The more you work, the more you regret your HE

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

Now South Bank PVC Antony Moss and Advance HE’s Jonathan Neves have undertaken some follow up analysis to explore the patterns of work and study which students are now reporting – and there’s a cracking post up on the Advance HE website that details the findings.

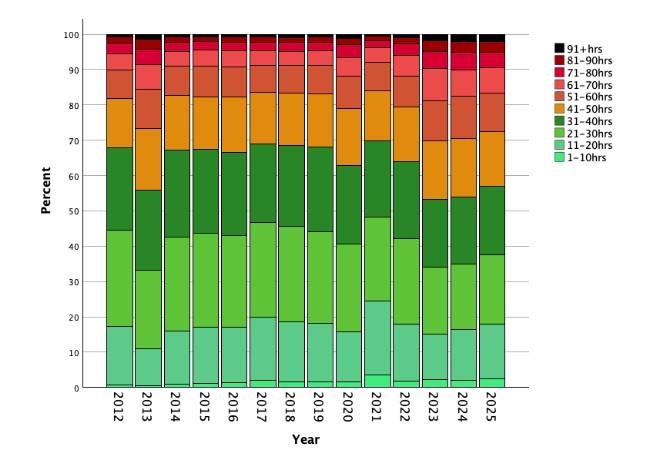

The survey captures reported hours in timetabled classes, independent study, and paid employment to assess total weekly commitments – and by analysing the distribution of the combined hours rather than just averages, they’ve uncovered how work and study commitments are creating unsustainable pressures on students, with big implications for their wellbeing, academic success, and future participation in higher education.

The most alarming finding from their longitudinal analysis of 2021-2025 data is that approximately 30 per cent of students now work and study for more than 50 hours per week, with around 18 per cent exceeding 60 hours weekly.

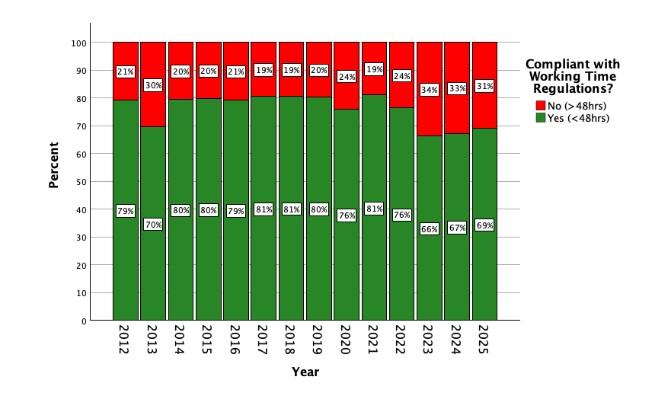

That’s a significant jump from previous years when only 20 per cent worked those sorts of long hours. To assess what constitutes “excessive” workload, they’ve applied the employment law standard of 48 hours per week as their benchmark – the same maximum used for apprentices balancing work and study.

Using that framework, the data shows that over 30 per cent of students routinely exceed what would be considered acceptable for employees in the workplace. The figures also exclude parental and caring responsibilities, meaning actual time pressures are even greater for the 15 per cent of students with such commitments.

What they’ve not factored in is getting to and from work. In our polling last year, we found that as the number of hours in employment went up, so did travelling time:

| Average PT work | Average travel pw |

|---|---|

| 0 | 3.4 |

| 1-10 | 4.4 |

| 11-20 | 6.4 |

| 21-30 | 7.1 |

| 31-40 | 7.6 |

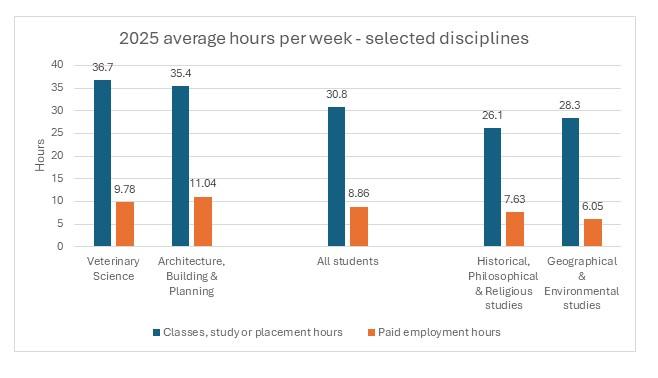

Via some subgroup analysis by academic discipline and course workload levels, Moss and Neves have also uncovered a counterintuitive pattern – students in the most demanding courses like Veterinary Science and Architecture also tend to work the longest paid hours, suggesting they can’t reduce work commitments even when academic workloads are highest.

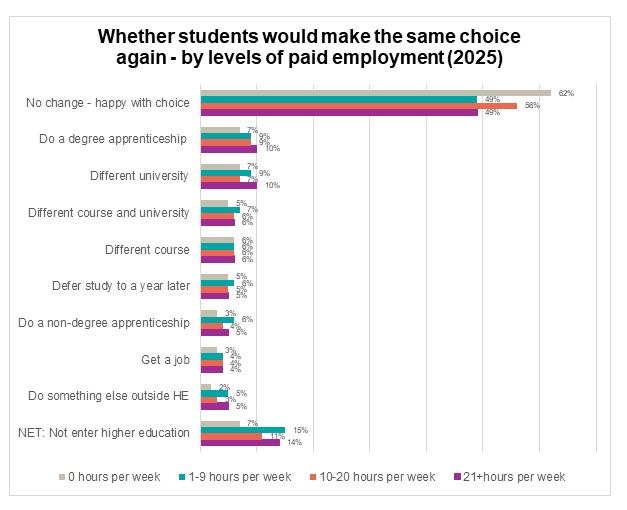

And when they cross-referenced work hours with student satisfaction data, they found that the pattern affects educational choices significantly – while only 7 per cent of students who don’t work would not choose higher education again, the figure doubles to 14 per cent among those working 30+ hours per week. Students in paid employment also show markedly higher interest in apprenticeships as an alternative route.

As well as forcing efficiency onto universities, we seem to have tumbled into making student life impossibly efficient too – rising living costs force students into excessive work, while universities have simultaneously increased assessment loads from an average of 4.6 per term in 2017 to 5.8 in 2025.

Of particular interest (to me, at least) is their comparison of actual student study hours against credit guidelines – students reporting studying 30-32 hours weekly is well below the notional standard of 40 hours per week (based on 10 hours per credit across 120 credits per year).

And there’s a danger in complacency. They assert that “UK students still achieve excellent outcomes by global standards”, but the assertion is linked to whether they complete or not.

That may be a false, and dangerous flag – and in PIAAC (international stats on proficiency in key information-processing skills among adults), our tertiary-education scores are slipping, with Czechia, Estonia, Switzerland, Austria, the Netherlands, Denmark, Flemish Region (Belgium), Norway, Germany, Sweden, Finland and Japan all out-performing us on adaptive problem-solving.

Moss and Neves recommend several interventions – increasing maintenance loans to meet the Minimum Income Standard for Students, reducing assessment loads and reconsidering modular assessment systems, revisiting assumptions about required study hours, and developing “Student Friendly” employer guidelines through Skills England partnerships (although the latter would be no substitute for our employment laws actually recognising students and/or the unpaid and exploitative nature of placements).

All good stuff – but as I noted here, we really ought to be using the flexibility promise of the LLE to revisit our pace assumptions as well.