We spend a lot on HE. Or do we?

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

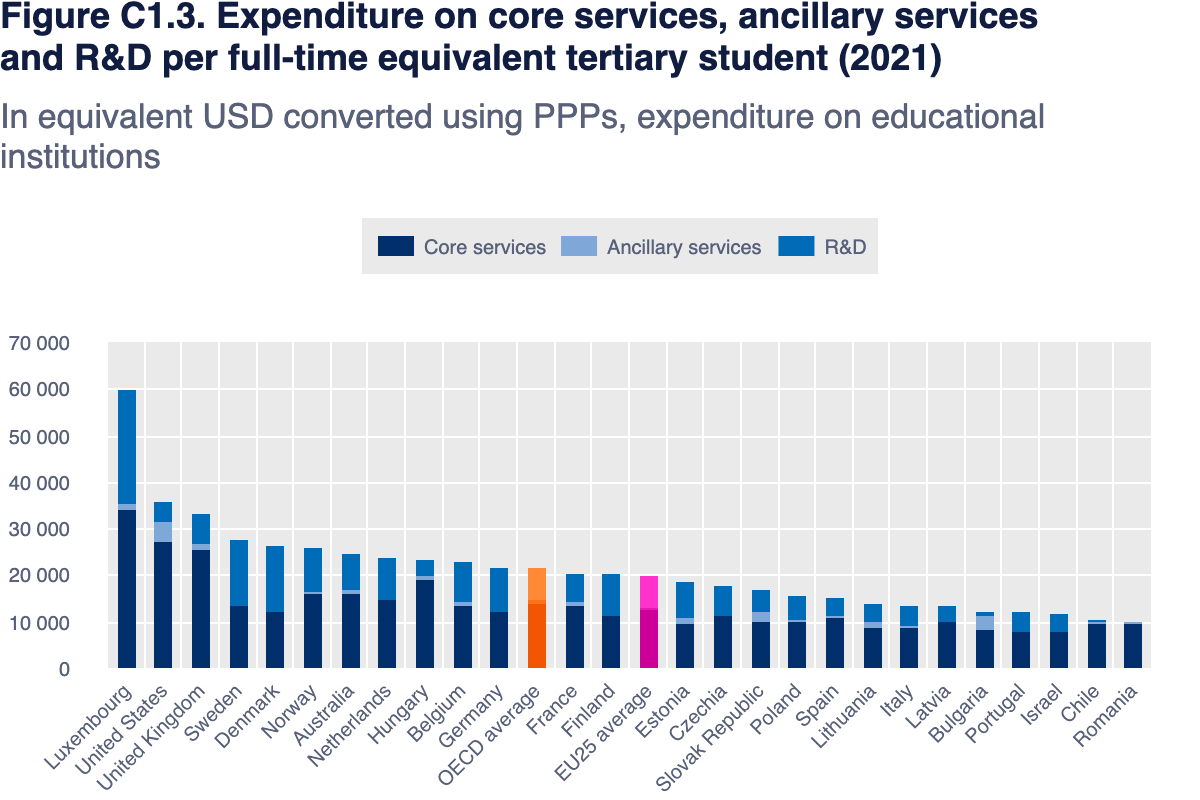

The chart that ought to strike fear into the heart of sector lobbyists in the report is this one, which suggests that the UK’s total expenditure per full-time equivalent student is beaten only by Luxemburg and the United States.

Even if you account for the figures being in dollars, I don’t think it feels like the sector is getting £25,669 per full-time equivalent student.

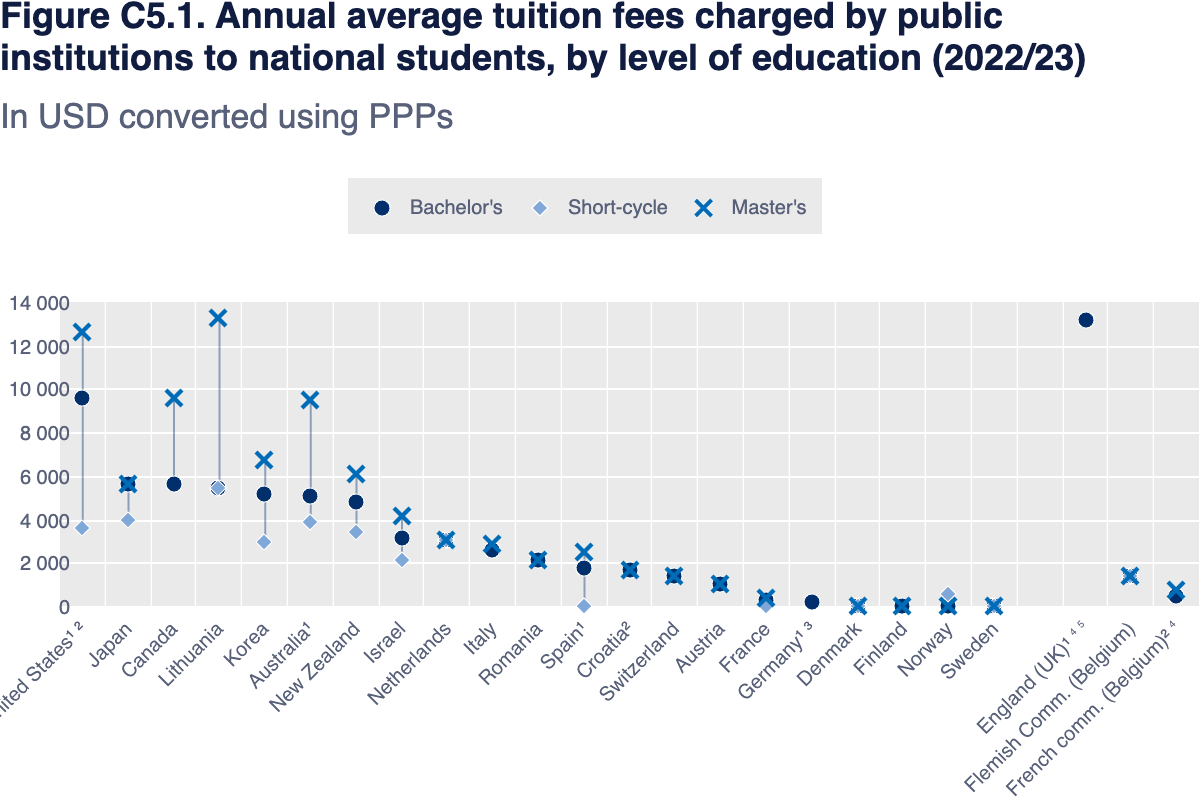

I’ve spent some time trying to work out the nature of the apparent discrepancy no to avail – and along the way have come across charts like this that can’t be right either:

It shows the annual average tuition fees charged by public institutions to national students, by level of education (2022/23), and that little dot in the top-right hand corner is supposedly England bachelors at £10,177 in pounds and pence. Eh?

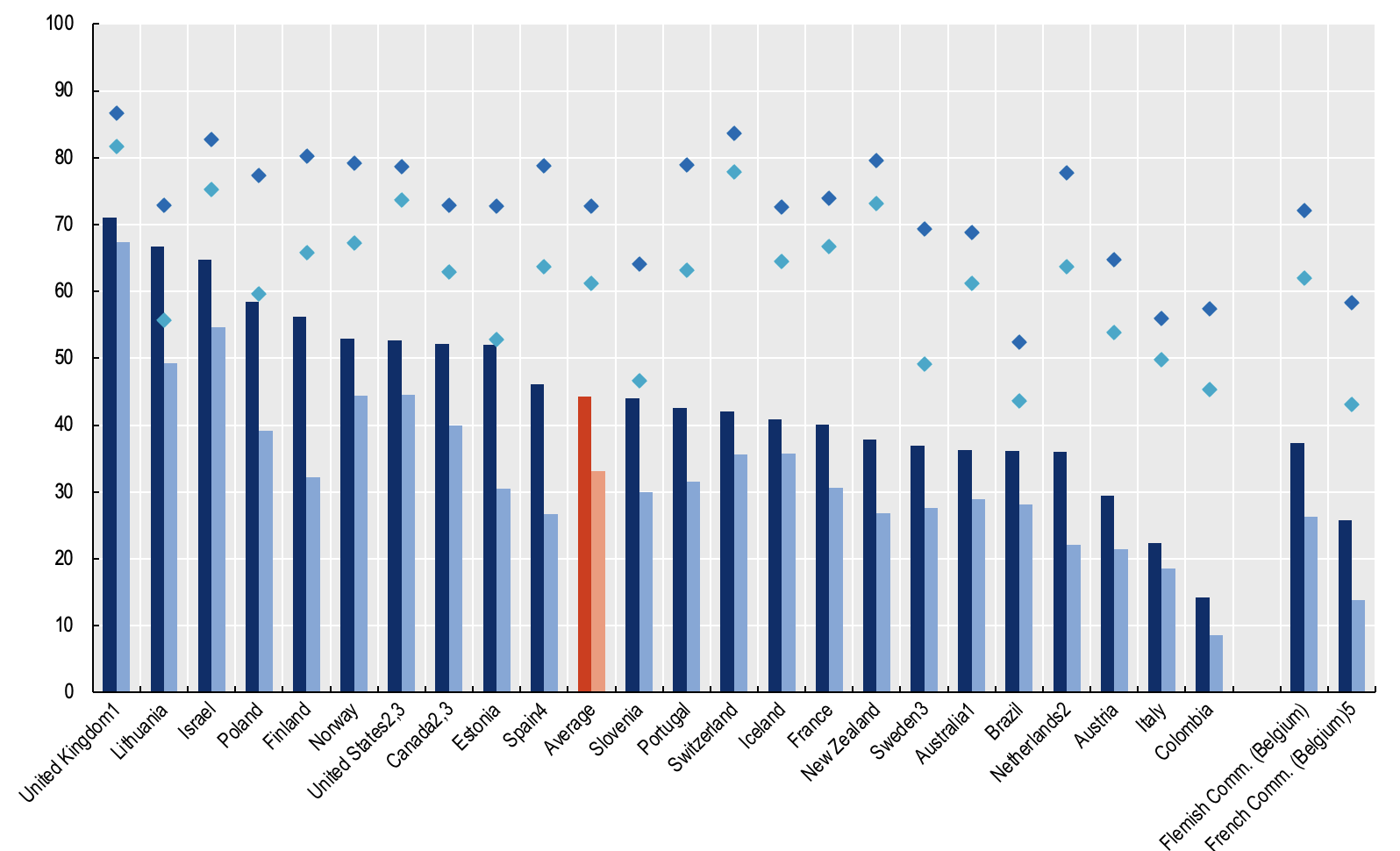

Even if we do spend more than most, these are figures per FTE per year – not the cost per cohort in total. And so it’s always worth reminding ourselves about this chart – completion rates of full-time students who entered a bachelor’s (or equivalent level) programme, by gender and timeframe:

The bars are men and women’s completion rate by the theoretical duration of the programme, and the diamonds are the completion rate when you add on three years.

In other words if our cost per annum is higher, then it’s partly a feature of ramming more students through, and doing so at top speed. Add on those three years and our completion rate looks like very similar to the Swiss.

If their undergraduates take roughly twice as long as ours to complete a degree, even if the numbers in that first baffling chart are right, the cost per cohort suddenly starts to look like an absolute bargain.

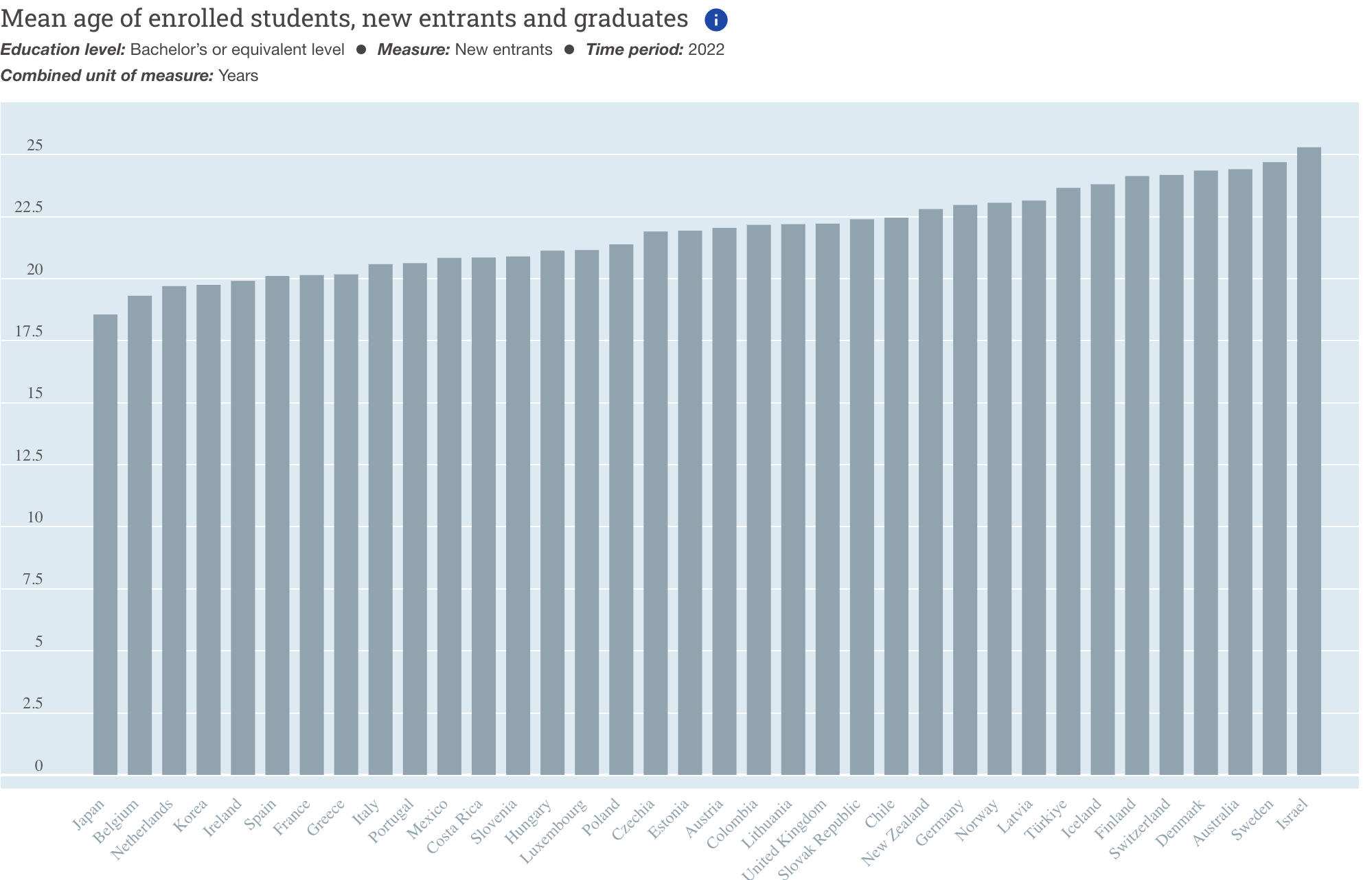

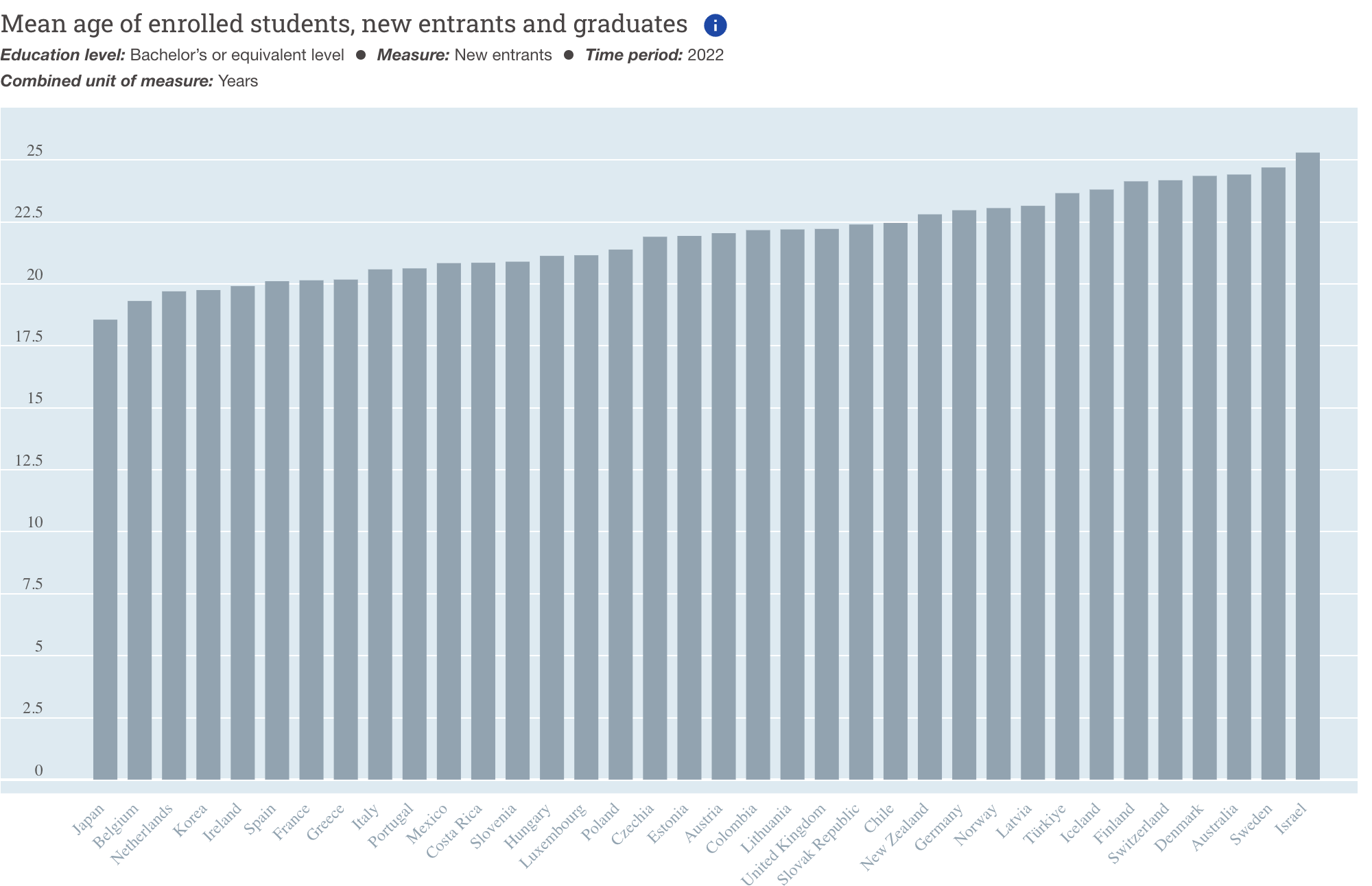

Do we ram students though at top speed though? We must do. Here’s the mean age of undergraduates on entry across the OECD. We’re in the middle of the pack on 22:

But here’s the distribution for the average age on graduation from a bachelor’s, which suggests we have the youngest undergraduate graduates in the OECD other than Japan, jointly with Belgium and the Netherlands:

That top speed thing might be curtailing the spend per cohort, but it can’t be doing anything for the mental health of students, studying in a system that is evidently hopelessly unforgiving of those that need to slow down, take a break or experience a setback.

And for all the incessant talk of Blair’s 50 per cent target, we do seem to be slipping behind on the share of the population with a master’s. This is the expected probability of graduating for the first time from a master’s before the age of 35 (men, the women chart is almost identical) if current patterns are maintained:

> I’ve spent some time trying to work out the nature of the apparent discrepancy no to avail Part of it is that the numbers are PPP figures, not a direct conversion to cash dollars. The PPP conversion rate in 2022 was $1 = £0.65, so $13,135 translates to average tuition fees of £8,538 per domestic student which sounds about right (most universities charge the maximum loan amount but there’s still a handful of institutions / courses that don’t) For the expenditure per student it looks like they might be taking total expenditure and dividing this by just the number… Read more »

…actually I think I’m partly wrong on my second point above, I don’t know why I thought they were separating out domestic students. The figure covers all students, both international and domestic – which will still be affected by the UK’s high proportion of international students (because they pay higher fees), but isn’t anything like as bad as I thought. For reference HESA data for 2021/22(*) says universities spent a total of £52.7 Bn while the student population was 2.86 Mn. That would be around £18,400 per student, or $28,800 in PPP dollars – so not too far off what… Read more »

Looks like it’s international and national, undergraduate and postgraduate. Masters degree fees would be included for example. It also includes government transfers to households for education. Not clear if that would include the costs of student loans for living costs or an estimate of amount loaned but not repaid?

Ten quick points 1. By my reading the U.K. is second in the chart on spend and not third any more. 2. Undergraduate degree lengths in the OECD are typically between 3 and 4 years and postgraduate frequently 2 years. 3. The longer times to completion for many students in these comparison with U.K. students is because a lot more fail or take credit which does not in the end contribute to their finally chosen program of study. 4. Years in education appears to be linked to higher earnings in the long run according to the Mincer equation, Jacob Mincer… Read more »

@Kevin P is even more correct than he claims. Looking at those same HESA years, if you look at FTE student population (2.3m) rather than total student population, then sector income comes out at £22,350 per FTE.

Convert that into the PPP $ the chart uses and it becomes over $34k per FTE.

So if anything, OECD data are slightly (by less than $1k I think) under-estimating UK income, not over-estimating it.