The Home Office underestimated the impacts of the dependant ban – but don’t expect changes

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

A more detailed impact assessment had been produced for the changes affecting the student route – but was “still awaiting final Departmental clearances.”

And we’ve been waiting for it ever since – but the Friday between Labour and the Conservatives’ conferences seems to have emerged as a new “take out the trash day”, and two of the documents dumped were assessments of the spring 2024 immigration rules, and the 2023 changes to the student route and consequential changes to work routes.

Turns out that it was actually dated 13 July 2023 – which raises questions over why ministers were so keen for it not be “cleared”. Maybe it’s because the headline impact figure was that the government was estimating almost £5bn in lost tuition fees, and almost £15bn in lost tax revenues.

On these figures you might imagine that a new government keen on growing the economy might reverse the changes. Nobody is especially interested in reintroducing the ability for students to switch into skilled routes before completing – perhaps for obvious reasons. But what about that dependant ban?

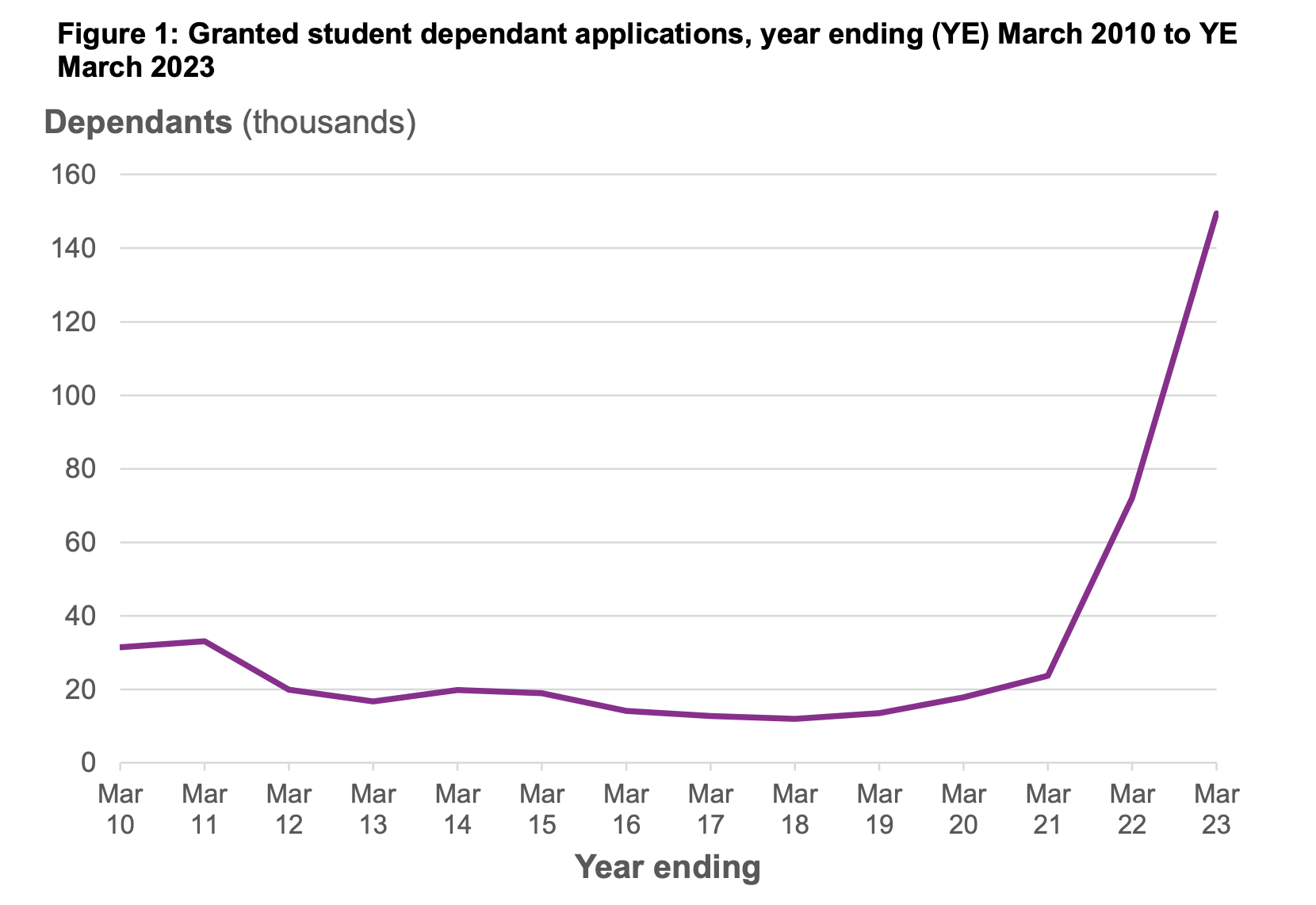

The rapid rise in dependant visas is a story we’ve told before on the site – if nothing else, the impact assessment for the change from the old “Tier 4” to the “student route” simply didn’t see dependants coming.

In this impact assessment, officials have written it up such that other ministers and newly re-appointed International education champion Steve Smith get the credit (or, depending on how you look at it, blame) for increase:

The nationality mix of students has changed considerably in recent years, with significant increases for Indian and Nigerian students. In June 2020, the Secretaries of State for Education and International Trade appointed Professor Sir Steve Smith as the International Education Champion. The Champion was appointed to help grow international opportunities for UK education. The International Education Champion set 5 immediate priorities reflecting where there is significant potential for growth and where the Champion could both open up opportunities and address barriers to that potential. India and Nigeria were a key feature of this work.

Students from India and Nigeria typically brought more dependants with them – in the year ending March 2023, around 73 per cent of visas issued to dependents of students were from the two countries. That represented a ratio of dependants to main applicants of 1.16 for Nigeria and 0.31 for India.

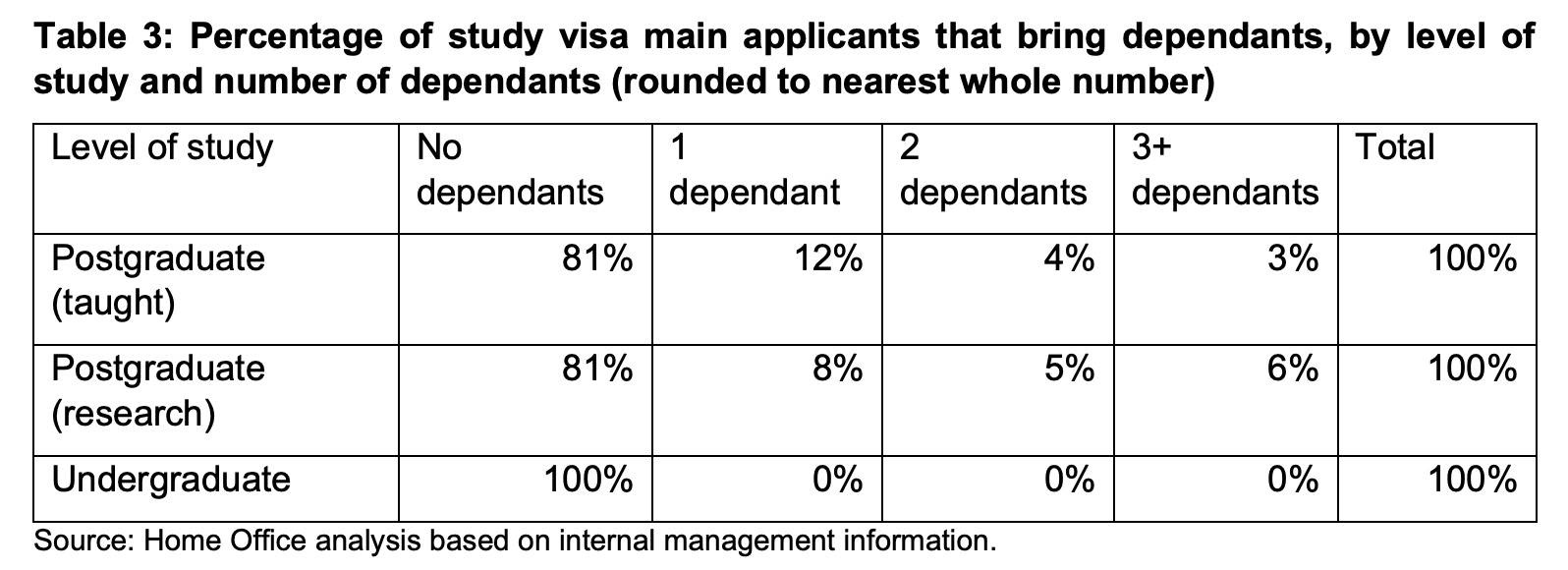

What we’ve not known – because the published figures have until now never told us – is how said dependants are spread. In other words, a small number of main applicants could be bringing very large numbers, or a large number of main applicants could be bringing one. That matters because you might reason that a ban on dependants might have a small impact on overall numbers of students in the former scenario, and a much larger one in the latter.

So this table is fascinating – because it simplistically suggests that international PGT numbers should “only” have seen a 19 per cent hit:

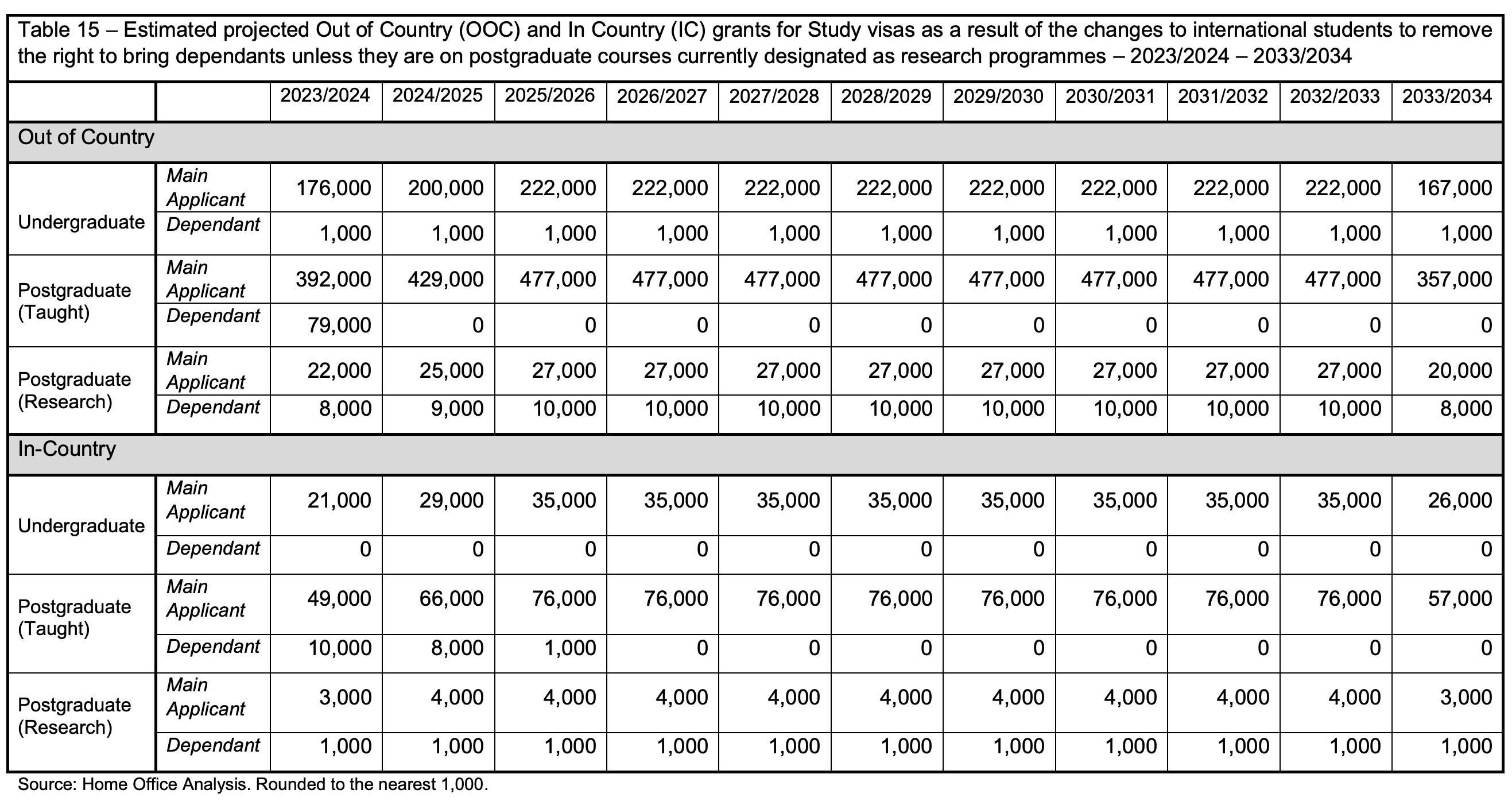

You then have to work out how long the course is, how many are likely to get onto the graduate route, how many might switch into skilled, and so on – and you end up with this “central estimate” table:

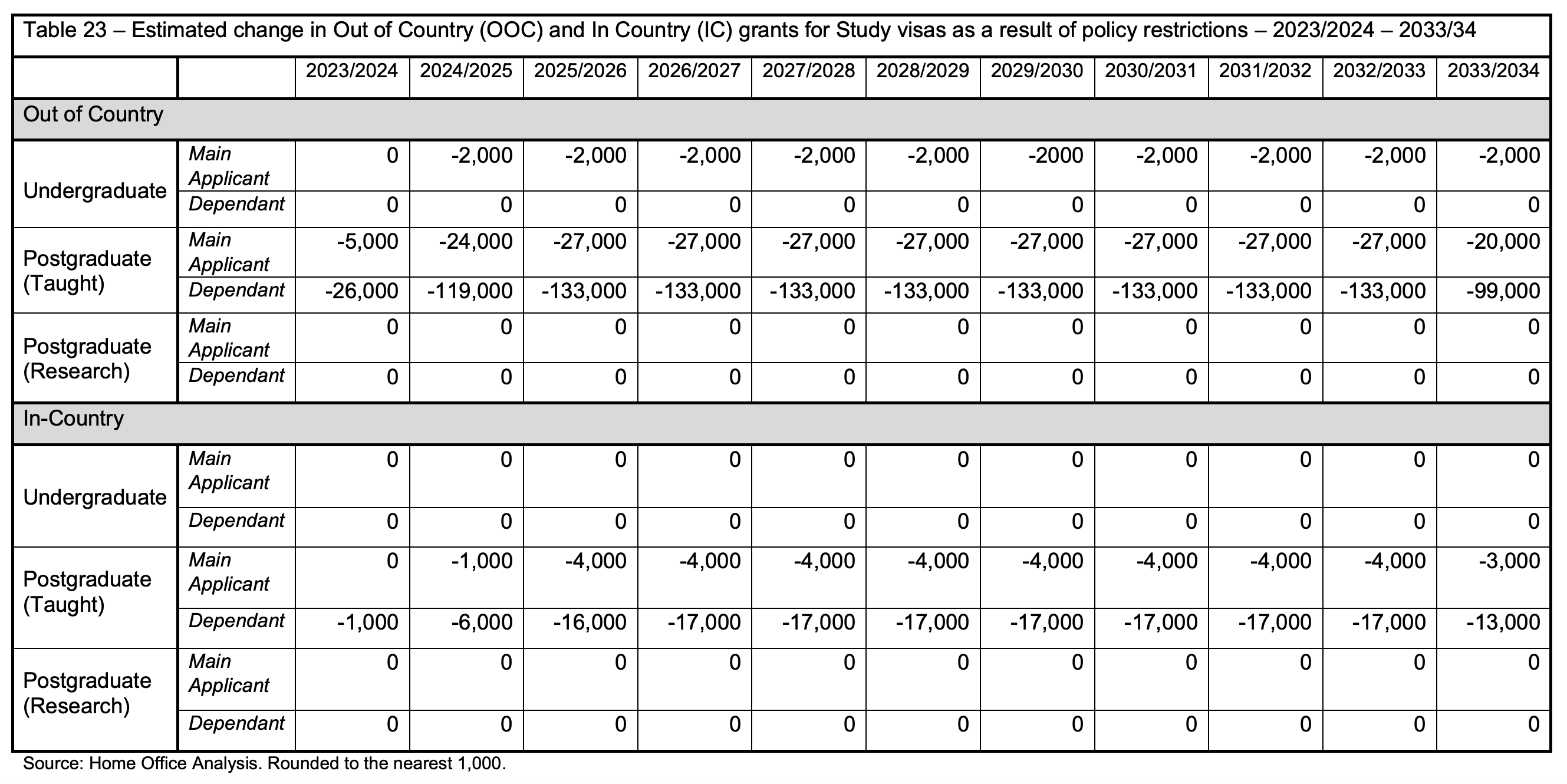

The impact assessment is now so old that we can already start to assess if officials were right. Here’s the change in visa grants that officials expected:

In reality in the three (quieter) quarters since we’ve had a ban on dependants, grants to main visa holders on PGT courses are already down 45k year on year. Extrapolate that drop into the crucial July-Sep quarter, and it looks like officials were out by about 53 per cent – almost 200k students.

In other words the projected economic impacts on the sector and the country were huge but hidden – and the reality is much, much worse.

That then all begs the question why – and if much worse than anticipated, whether there scope for reversal.

On the estimates being out, I have some degree of sympathy with officials. To get to these numbers they’re having to assess an astonishing range of unpredictables, all of which get multiplied together to compound those unpredictables.

(I should say here that utterly bafflingly, to get to its estimates the Home Office says it has “developed an experimental methodology” to assign course titles provided as part of visa applications to “derive” a level of study. It’s baffling because when requesting a CAS through the UKVI SMS, sponsors already have to provide a course level.)

The problem for those hoping for a lift on restrictions is that compound unpredictables is exactly the same issue that they’ve had in Australia and Canada – and pretty much precisely the reason those countries have moved towards controlling the outcomes (overall caps) rather than the various inputs.

Put another way – politically, a points-based system might make it look like you’re in control of the borders, but the unpredictable results mean that the only way to actually be in control is via a cap.

If we cast minds back to the International Education Strategy’s target of 600k students over ten years, the dramatically early reaching of that target was never supposed to bail out providers struggling with a freeze on dometic fees – and had that target had been met gently over that ten years, nobody would be batting an immigration eyelid.

And anyway, as this (and the original “Student Route”) assessment reminds us, even if officials were bang on, the inability of the department to estimate impacts on place or pressures on public services (school places being a biggie) also presents a major problem – one that also eventually points towards a cap rather than more rules relaxation.

Thanks for this analysis, it’s really interesting to see some of the highlights brought out like this. The assertion that officials were “out by 53%” does however assume that the reduction in student volumes we’ve seen are entirely attributable to these changes, and not wider global factors that could have reduced volumes below their historic peak – something this document does not try to assess. It would be interesting to pick students brains that chose not to come to understand what exactly drove that decision – as you point out only a minority were bringing dependants anyway! Also worth noting… Read more »