Despite often being accused of individualism and treating education as a transaction, students generally seem to be a pretty fair-minded and community-oriented bunch to me.

Some students on some subjects are more expensive to teach and support than others. Some need the library more than others. Some use the sports facilities. Some avoid them.

Some will never go near a counselling team – but you don’t often hear those that don’t complain about those that do.

I suspect there’s a few reasons for it. One will be the abject lack of clarity about where the money goes. One of the reasons will be that most use some things/services/spaces, and they get that few use all.

And you can see why students might assume that the government is putting in a substantial chunk of money in – even though the long-run real contribution is through the floor.

Crackle and pop

But it seems to me that the web of cross-subsidies, internal choices and diversity of people, subjects and “stuff” can only hang together for so long. At some point, it snaps.

So across subjects and pathways, for example, students don’t seem to mind (or notice) that the personal tutor in one area has ten students to support, and in another, five.

But when – within one university – some people actually have one, and others have group tutorials as large as their lectures, snap.

When providers are doing portfolio reviews, it is indeed often a tragedy that programme X, subject area Y or module Z gets contemplated for closure over recruitment.

But when the way that’s hanging together is by offering those bankrolling the place through international PGT fees an SSR of 1 to 60, snap.

I’m guessing that the only reason that students down the bottom half of the league table aren’t up in arms about those in the top end having more money to spend on fewer students that need help despite both paying £9,250 is that the further down the tables we go, the less likely it is that students will have the knowledge or social/cultural capital to be up in arms.

I was thinking about all of that this week at the European Network of Academic Sports Services’s annual shindig in Belfast.

Did I say that?

I’m not simplistically saying that this is what happens, but if (for example) you run a function that spends a lot of money on an a small number of elite sportspeople, the rest on kickabouts for home students and nothing on the international PGTs bankrolling the whole place, you may have some strategic thinking to do. Snap.

Following my 90-slide post-Festival thriller, was a superb presentation from the Manchester United Foundation’s CEO John Shiels, who’s been partnering with Ulster University over a project in Derry.

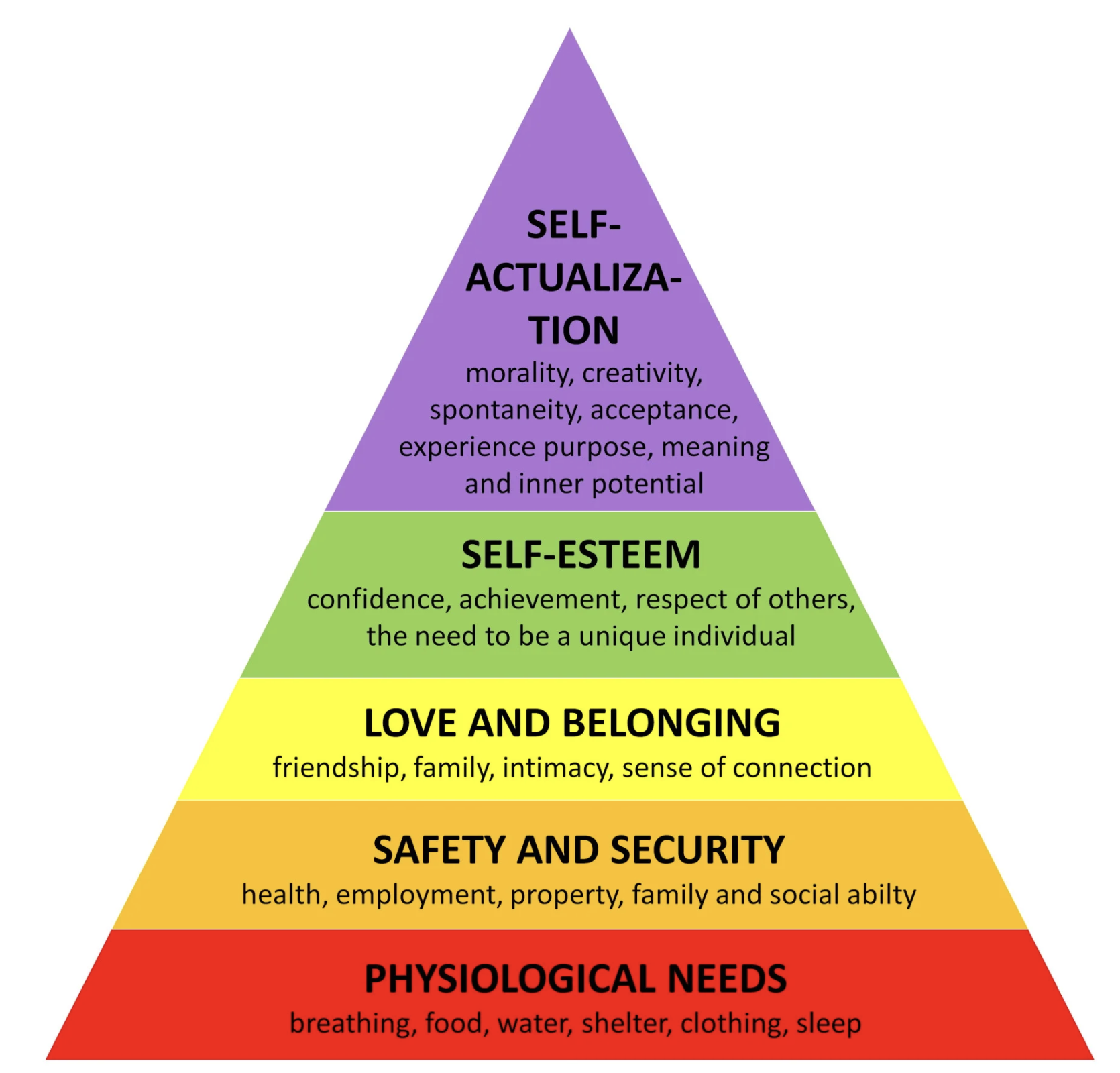

Shiels talked of the way in which he’s had to shift some of the focus of its work from self-actualisation in Maslow’s hierarchy to the basics of shelter and food.

I suspect plenty of people think of universities as being in the self-actualisation business – places that never had to think about the 4 levels below.

But as higher education massifies, and states (right across the West) become less reluctant to pay for the expansion given zero-real growth and ageing populations, it’s hard enough to offer all the self-actualisation on the “unit of resource” – let alone deliberate belonging, or social confidence, or safety, or food.

All of that is someone else’s job, surely?

But of course if you believe in Maslow’s hierarchy as a stacking set of dependencies, hungry students just off a night shift in an Amazon warehouse in a freezing cold house aren’t nattering into the night about the lectures they’ve just been in.

They’re tired, hungry and cold. And being in Belfast at 7am the day after our Festival, I know how that can prevent me from delivering a decent presentation, let alone if I was this tired, hungry and cold all the time.

Doing all the extra bits of Maslow on no extra money or no extra time can feel like it’s too much for students and staff – either because it’s not what people signed up for, or because it removes time for the self-actualisation joys of teaching, research and all of that “growing as a person”.

Boxes and buckets

At the Festival, one of our fantastic student experience panellists talked of how overwhelming “filling the buckets” can be particularly for those without family experience of HE – the academic work, the networks, the work experience, the volunteering and so on.

Not only do you not know how to navigate it all – or which bits are actually valuable – you have less time to get those judgements wrong.

Shiels talked vividly of kids his charity with having quite small worlds – the park, the school and home. Multi-million pound sports centres of the ilk the event was held in “look like Disneyland”.

But you’re then left with choices. Get people into Disneyland and let them know it’s really for them? Or give them a blanket because they’re cold and then they’ll figure it out for themselves?

Lots of people can make the case for the latter. Poor communities are famously adept and resourceful at figuring things out for themselves as long as they’re not scratching around for money for the meter.

And our polling work on food and safety and belonging also suggests that focussing there can be more impactful than making seminar slides easier to read.

But it does reel us back to that cross-subsidy point.

Me me me

The point about the way we’ve individualised the contribution to higher education is not just that the sector sells unattainable dreams – it’s that it’s sold something to someone.

And as I say, most of those someones don’t mind moderate cross-subsidies. But once you’ve had your heart set on some self-actualisation – and either having to share it so thinly as to make it like a theme park on a bank holiday, or you’re closing the “thing” because it isn’t shared by enough people, you start to feel mugged off. Snap.

The news, for example, that UWTSD might have to deal with the “Lampeter problem” is a case in point. Birthplace of HE in Wales, historically important, community implications and so on.

But given we have a demand-led system where the vast bulk of funding now comes through delayed private contributions, why should students in Swansea or Camarthen poke up with “less” to prop up a campus with less than 100 undergraduates studying at it?

Why wouldn’t that be the job of the state?

Over time, as the fog clears on massification and private contributions, I fear that the room, commitment and case left for collective cross-subsidy melts – at just the point that states want to load more and more of their function onto universities.

It’s all very well for Bridget Phillipson to be demanding efficiencies and better value, but the long-run cost of the teaching and student support end of English HE is currently £3bn a cohort – down from £5.7bn in 2019.

Just how much more efficient – and more Maslowy – can the sector get? And if that involves shuttering the things people who just need Level 5 thought they were paying for, what then?

But I do think a “deal” might be possible.

As I said above, students generally seem to be a pretty fair-minded and community-oriented bunch to me. If ways could be found – through cost reduction and credit recognition (and therefore time allocation) – to make serving others (both students and communities) a core and universal component of the UK higher education experience, we might just be able to maintain the idea that sometimes it’s worth putting food on at the forum – because it makes that forum better for everyone.

It’s the difference between charity and community development.

The more that space is created for students to survive and create, the less the sector will have to do it for them. Because maybe in a mass system we’ll never be able to afford or achieve the equivalent of everyone being able to do the West End theatre school trip. But school plays sell out.