What did we learn from Labour’s tuition fee announcement last week?

The headline message seems to be about small adjustments, rather than radical reform.

There’s some potential good news for poorer students and graduates, but little for universities feeling the financial pinch.

Effective tax cut

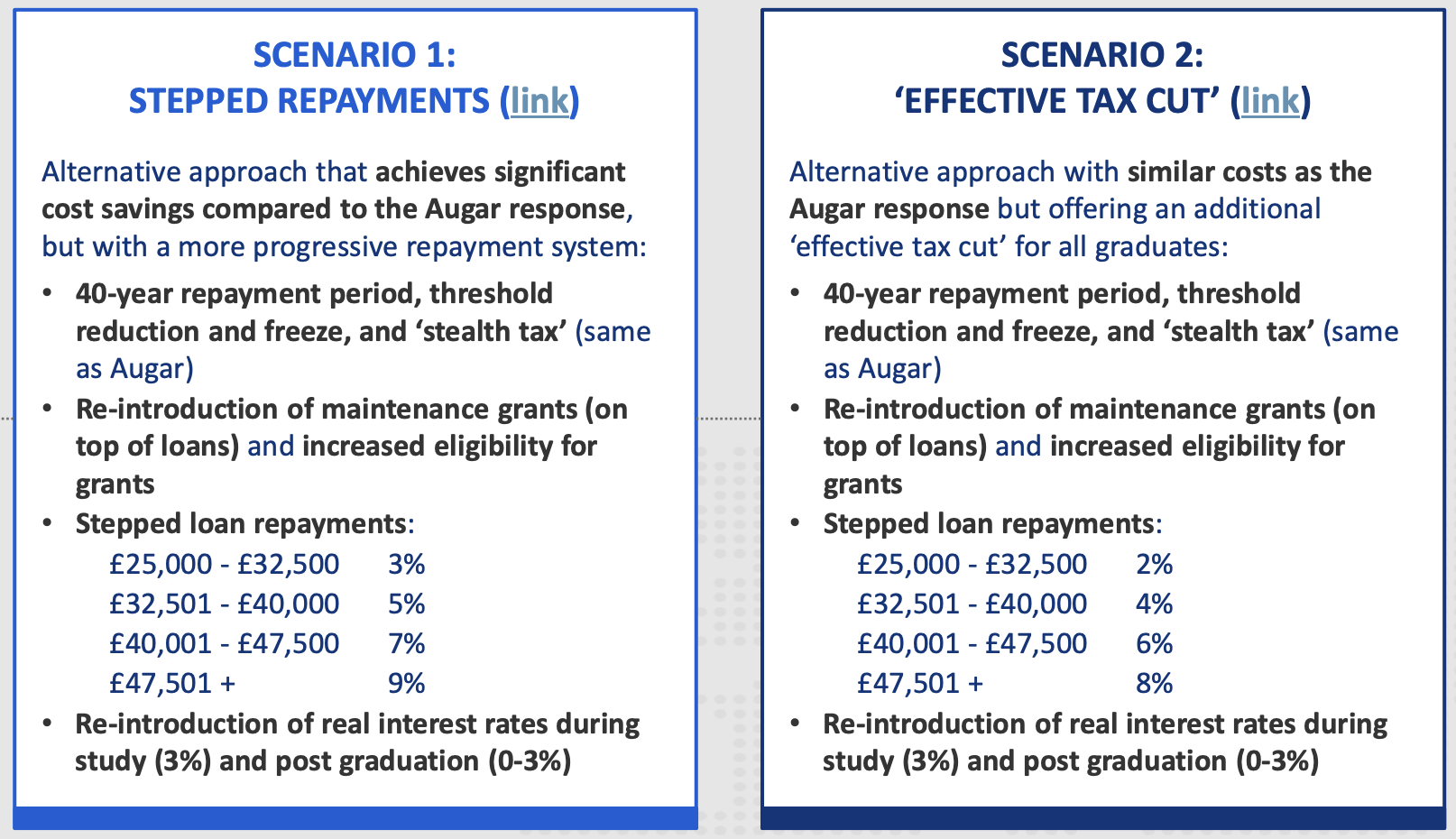

The core message, “graduates, you will pay less” has to mean either reducing the repayment rate or increasing the threshold at which repayments start. The popular guess is that this means something along the lines of the “effective tax cut’ scenario proposed by London Economics last month.

One might think this would be popular – and no doubt Labour are hoping it will be. However, Phillipson would do well to consider what happened in 2017, when Theresa May sought to lower graduates’ repayments, following the 2017 General Election.

Strong and stable

Driven by a belief that Corbyn’s overperformance had been caused, in part, by his pledge to abolish tuition fees, May raised the repayment threshold from £21,000 to £25,000, causing every graduate earning over £25,000 to save £360 a year. This change was phenomenally expensive – costing £2.3 billion a year – but won her almost no gratitude whatsoever.

Labour will reform this system. With our mission to break down barriers to opportunity, we will make it fairer and ensure we support the aspiration to go to university. Plenty of proposals have been put forward for how the government could make the system fairer and more progressive, including modelling showing that the government could reduce the monthly repayments for every single new graduate without adding a penny to government borrowing or general taxation — Labour will not be increasing government spending on this. Reworking the present system gives scope for a month-on-month tax cut for graduates, putting money back in people’s pockets when they most need it. For young graduates this will give them breathing space at the start of their working lives and as they bring up families. This is a choice that the Tories could be making now to deliver a better, fairer system for our graduates and for our universities.

What’s more, if we take seriously the pledge that this will be done “without adding a penny to government borrowing or general taxation”, that almost has to mean putting interest rates back up. That’s a problem: high interest rates are loathed by students, graduates and parents alike.

Salience trumps reality

To the frustration of wonks everywhere, there are only two salient issues in fee policy that cut through to the public – the headline rate of fees and debt; and the interest rate. You can produce graphs showing that high interest rates are technically progressive until you’re blue in the face, but it’s one of the few areas where people’s gut instinct of what is fair, and what is actually progressive, don’t align.

A system where interest rates are no higher than inflation, so that no-one will pay back more, in real terms, than they paid in is intuitively felt to be fair. Tony Blair, arguably the most canny political operator of our time, understood this, and it was a fundamental concept that underpinned the system of student loans in the New Labour era. Introducing swingeing rates of interest in 2013 toxified the system – and it is no coincidence that fees have only been raised once since then.

We already have a very effective means to deliver progressive taxation – it’s called income tax. If you want to deliver more progressive taxation, changing income tax rates is far better targeted than introducing arbitrarily high rates of interest into your higher education funding system – not least because you can target the whole population, rather than the minority who are graduates.

Buy now, pay now (and later)

There’s a second big problem, and it’s that you can’t use a future asset – the additional money you will hypothetically receive from graduates in 30-40 years’ time – to directly pay for a current expense, such as reduced repayments or new maintenance grants. Even if the nominal cost to the Treasury is the same, additional cash now requires additional borrowing. I’m going to go out on a limb, therefore, and say that the claim that reducing monthly payments can be done without additional borrowing will end up being incorrect.

Now for the good news: it seems that the poorest students may get a maintenance grant. It’s not promised, but it’s how I read the bits about it being bad that poor students are having to take on more part-time work. Restoring maintenance grants is a very reasonable thing to want to do – but it has consequences.

In making the system fairer we must also recognise the pressure that the cost of living crisis is putting on students during their studies. Every time I visit our world-class universities, I meet students taking on extra hours or new part-time jobs to cope with rising bills. The Tories’ economic mismanagement is hurting students’ studies and their chances: more hours spent earning means less time spent learning. That’s affecting the grades students can achieve. And all too often it’s students from lower-income families, sometimes the first in their family to go to university, who are struggling the most.

The freeze continues

For universities rightly worried about their finances it means that maintenance grants and lower repayments look likely to be prioritised over any increase in the funding per student. And that’s before we even consider the pressure to spend more on teacher pay, schools and childcare, all of which are likely to be priorities for a Labour government.

In fact, we’ve not learned anything about how Labour plans to relieve the funding pressures on universities – or even if they intend to do so at all. One could fairly argue that this was an op-ed focused on students and graduates, not a comprehensive policy paper – but again, it shows where Labour’s priorities lie: and that is with graduates and low-income students, not with universities.

A university education is an incredible opportunity for each of us and for all of us. Higher education doesn’t only benefit the people who go to university, it enriches our society, our culture and delivers innovations that can lead to better lives for us all.

The lines about university being “for all of us” are also a concern for anyone worried about affordability or course quality. It would be a big departure from the Robbins principle, which argues that it should be “available to all who were qualified for them by ability and attainment.” In practice, it may not mean a significant departure from current policy, but as I argued earlier this year in a debate at Policy Exchange, ultimately, the only way of securing sustainable funding for either universities or students is to regain a measure of control over how many people go. If she does end up in No. 11, Rachel Reeves is unlikely to be any keener than Rishi Sunak or Jeremy Hunt on writing blank cheques.

Ultimately, tinkering with repayment and interest rates will create both winners and losers, and whether or not you think the end results are fair will depend on both your perspective and your baseline.

Either way, it is unlikely to win Labour as much gratitude as they no doubt hope. There’s little in what we know of Labour’s proposals that could be described as actively bad. But neither is there anything – so far – that will solve the long-standing pressures of the current system.