Universities may be getting a bailout. But will students?

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

On Sky News and GB News, Bridget Phillipson was pressed on gender guidance for schools, private school fees and pupil’s access to mobile phones.

Who ever said that journalists only focus on the issues that the Times, the Telegraph and the Mail seem concerned with?

The good news is that university finance also made it in on the BBC’s version of the exercise. Laura Kuenssberg wanted to talk about an issue that’s “a big concern to lots of families, and lots of staff and lecturers and universities around the country” – that many universities are in real financial difficulties.

Would Phillipson use taxpayers money to bail out a university that might otherwise go under?

It’s miserable that we’re having to pick the clues out of the waffle given that we’re about to go to the polls, but we are where we are.

First the vibes. What Phillipson could say “very clearly” was that Labour will make sure that:

…once again, universities are recognised as the engines for growth across our country, a public good, not a political battleground. We will not denigrate them in the way the Conservatives have done. We will deliver a better system that is better for taxpayers, better for students and graduates and secures a long term future for the sector.

That all sounds like some medium term review is in the offing. But what about the more immediate issues?

Heads above water

Kuenssberg asked if she was saying to students, parents, and maybe even university vice chancellors who might be watching this morning (Kuenssberg even said “good morning to them if they are” at this point) that if you win the election, you would not let universities go under – you would do whatever it takes to keep them afloat?

We are determined to maintain the world leading status of our universities. They are renowned around the world. They are one of our best export industries and within our towns and cities, they provide opportunities for adults, not just young people to get back into training to get a second chance where maybe things haven’t worked out first time around – there are so many great examples of where that is happening.

They will be essential to our plans to drive economic growth to make sure that right across our country, people have access to well paid highly skilled jobs and there will be a different relationship with our university sector if Labour wins because we know that they are so important in so many communities like my own.. that is why we we have to have a different approach.

The thing that had preceded the warm words was the confusing bit. Phillipson argued that the challenge Labour has in opposition is that they know the government has been doing work in this area to understand the full extent of what’s going on – but that she doesn’t have the same level of access to that:

But I think we do have to try it with real care here because universities right across our country and our towns and cities are really important engines of growth and opportunity and jobs. And I would want to avoid any disruption happening to young people’s education whether or if an institution were to run into trouble and that would be the outcome.

Phillipson added that the Office for Students has been looking at this area, and is:

…publishing some recommendations about how we get to a stronger fiscal position for a university because as you’ve just said, this is a very real issue. And it’s a very real issue right around the country.

It’s not clear whether BP meant OfS’ Financial sustainability of higher education providers in England: 2024 report or something else – but Kuenssberg did push her on the bailout principle:

It’s a question of principle. Would you use, if you win the election, taxpayers cash to bail out or university?

Given the available data it might surprise readers to learn that Phillipson didn’t “believe that will be necessary”, although added that “there are measures that can be taken to stabilise the sector that will be a day one priority.”

Sher wouldn’t be drawn on what those measures might be other than to “strengthen financial regulation and oversight of the sector” because:

…the modelling on this is incredibly difficult, and we simply do not have the same level of access to… Treasury modelling and ongoing discussions… about the health of the sector.

We might imagine that if you add all of that up, we could be looking at a 2024 version of the Covid-era Department for Education (DfE) proposed Higher Education Restructuring Regime (HERR), which was to provide loan support for providers in England facing financial difficulties.

I could write a book on what leads to the state of universities’ budgets making it onto broadcast journalists’ agendas but not students’. But plenty of students are on (or over) the brink too.

Students below the surface

In January 2004, partly to sweeten the pill over proposals to raise fees to £3,000, then Secretary of State for Education and Skills (Charles Clarke) announced a new package of student finance to ensure that “disadvantaged students will get financial support to study what they want, where they want”.

From September 2006 there were to be new higher education grants – and maintenance loans were to be raised to the median level of students’ basic living costs as reported by the student income and expenditure survey – to ensure that students have “enough money to meet their basic living costs while studying”.

The aspiration was to move to a position where the maintenance loan was “no longer means-tested” and available in full to all full-time undergraduates, so students would be treated “as financially independent from the age of 18”. And the new Office for Fair Access was to be required to issue additional bursaries to students.

By July 2007, the then new Secretary of State for Innovation, Universities and Skills, John Denham, went further with new reforms to support for (undergraduate) students in higher education (from England) – to recognise that hard-working families on modest incomes had “concerns about the affordability of university study”.

The rhetorical flourishes are all pretty similar to those we hear today – but we should, for the sake of argument, look at what has happened since. Even though by the time the changes were implemented the SIES data was a few years old, at least the “we’ll fund basic living costs” principle was there.

In 2007 DIUS ministers had not been able to persuade the Treasury to abandon means testing – but full grants were to be made available to new students from families with incomes of up to £25,000, compared with £18,360 – along with minimum £310 bursaries from higher education institutions.

The announcement was accompanied by a document with some handy case studies – Student A, whose parents who had a combined household income of £50,000 and who had a brother who already studying at university; Student B, from from a single parent family with a household income of £20,000; and Student C, living with both parents who had a residual household income of £25,000.

Here’s what they were entitled to at the time (away from home, outside of London):

| Student A | Student B | Student C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Household income | 50000 | 20000 | 25000 |

| Grant | 560 | 2825 | 2825 |

| Loan | 4070 | 3370 | 3370 |

| Guaranteed bursary | 310 | 310 | |

| Total | 4630 | 6505 | 6505 |

That £25,000 household income threshold hasn’t moved since; there’s now no grants (only loans); nobody’s guaranteed a bursary; and both prices and incomes have risen since.

So to see how far things have fallen, let’s see what those three students would be entitled to now. Student A’s parents now earn around £83,500; Student B’s single parent family now earns around £33,400; and Student C’s parents earn around £41,750.

| Student A | Student B | Student C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Household income | 83500 | 33400 | 41750 |

| Maintenance loan | 4767 | 9497 | 8035 |

Now let’s adjust those totals to 2008 prices (RPI) to look what what they’re worth:

| Student A | Student B | Student C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintenance loan | 2569 | 5117 | 4330 |

So the comparison in 2008 prices shakes down as follows:

| Student A | Student B | Student C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 4630 | 6505 | 6505 |

| 2024 | 2569 | 5117 | 4330 |

| Inc/Dec | -2061 | -1388 | -2175 |

| -45% | -22% | -34% | |

And if we take HEPI’s minimum income standard as a way of judging the gap between state (loan) support and what students need – the implied parental/part-time work contribution – we can see the problem in another way as follows (all figures adjusted for 2024 prices via RPI):

| Student A | Student B | Student C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | £10,040 short | £6,561 short | £6,561 short |

| 2024 | £13,865 short | £10,135 short | £10,598 short |

The other thing we could do is look at the official stats that the DWP holds on income – which it uses to produce estimates of poverty.

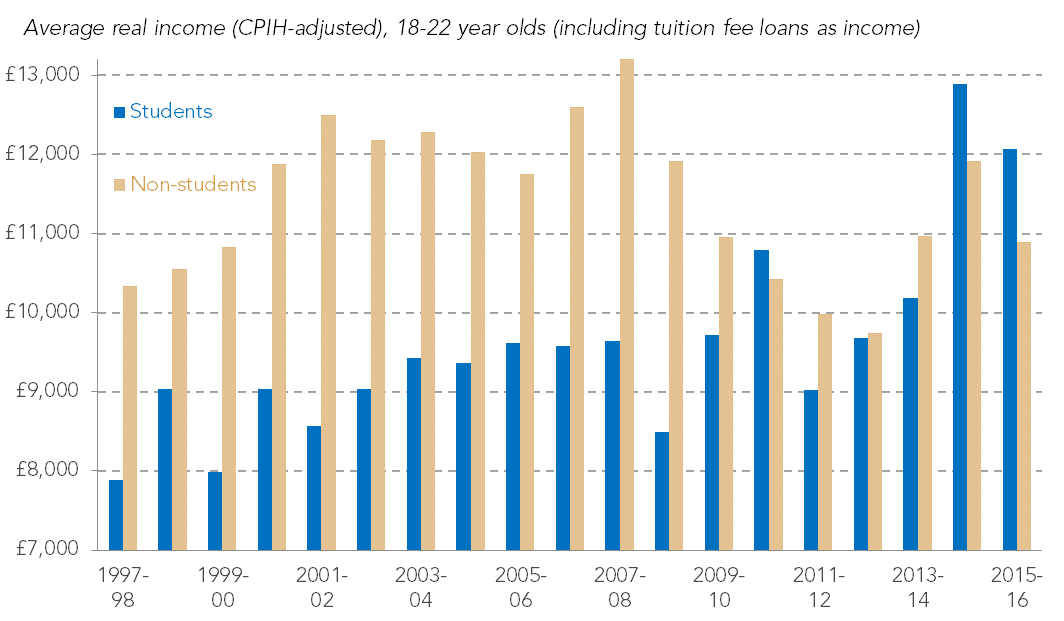

For students the data is plagued with quality issues (students not being the DWP’s problem, of course so for example nobody in halls is even counted) but again, one thing is clear – the country’s official stats on poverty preposterously count tuition fee loans as income.

We can see the way in which the large jump in tuition fees between 2011-12 and 2014-15 distorts the picture (the immediate impact of tuition fee increases gets blunted / delayed because students in halls of residence (more likely to be first years) are not surveyed, the time it takes for all students to be affected, and academic vs financial years):

I guess the point is that pending some sort of major review that gives the new government some notional time to build the case for a) changing the fiscal rules, b) establishing the problem (oh good grief look what we’ve found) c) finding some extra money and/or d) trying to wrestle some control of the “more graduates, just not in these subjects and these parts of the country” problem, doing bridging loans to universities while they restructure is an option.

Hence maybe on “Day One” Phillipson et al will be having meetings with OfS, pouring over its “Financial Sustainability of Higher Education Providers” data. But don’t bet that the office bearing students’ name is producing “Financial Sustainability of the Students Attempting to Take Part in it” data. And without it, what passes for a bailout plan will be pretty much a waste of time.