Why are we panicking about mature student participation?

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

They’re often accompanied by discussions surrounding the barriers facing adult learners.

But the idea that mature student numbers have declined dramatically – a situation requiring urgent policy intervention – depends on which data you look at.

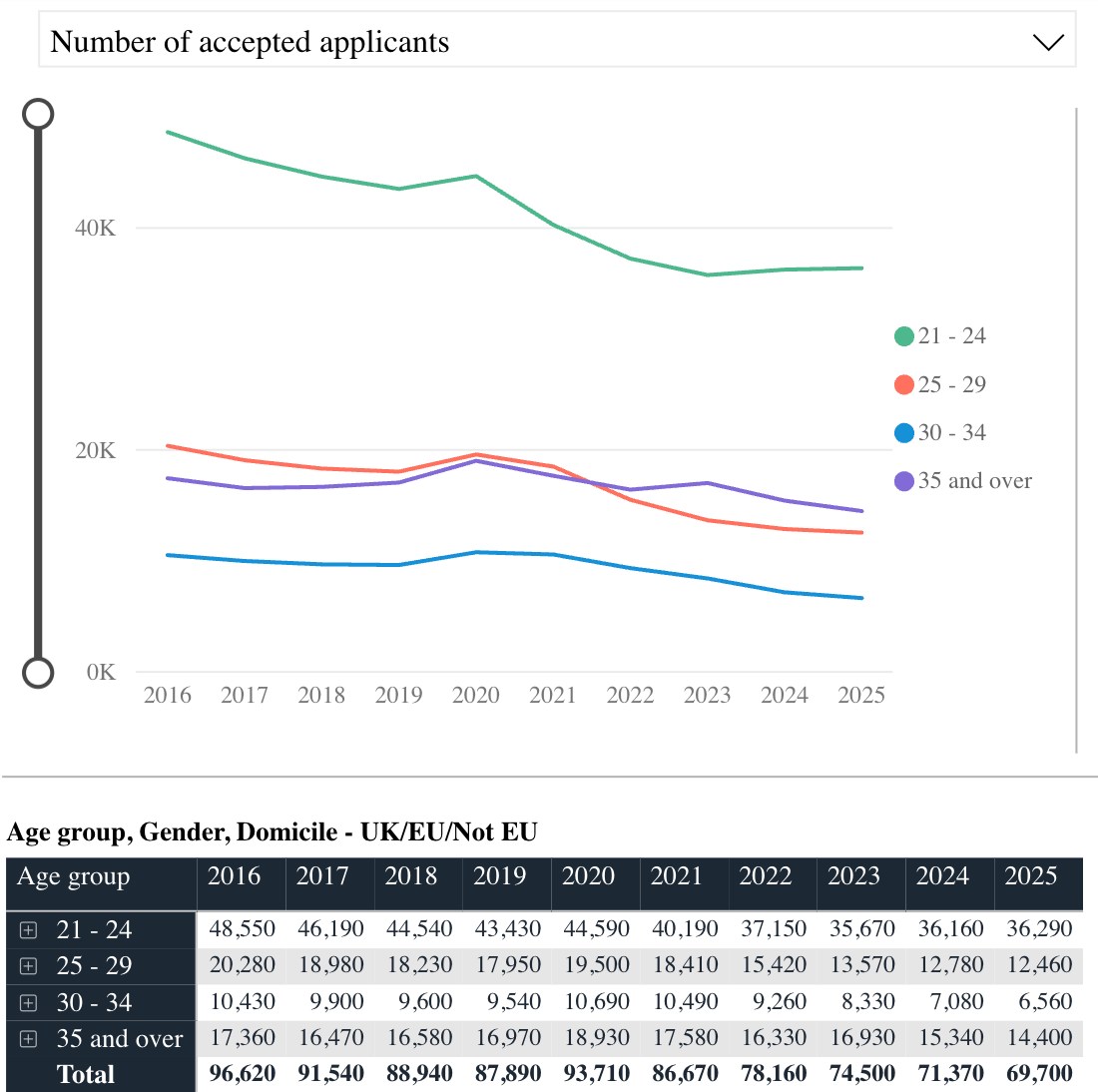

UCAS data on accepted applicants shows a pretty catastrophic mature student decline between 2016 and 2025:

- 21-24 age group: -25.3%

- 25-29 age group: -38.6%

- 30-34 age group: -37.1%

- 35+ age group: -17.1%

- Total mature students: -27.9%

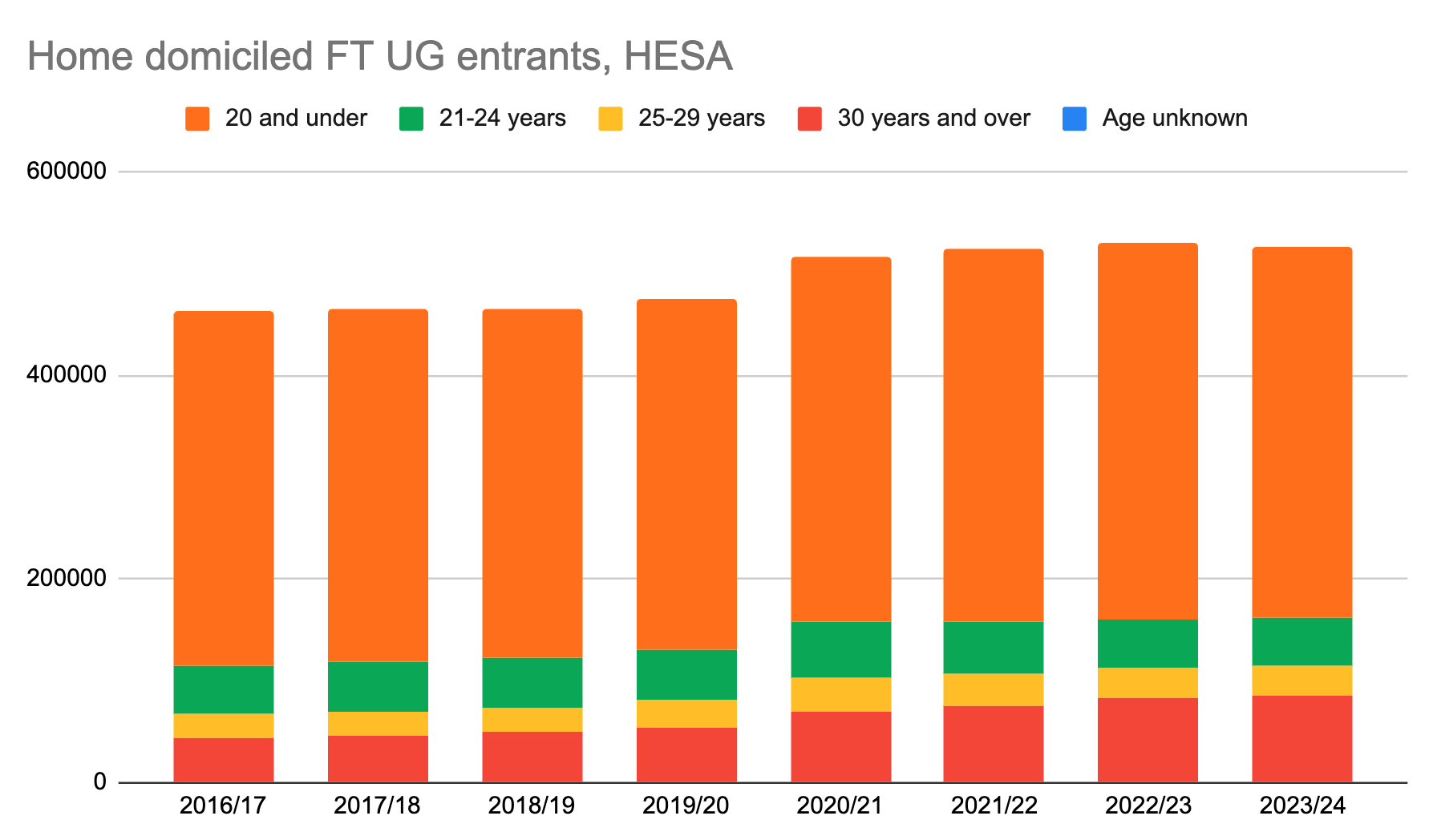

But HESA data on full-time (home domiciled) undergraduate entrants tells a completely different story for the period to 2023:

- 21-24 age group: -4.4% (modest decline)

- 25-29 age group: +27.0% (substantial growth)

- 30+ age group: +94.0% (explosive growth)

The 30+ figure is particularly notable – while UCAS shows this group declining by thousands, HESA shows it nearly doubling from around 44,000 to 85,000 annual entrants.

The modest decline in 21-24 entrants in HESA data suggests some people who historically would have attended university in their early twenties are now going directly from school instead.

Higher education entry rates among 18-year-olds peaked at 38.2 per cent in 2021, with nearly half of state school pupils starting higher education by age 25. The expansion inevitably reduces the population of “missed it first time” students who traditionally became mature students.

If roughly 15-20 per cent of those who didn’t attend university at 18 eventually became mature students, then increased youth participation could displace several thousand potential mature students annually.

That displacement effect operates primarily within the traditional UCAS system. See also the supposed decline in PT students – when students are routinely working 30+ hours a week and no end of providers market their “full-time” courses as “2 days a week, one from home”, we’re almost certainly seeing what would have been part-time students back in the day on full-time programmes.

Meanwhile the substantial growth in 25+ looks like a growth in non-traditional pathways, and actually suggests that overall adult learning demand is extraordinarily strong – it’s just flowing through different channels.

In other words, mature students are increasingly bypassing traditional university entry systems captured by UCAS, and pursuing higher education through direct applications, employer sponsorship, professional development programs, and alternative providers.

If anything, we’re seeing a bifurcation in adult learning. Traditional mature students – those in their early twenties who missed university initially – are declining in traditional systems but may be accessing higher education earlier instead. Meanwhile, genuine career changers and lifelong learners – those aged 30 and above – are entering higher education in unprecedented numbers through multiple pathways.

As such, the problem with the Lifelong Learning Entitlement is that it risks being designed for yesterday’s mature student patterns rather than tomorrow’s reality. If most adult learning growth is happening through employer partnerships, direct applications, and professional development rather than traditional undergraduate admissions, then policies focused on loading mature students up with debt via conventional university modules may miss their target entirely.

The growth in 30+ learners suggests that when adults have genuine reasons for returning to education – career changes, skill updates, economic necessity – they find ways to overcome existing barriers. The policy challenge may be less about removing obstacles and more about supporting and formalising pathways that are already working.

This doesn’t mean that nothing needs to be done. Specific sectors like nursing and teaching face genuine workforce challenges that require targeted interventions. Individual mature students still encounter real barriers that warrant attention. But there certainly seems to be no reason to panic.

There are about 40% fewer mature UK-domiciled entrants to undergraduate higher education in 2023/24 than there were in 2009/10 and a far lower mature student participation rate in England than in other nations of the UK. As well as being from a low base, the recent increase in students aged 30 and over you highlight was also almost wholly driven by students with non-UK nationality – many of whom are from a single European country – in franchised business and management provision. There has barely been any increase at all if you just look at British citizens, especially if you… Read more »

Turning anonymised data on the Franchise provision scandal into a good news story for the sector is certainly a very WonkHe take!