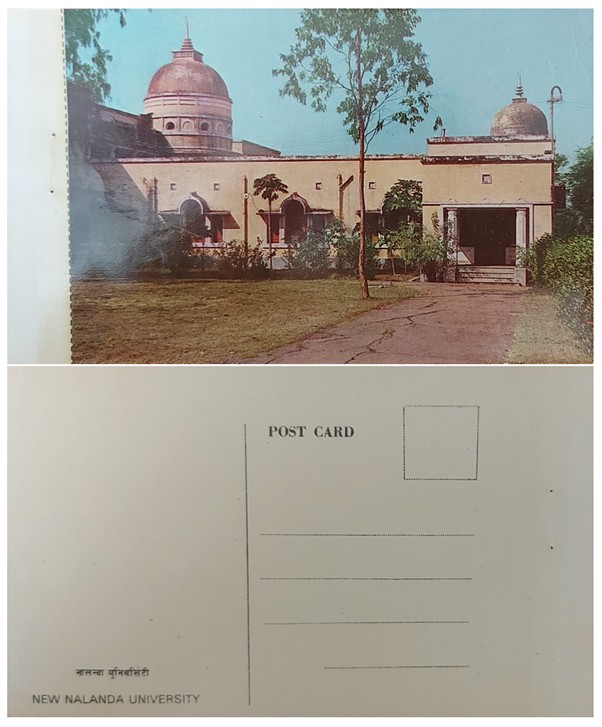

Nalanda is now simply ruins, although a modern university was established near the site in 2010, and in the 1960s there was what was regarded as a new university on the site. It says so on a postcard, which, as we know, never lie.

Here’s a jigsaw of the postcard, which is from a 1960s tourist pack of several of the site and the temple. It is unsent, and the pack had been held together by a rusty staple whose disintegration enabled me to scan this one without damaging the others.