Jacqui Smith rules out (much) more money while her department assesses the impacts

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

DK has summarised that elsewhere on the site – but notably on the responding panel, there was an appearance from his (eleventh) successor Jacqui Smith.

Much of the minister’s material we had heard before – largely reiterating the content of her boss Bridget Phillipson’s letter to the sector back in November.

Willetts (both in his paper and in the presentation) didn’t have much to say about the balance of contribution between state and graduate – so arguably the novel part in the minister’s response was a clear signal that there won’t be extra money coming:

These are difficult times for government finances, and there won’t be a large injection of public money. Therefore, there will need to be strong sector collaboration and much more effective spending.

You wouldn’t expect the minister to offering wads of cash in public, and nor would you expect her to be revealing what the department might or might not be arguing for in the spending review, in case it doesn’t get it – but this sounded a lot more like a message of intent than it did managing expectations:

It is not in the current financial situation likely to be, and will not be the case, that there will be a sort of enormous transferring of the funding of higher education from the current student contribution system to a taxpayer funded system – and so I can travel around as many European countries as I like, but the reality remains the fiscal inheritance that we have as a government, and that will be the starting point on which we’ll be developing our reforms.

The obvious question that that begs – but was not asked – is whether that “the envelope ain’t gonna grow (much)” position means outlay or eventual return to HMT. As we’ve noted on here before, the last government’s reforms delivered a substantial lifetime contribution cut to better earnings graduates by removing interest on loans above inflation – in theory you could increase the “in pocket” resource to both students and universities by easing off on that a little, if Rachel Reeves will allow it.

The other question it begs is on protections for students whose courses get cut while they’re on them – sometimes in ways that are close to, if not over the line on, unlawful. DfE ministers say very little about student protection these days.

Neither Willetts nor Smith were pressed on the twin bits of problematic fiscal drag built into the system as it stands either – one will soon see a single-parent family on the minimum wage being expected to make a parental contribution to the maintenance loan, and the other will see, as of this April, a graduate on the minimum wage starting to pay back their loan immediately. Neither are anything close to where we were a decade ago, mainly thanks to minimum wage increases.

Questions on “over-education” and provider diversity came and went; a question on “regulatory burden” got a refreshing “I don’t believe that it’s regulatory burden that is causing the financial problems within the HE sector”; and a question that (almost) focussed on removing funding for level seven apprenticeships got an answer about putting the savings “to the service of supporting young people who where we’ve seen an enormous fall off in apprenticeship starts”.

There is a need, said the minister, to make sure that the Lifelong Learning Entitlement does enable more people throughout life to be able to benefit from higher education (not that the LLE as currently imagined will cover Level 7) – any further potential questions on the loans for PGT or the apparently declining participation rates were left unanswered.

And the question of whether the government might “bail out” a failing provider got the usual response too – save that Smith argued that:

…in the financing system of HE but particularly in the governance of HE, those autonomous organizations, in order to ensure that they can continue to be they can continue to be successful… may need to organize themselves differently.

Again, the question of impacts on continuing students of that “organising differently” thing didn’t come up. And more generally, the question of whether quality might suffer on a much lower (real terms) unit of resource than that introduced by Willetts – and any potential conflicts between efficiency on the one hand, and provider and subject (geographical) diversity on the other, went unexplored too.

PG fees and DSA

Separately today, a statement from Bridget Phillipson to the Commons (which has also been replicated by Jacqui Smith in the Lords) confirmed the “package of measures to support students and stabilise the university sector” – that’s the tuition fee rise and the (maximum) maintenance loan rise – with some remaining detail added in. The usual accompanying statutory instrument is out too.

No surprises here – maximum disabled students’ allowance in 2025/26 will increase by the same 3.1 per cent, maximum grants for students with child or adult dependants who are attending full-time undergraduate courses will also increase by 3.1 per cent, and maximum loans for students starting master’s degree and doctoral degree courses from 1 August 2025 onwards will also be increased by the same percentage.

The latter is a source of growing concern for students, and in particular access to the professions, given that PGT fees have been going up faster than each of the OBR RPI projections that DfE has long used to set these rates.

It remains a source of bafflement that DfE can’t get an increase past the Treasury, given the recovery rate – perhaps it hasn’t asked. It may be, given no sign of PG showing up in the LLE, that it will take ministers to extend the Access and Participation regime to PG, causing providers to lobby harder on PG loans, before we see a substantial change there.

It’s also worth noting that the Secretary of State took the opportunity to remind providers that for continuing students, the ability to impose the increase will also depend on their individual contracts with students, and “providers will wish to make their own legal assessment of contracts when considering fee increases” – an issue we’ve looked at and one covered on the AHUA blog too.

The Competition and Markets Authority is currently consulting on new guidance on unfair commercial practices (ie contract terms) as a result of last year’s Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act, and just last week Ofcom’s new outright prohibition on in-contract price increases for (most) telecoms contracts (on the basis that consumers can’t predict the impact of “uncertain and volatile” inflation) – that’s sort of policy environment where universities whose terms aren’t watertight would be very silly indeed to plough on and hope students don’t complain.

(Equality) impact assessments

Alongside the SI, DfE has also today published a three-part impact assessment on the fees and maintenance changes – the final stage assessment for the tuition fee and loan limits changes, one on lowering maximum tuition fee and loan limits for HE foundation years in classroom-based subjects, and another on the equality impacts of all of the above.

For the first of those, it won’t surprise you to learn that DfE thinks that in response to the growing financial challenges that the sector is facing, there are reported examples of some providers taking action to reduce the costs they incur and improve their financial position, “some of which could ultimately have a negative impact on students’ learning and experience”. That may be the full extent of DfE’s understanding of the impacts – given it goes on to say that:

…there have been examples of job losses at some providers, with others closing down certain courses, degree programmes or even entire faculties and departments with around 70 providers across the UK running restructuring and redundancy programmes.

The problem, perhaps, is that the source of that intel is listed not as its own Office for Students, who you might imagine would have a grip on that sort of thing – but the Queen Mary UCU branch’s “UK HE shrinking” webpage!

The (projection of) (RPI)m inflation increase is then posited as an answer to that problem, without really recognising that the increase won’t be enough to reverse those cuts, and falls even shorter when the NI increase imposed at the last budget is taken into account. You might, on that, have expected a provider-type, or at least sector-level analysis of the robbing of Peter to pay Paul – alas, adhering strictly to the rule that this analyses the fee increase policy not the fee increase plus other policies policy, all we get is a footnote reminding us that OfS puts that NI bill £430 million each year from 2025-26.

Amusingly, given assessments of impact tend to pretend that other options were on the table, the alternative option of increasing the cap by an amount greater than inflation was apparently rejected because “it would come at a cost to students, particularly those that are more debt averse, who would be less likely to pursue HE because they deem it too costly, even though they would benefit from it” – with the more likely culprit of Treasury concerns tacked onto the end.

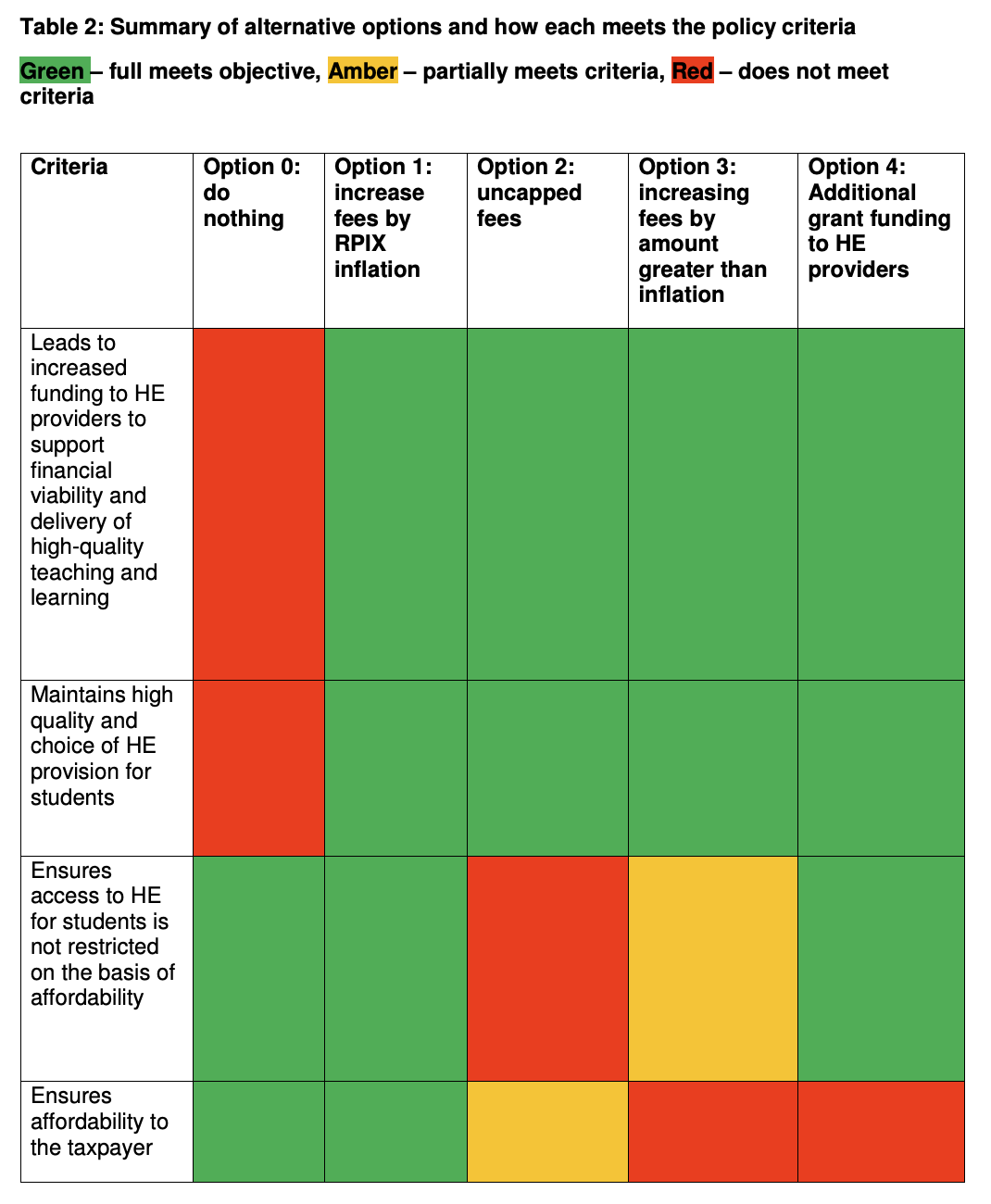

It’s the sort of document that produces tables like this, which you have to imagine a civil servant was very pleased with indeed once produced:

For the foundations year impact assessment, DfE belatedly seems to have clocked that the huge increase in foundation years since 2015/16 has been through franchised provision – not something it disaggregated when it produced stats (on worsening outcomes) to underpin the original decision to cut fees for classroom-based FYs back in 2015/16.

Apparently, the policy to cut fees was based in part on this IFF Research report on the costs of foundation year study that somehow interviewed a bunch of CFOs and trawled TRAC data but failed to look at the astonishing and arguably egregious profits being made by franchised providers in this space.

Either way, cutting the fee is obviously posited as good for students (with little modelling of what might happen to availability) and HE providers, we are told, will be encouraged to “deliver this provision more efficiently” or “consider whether more students can be offered direct entry to undergraduate courses”.

The third document – the equality impact assessment – is the usual work of art. In principle, DfE says that the planned student finance changes should not be significant enough to alter participation decisions since the impact of increasing support by forecast inflation means a nominal but not a real-terms increase in student debt.

It also says that the uplift to tuition fee and maintenance loans will only increase lifetime repayments for those borrowers who are already forecast to repay their loans in full – lower lifetime earners will see no increase in their lifetime repayments due to the loan increases, and no borrowers will see higher monthly repayments when they start repaying their loans.

My favourite part every year is the assertion that the increase in maintenance loan support should maintain the spending power of students at their current levels – refreshingly, this year DfE fesses up that it will not offset the significant erosion in the real value of SLC support which has occurred in the last few years due to the spike in inflation.

The problem is that that is evaluated not on how miserable some students are, or how thin their student experience is getting, or how much commercial debt they end up in, or whether they end up frozen out of extracurriculars, or whether they compromise their choices on provider or course, or whether they end up ill, or what their outcomes are like – but on whether they actually participate in HE. And on that:

So far, no clear evidence has yet emerged to indicate that this risk has materialised for students with protected characteristics or from disadvantaged groups. Data shows that HE acceptance numbers for the latest application cycle are higher than the previous year while progression rates into HE have held up for most protected groups.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again – young people are a pretty ambitious bunch. They’ll grit their teeth and survive through HE if they have to – and so measuring equality impacts of financial support policies exclusively through a “do they enrol or not” is a pretty shoddy way to treat people on often impossibly low incomes.

There is one line that says:

…survey evidence shows that students are increasingly turning to part-time employment to supplement the income they receive from their SLC loans, grants and allowances. However, we do not know the extent to which this is happening among students with protected characteristics or from disadvantaged groups.

If only, I don’t know, DfE had asked HEPI/Advance HE for their data tables on the subject, or us for our data on a variety of these issues including part-time work or students going hungry. I could even swear some DfE people were at our Festival of HE where I presented some of this stuff. All you have to do is drop us an email!

Cut through the document, and the upshots are that female, young (20 or under), those with a gender which is not the same as assigned at birth and toise that are bisexual, lesbian, gay or other sexual orientation are more likely to get a loan – and so more likely to end up in more debt – and disabled students are more likely to be debt averse because they have additional learning requirements which increases the cost of study that they face.

That’s all traded off against there not being the provision or current costs support in the first place, depressing their participation – and the lack of predictability in how providers will respond on the FY cuts produce similarly inclusive equality impacts.

Alarmingly, the other thing never covered in these EIAs on student finance is the family income threshold over which we expect a parental contribution. The reason for that is doubtless “well that’s not a policy that’s proposed to change, and so not evaluated for its equality impacts” – but the fact it has been set in aspic since 2007 rather than rising with earnings produces quite dramatic equality impacts if you ask me. Which is probably, to be honest, why they haven’t.