There is much institutional showboating around equality, diversity, and inclusion – both in the private sector and in higher education.

But what happens to the people, often from minority groups themselves, who conduct this work on behalf of institutions and what effect does it have on their careers and workloads?

Drawing on our recent research we have found that, and argue that, something far murkier is going on around the experiences of those trying to make change on the ground in universities and individual departments.

SWAN above the surface

The Athena SWAN charter, the gender equality charter widely adopted both in the UK and Republic of Ireland, and increasingly in a number of countries around the world was reviewed in 2020, with many in positions of power hailing its efficacy and contribution to gender equality in higher education.

Yet for many people conducting the day-to-day data collection, document preparation and award applications, there are real costs. Those who engage in and are involved in equality work and actively representing women and minorities are often not institutionally rewarded for their work, but rather have their identity taxed.

Whilst there is indeed acknowledgement of the workload and burden associated with Athena SWAN and other equality charters, consideration of the effects on those carrying out the administrative work of “winning” the awards, the price that individuals are paying is deeply personalised and identity focussed price for institutional reputational gain.

Respondents of the 2021 Wonkhe community survey which explored what the HE sector should focus on to make real change, highlighted the endemic sectoral gaps between rhetoric and action and concrete change. This is also painfully clear in the lack of change arising from the Race Equality Charter.

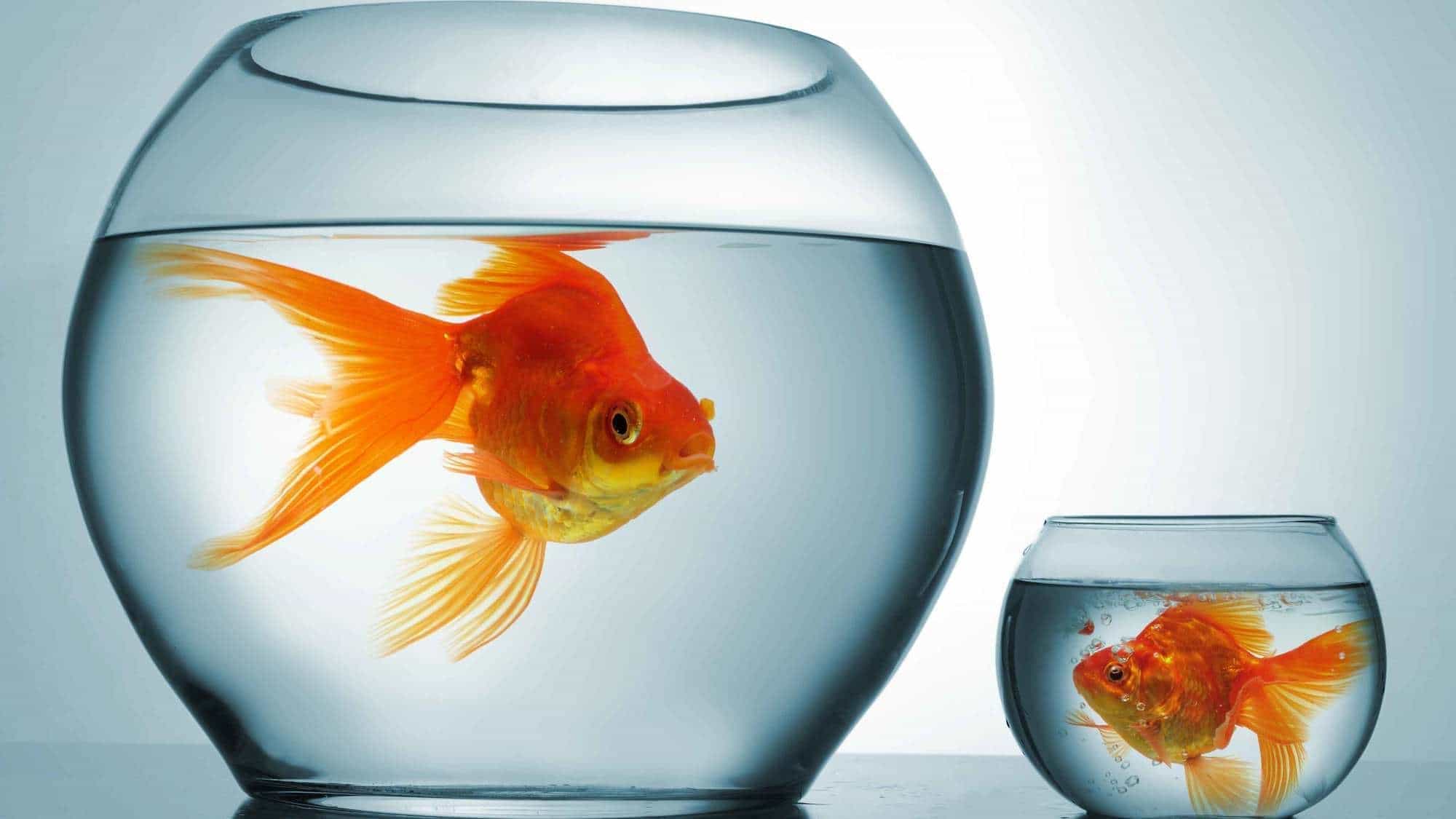

Drawing on insights from 35 Athena SWAN champions in the UK and Republic of Ireland, we found that equality work in multiple universities, and potentially also other organisations, overburdens those already carrying out equality work for the benefit of the institution, with deleterious effects for themselves.

For women, and other minorities who actively represent others, their labour is capitalised on for equality accreditations such as Athena SWAN. Yet it is also poorly resourced, under recognised, and leads to a “taxation” of their identity and results in representative labour – whereby the organization extracts additional labour in the context of managerialism to achieve its performative goals.

Under the surface

While there are of course success stories associated with gender equality charters, for many who do this work, the picture is far bleaker. Institutions extract labour for “the cause” primarily from those whom equality charters were designed to support, rather drawing reputational gain and positive PR surrounding equality and diversity.

Athena SWAN champions are often called on to be the expert on equality, having to educate the majority group about diversity although this is not part of the job description and often not given any authority or recognition for the additional responsibility, with little real structural change to the organization, all whilst also being burdened by a moral obligation to demonstrate good citizenship towards the organization with a commitment to diversity, but no recognition.

Ultimately, academics and administrators who are engaged in equality charter work such as Athena SWAN, face career sacrifices and administrative burdens, in a context of institutional goals of financial reward, aggressive reputation building, and metrics in a brutally competitive higher education market.

Representative labour is at odds with the aims and objectives of equality and diversity schemes, but are the true aims and objectives true to the cause or designed rather to further the neoliberal goals of a deeply marketized sector?

In the longer term, this holds the potential to actively contribute to further regressions in gender equality, in a sector that is also seeing the lagged effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and home working on women scholars and anyone with caring responsibilities.

Institutions must ask themselves how better to protect employees who often give so selflessly to the institution and their colleagues, and how they can resource and support work that is apparently so intrinsic to their institutional values and missions – to in turn really contribute not only to equality but a workplace culture that recognises and rewards the labour of those they claim to value.

I have been heavily involved in EDI efforts in a number of roles but honestly in 2022 I think the advice for most staff is to stay away from this sort of work – as noted there is a ‘tax’ on the people who do the work, many Universities aren’t really committed and worse of all – when the cranks come for you – your University will hang you out to dry.

Thank you for your comment, Alan. Unfortunately, this was indeed the view and experience of several of our participants also.

Thank you for your involvement in EDI initiatives, and solidarity.

Emily