Inflation for Chevening scholars is much higher than it is for home students

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

The standard Department for Education line is that:

…the maximum maintenance loan will rise in line with inflation to help students cope with costs.

In its own words, sustained increases in prices and the cost of living reduce the real value of money, in terms of the quantity of goods and services that a given amount of money will buy:

…increasing the maximum level of student support available across these different streams of funding in line with forecast inflation aims to ensure that students do not suffer a real reduction in their income.

The problem in recent years is that the measure chosen – an OBR projection of inflation (RPIX, which is the discredited RPI plus housing costs) for the third quarter of the academic year in which the increase will apply – has been consistently wrong, and consistently lower that the reality.

That means, for example, that unless something major changes, we are heading towards the reality of inflation being about 4.5 per cent for this new academic year – when the uplift via the projection was only 3.1 per cent.

That’s worse when you factor in that food inflation is running at about 5.1 per cent given that students spend more of their money on food. Then factor in that students are more likely to buy at the bottom of the brand hierarchies, and/or raw materials –

Those rising food prices are also driving the loss of “third” social spaces like cafes, and the student jobs in them – it’s retail and hospitality where the bulk of closures and job reductions have been over the past year or so.

One of the most frustrating aspects of migration policy is the way that the Home Office’s rules on the “financial requirement” (the money students need to show they have on entry) are described. It implies that its figure is “enough money to support yourself” – but last year it set it at DfE’s broken maximum maintenance loan figure – and hasn’t even been bothered to put in place annual uprating.

But on the basis that, for example, UKRI is independent of government over PGR stipends, and the DWP isn’t really focussed on students at all, the question is whether any other bit of government itself uses a different measure of inflation for students.

Welcome to the UK

The Chevening Scholarship Programme is a UK government (Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office) initiative aimed at cultivating leaders, decision-makers, and future influencers from around the world. It’s basically a ticket for high-achieving professionals to pursue postgraduate studies, usually a one-year master’s degree, at UK universities.

Scholarships – often funded in partnership – cover tuition fees, travel costs and a stipend living allowance. Getting hold of the actual figures for that stipend is difficult – they’re not published routinely anywhere, but thanks to the magic of FOI, I’ve been able to work out how they compare to home domiciled living costs support and how inflation applies.

If we exclude, for a moment, bits in the rates for partners, arrival, children and the allowance for “warm clothes” (!), the headline (non-London) rate this year is £1,452 a month – and students get at least 12 months, so £17,424 as compared to the (max) £10,544 an undergraduate from England can pull down, or the £10,224 that international students are told to bring – and home domiciled PG students get even less once they’ve paid tuition fees.

We can quibble about whether the baseline amounts are comparable – these are a very distinct set of students with different working rules, academic expectations and so on, along with different backgrounds. You can make the case that a scholarship of this sort shouldn’t expect a parental contribution, too.

But what’s more interesting is how inflation has been applied. It turns out that it has an agreed formula, reviewed regularly, for increasing the annual stipend rate for the three government-funded scholarship schemes for international students – Commonwealth Scholarships, Chevening and Marshall.

Not only does it use CPI rather than RPIX – and a “current” rather than “projected” measure at that – it even varies from that rate a bit based on the basket of goods it thinks that these students buy.

Basket case

This year, the application of the formula to Consumer Price Inflation (CPI) figures resulted in a 5.4 per cent uplift in the stipend rate for the three programmes, building on a 3.5 per cent increase in CPI in April.

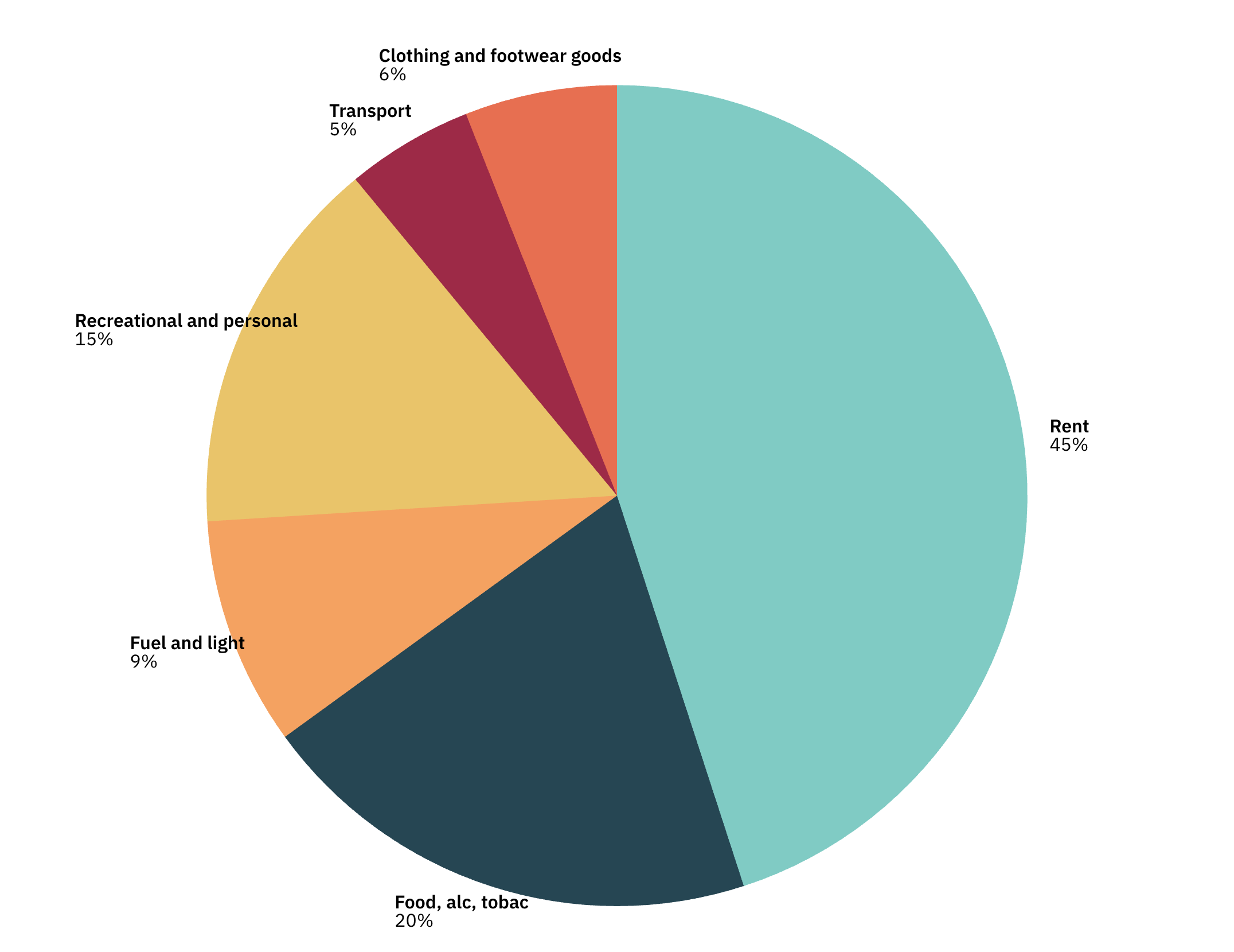

The formula uses a set basket of indices from the Consumer Price Index which were specifically chosen to reflect the main areas of spending for students. So for example, their main cost is on rental for housing, which carries a weighting of 45 per cent in the calculation that determines the stipend.

This formula is then applied annually in May on the release of the April Consumer Price Index, for increases applicable from October, and the percentage inflation for stipends is a weighted average of the percentage increase April to April of the value of each of those indices, calculated using the weightings below:

You might, for undergraduates, weight slightly differently, based on an analysis of what they tend to spend. And that 45 per cent weighting for housing looks… optimistic.

But in principle, this is exactly the sort of approach that we ought to expect from governments when using “inflation” to determine increases.

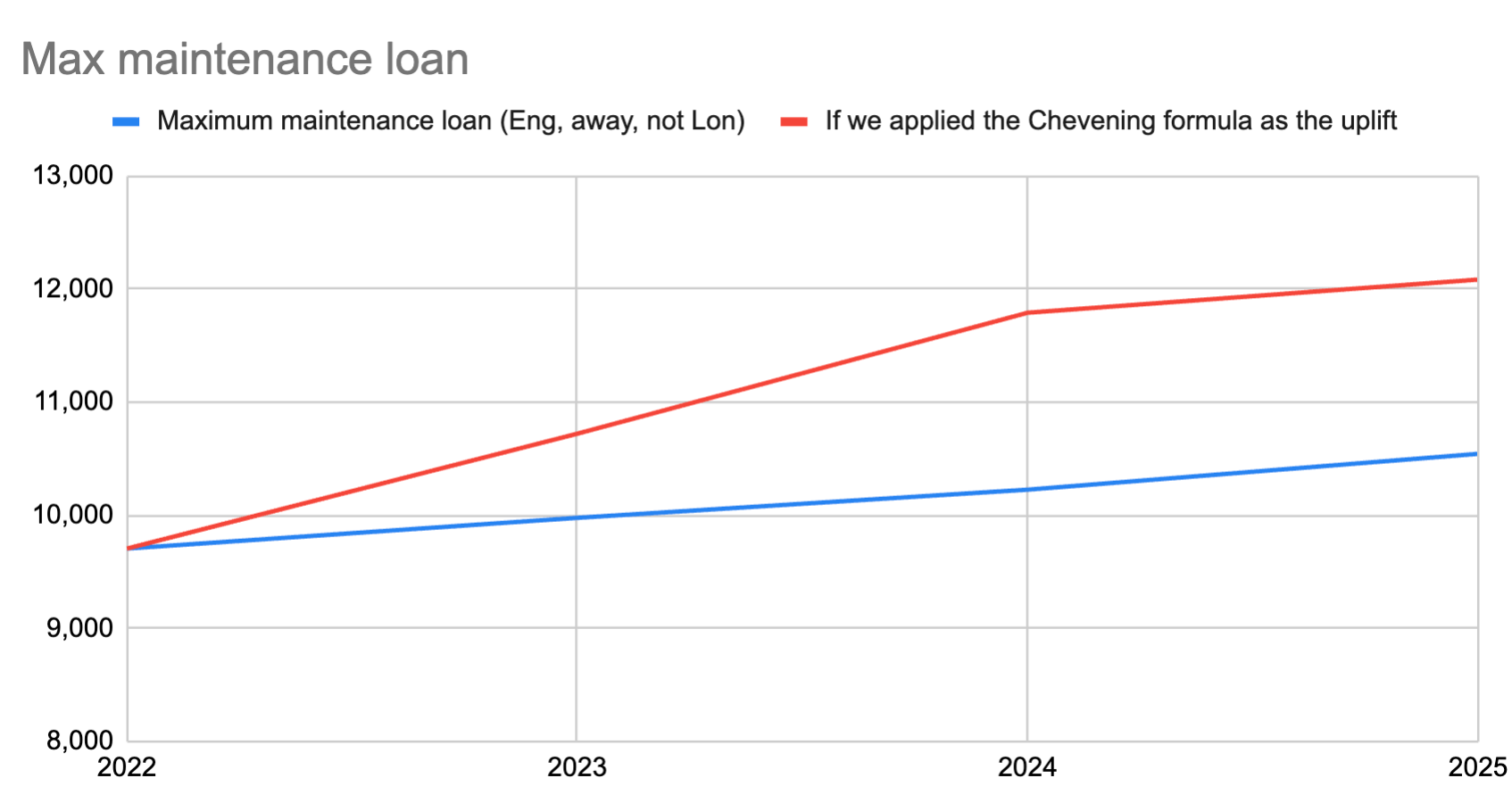

In 2022 Chevening scholars were on a stipend of £13,596 a year, while the max England non-London away from home maintenance loan was £9,706.

But if we ignore that disparity, and the fact that the means test in the maintenance loan is broken (fixed at a threshold of £25,000 since 2007), if we just took 2022 as a baseline and applied the Chevening basket formula (the weightings plus the use of previous April CPI) to the max England non-London away from home maintenance loan, here’s what the uplifts would have looked like:

Choices ahead

Skills minister Jacqui Smith says the government recognises “too many students” are facing real financial hardship:

That’s why I am determined to fix the foundations of higher education to deliver change for students – restoring universities as engines of growth, aspiration and opportunity.

When the Skills White Paper appears, it’s unthinkable that it doesn’t address maintenance. As a minimum, ministers will need to set a new baseline based around real costs. But then it will also need to pick a proper basis for the annual uprating of both the means test threshold (which obviously needs to be avg earnings) and the core maximum.

Phillip Augar’s Post-18 review of education and funding proposed uprating via the national minimum wage – that didn’t happen. Wales was set on that until it wasn’t. Scotland said it would use the Living Wage – it managed that for one year. This Chevening method would do. Anything other than the OBR’s increasingly useless projections would help.

Interesting that WonkHE is capable of providing analysis comparing uplifts to inflation. How about applying that same attitude to analysis about staff pay and potential industrial action?

Why the “(!)” after “warm clothes”? The climate and temperature is not the same in a tropical developing country as it is in the northern hemisphere during Winter. Suppose the student maintenance grant was increased substantially. How would this be paid for? By workers without degrees paying more taxes? By reducing the schools budget? By placing a levy on overseas students?