The graduate premium is falling. Or is it?

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

The argument in “Why is the average Graduate Premium falling?” runs like this:

Society shouldn’t stand back and allow what can only be described as a mis-selling of degrees on an industrial scale. The sector needs to cut the opportunity-for-all hype. The statistics agencies need to get their houses in order. And policymakers need to limit university places where they are helping no one but the university itself.

The case is made via starts like this: 160,000 of the UK’s 2024 student intake of 495,000 will earn around the same as or less than non-graduates:

But, unlike non-graduates, they will have their personal finances blighted by having to pay 9 per cent tax on earnings above £25,000 for decades. Many more will only achieve a very modest premium that will hardly justify the level of debt.

Fair enough. But in the report, increases in the minimum wage are ignored.

As the minimum wage rises, it lifts the “floor” of the labour market, which is bound to compress the absolute difference between graduate and non-graduate earnings, even if the relative advantage of a degree remains strong.

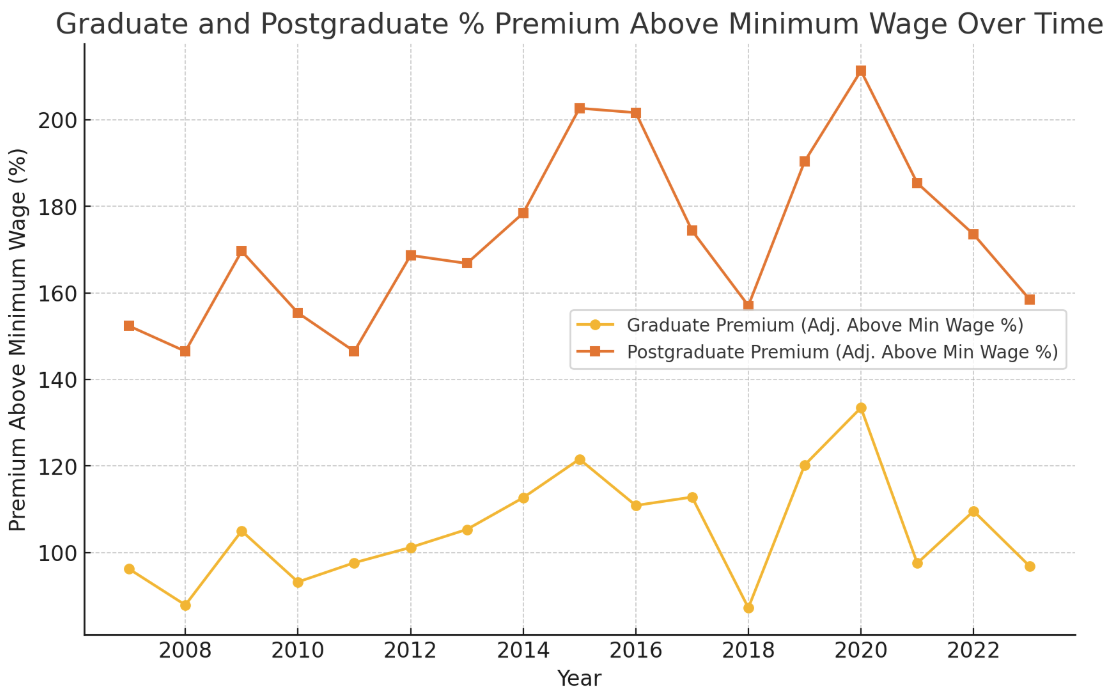

If we look at the premiums (21-30, Graduate, Non-Graduate and Postgraduate in England between 2007 and 2023) once we deduct the (maximum in terms of age bands) minimum wage from all three groups, the results look like this:

Wiltshire’s argument is that the graduate jobs market should adjust and continue to pay a graduate premium based on the value that it places on graduates “compared to largely unskilled non-graduates earning the minimum wage”.

That chart suggests it does. He goes on:

If the jobs market is only willing to pay graduates marginally above minimum wage (at least initially) then this is a real indicator of graduates no longer being so highly valued so it is assumed that this effect should remain in the model and doesn’t need to be adjusted for.

But here’s the thing.

If we consider the minimum wage as a rough proxy for a “basic living” standard (though that’s very much a simplification), the above chart tells us about the extra earning power a degree provides above and beyond that basic level.

It suggests that while the absolute gap between graduates and some non-graduates might be narrowing, the relative advantage of a degree, when measured against a basic living standard, has shown considerable resilience, and even growth (at least until 2020). Even with a rising minimum wage, a degree continues to provide a substantial financial “uplift” above that baseline.

If we think about why the minimum wage has been going up – it’s partly (this coming year in particular) about meeting people’s basic living costs. As such if the minimum wage used to be too low, you can argue that the graduate premium in the late 2010s was based partly on keeping non-graduates in poverty.

Nobody should be proud of that, and now as a society we’ve started to fix it.

But the problem is that the justification for the fees and debt model we have now was based on the usual way of looking at the premium – so when we rightly start to narrow the gap, you get Wiltshire’s report.

On the trad way of looking at the graduate premium, there was a justification of sorts for making graduates pay individually rather than taxpayers. If graduate skills are important to the economy and society, the real upshot of Wiltshire’s report is that the burden needs to shift back a little towards taxpayers.

Another way of looking at these issues is to think more strategically about the capabilities and skills we will need as communities in the future, rather than the individual financial rate of return on degrees and how enduring that might be. The next step is to think about whether the balance of government funded incentives and constraints support these societal needs. It seems likely to me that things will change further in the near future.M and probable that there will be constraints on inward migration to the UK outlined in the White paper due later this spring. These controls are… Read more »

Jim’s article ignores what it the main finding of my report. I discovered that the overall average Graduate Premium was falling because the average marginal premium fell to zero around 20 years ago when we increased HE% participation beyond 30%. My report calls for the Graduate Markets Statistics Data to no longer just report the overall average Graduate Premium but report it broken down by prior academic attainment so that we can get a handle of what are the outcomes for marginal candidates being added from lower prior academic attainment.

And Jim might want to have a look at my HEPI article when I analysed the fall in the average graduate starter salary compared to the minimum wage back to when the minimum wage was first introduced. It shows a dramatic drop. https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2024/10/25/the-fall-in-graduate-salaries-shows-the-argument-for-mass-entry-to-higher-education-has-failed/