The failure to fix university and student finances is Donald Trump’s fault

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

It says RPIX for Q1 of 2026 will be 2.8 per cent, down from 3.1 per cent.

That matters because most universities didn’t say “we’ll put fees up by the OBR’s projection of inflation”, they said “inflation”.

It’s almost certainly unlawful to say “we reserve the right to put fees up to the max the government allows in subsequent years”, and no university I’ve found yet says “we reserve the right to out your fees up by the OBR projection of RPIX on a given date” – partly because that would sound baffling, and the whole point is that consumers need to be able to predict the impact of price increase terms.

There’s an ongoing question of whether even saying “we’ll put them up by inflation” for continuing students is legal given higher than average inflation in recent years, which is why Ofcom have now all but banned in-contract price increases in telecoms.

There are a handful of universities I have on my list who have been saying “we reserve the right to put your fees up by inflation” for a few years, but appear to have now switched from using an actual measure of inflation at the point the increase was announced, to the 3.1 per cent prediction the government used when it made the UG regulated fee announcement last term.

There’s also a handful of universities whose terms said “we reserve the right to put your fees up by inflation” who have now published increases for continuing students that use two different rates of inflation depending on whether the fee for that student is regulated or not!

Both of those practices are… naughty – and text book “taking advantage of vulnerable consumers” as per the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024, due to be in force soon.

Anyway, even if universities had said “we’ll put your fees up by an OBR projection”, the projection has changed – so I assume at least for continuing students, universities up and down the land will be editing webpages to say £9,509 rather than £9,505 as we speak.

Will the max fee increase again in 2026?

The OBR’s forecasts that accompany budgets and fiscal statements have all sorts of baffling tables in them that talk about student loans.

They’re more complicated than ever these days because in the books, the Treasury has to guess how much will be repaid when a loan is made.

If I lend you a tenner, and I reckon you’ll give me £8 back, £2 is counted as (human) capital investment. Kind of.

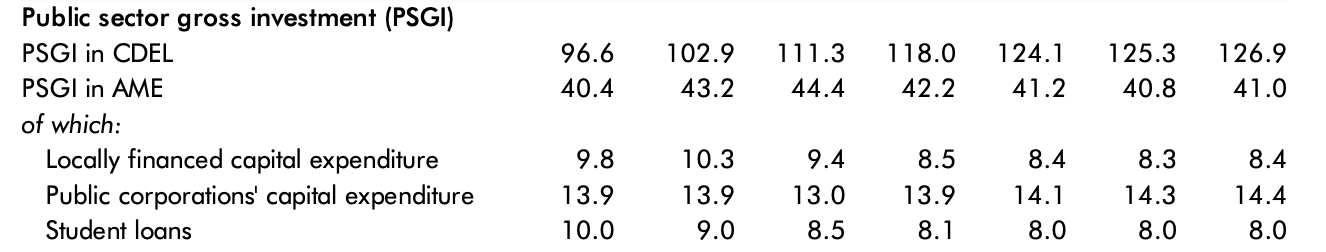

So when a table like this shows the Public Sector Gross Investment in student loans going down, that’s just a reflection of less being written off as Plan 2 borrowers disappear out of the system.

When we look at the other tables, the major question on many people’s minds is what sort of assumptions have been made – in other words, is there kremlinology to be done on stuff like the index-linking of fees.

Sort of. What the OBR does is project off ONS data and “current government policy”. So for example before fees went up, the reason we were fairly sure they would was because the “current government policy” of, say, this time last year was that the cap of £9,250 was indeed due to come off this September.

And that was reflected both in DfE’s summer publication and in the OBR forecasts, as DK explained on the site.

The max fee being unfrozen this year was, this time last year, government policy, so it got modelled. Ditto the foundation year (classroom-based subjects) cut. The new government just… implemented it.

That raises the question of whether the increase in the maximum fee to £9,250 is – in “official government policy” terms – a re-freeze, or whether DfE/OBR/HMT are assuming it’ll go up.

It’s hard to tell from what’s been published – the OBR’s outlay projections have increased since last October, but we can’t see what’s gone into the mix to build the gross cash spending on new loans figures.

The “good” news (sort of) is that the forecasts on the numbers of students entering have actually gone down, while the outlays curve up at a rate that doesn’t seem to be only about maintenance increases.

My thumb in the air would be that the OBR have used a DfE model that suggests the fee is to be index-linked, but we can’t quite tell. We’ll know more when DfE publishes its detailed forecasts in the summer.

There is one highly alarming thing to learn from ploughing through the tables, though.

What a drag

Buried in a tiny footnote in Table 6.8 of the OBR’s Detailed forecast tables Aggregates March 2024, there’s this astonishing bit of text:

In line with current government policy, the repayments threshold for postgraduates is assumed to be frozen until 2029-30. This assumption differs from DfE modelling.

It does indeed. Last summer DfE’s estimates were calculated as follows:

To enable future repayments to be forecast, for modelling purposes it is assumed that from 2025-26 the Plan 3 loan will rise in line with Office for National Statistics (ONS) average earnings growth statistics; there is no set policy for increases to the Plan 3 repayment threshold.

As I noted in February, if you were to search hard, you’ll have found that on 14th November of last year, the Department for Education (DfE) and Welsh Government confirmed the Postgraduate Income Contingent Student Loans repayment threshold to apply from 6 April 2025.

And guess what? It’s gonna be… £21,000. With no justification attached.

The upshots of that are significant next year. The median (young) graduate salary is now £35,000 and the minimum wage will be £25,397 as of April 1st (40 hours pw).

So the 6 per cent repayment rate for PG loans over the threshold will amount to £840 a year on the median (young) salary – and the undergraduate loan repayments at 9 per cent over the new £28,470 threshold will be £588 – or £1,428 a year.

That’s bad enough – but as I say, that footnote in the OBR projection “reveals” that the policy isn’t just to keep it at £21k this year, but until 2029-30.

That’s a fairly extreme bit of fiscal drag in the (graduate) tax system that’s going to hit PGs hard – many of them having already got into lots of personal debt to fund their PGT given the woeful state of the PG loan scheme.

Blame Elon

One other thing on loans that’s miserable. In January 2024 the IFS published an analysis of the impact of the cost of government borrowing on student loans.

That matters because when the government loans money to students for tuition fees and maintenance, it itself borrows that money.

That’s OK-ish when the costs of borrowing are low and when you’re able to hide the fact that plenty won’t repay in full – which is what George Osbourne was facing and doing when fees went to £9,000 and the number controls came off.

But now not only do the losses on the loan the government make have to be projected and recorded, the costs of borrowing the money to lend it out in the first place are through the roof.

In January 2024 the cost of borrowing as measured by the 15-year gilt yield had gone up from 1.2% to 4.0% over the previous two years – a three percentage point increase relative to expected RPI inflation.

Back then, that massive additional cost was not reflected in either of the government’s official measures of the cost of student loans – a loss of more than £10bn was not being captured in official figures, and still isn’t.

In the past, the government lost money on loans not fully repaid, but made a profit on those that are. Last year IFS said it was likely to make substantial losses on even those loans that are paid back in full, because the interest rate on government debt had gone higher than that charged on student loans.

Well guess what. Largely because German Chancellor Olaf Scholz is borrowing hard to fund arming up over Ukraine, Trump, Russia etc, our costs of borrowing here in the UK have risen higher still.

As of this week, the yield on the UK 15-year gilt now stands at approximately 5.07%. That’s gone up both since last year and since January – for instance, on February 27, 2025, the yield was 4.81%.

As I said back in February, the landlord of the Dickinson Arms used to be able to borrow money at low rates to buy stock, pay staff, and maintain the premises. He offered loans or credit to regulars who weren’t able to pay immediately, figuring that the low cost of borrowing made it a sustainable business model. He offered affordable pints and generous credit terms, confident that the costs of borrowing were lower than the rate of inflation.

But the cost of borrowing is up. Each barrel of beer bought on credit now costs him more to finance than it did before. He continues offering low-interest loans to his punters, but the true cost of financing is being hidden beneath the surface, gradually growing into a larger financial burden. And at some stage, the pub becomes insolvent – as does the company that owns the big block of student housing it can’t fill over the road because the Russell Group has been hoovering home students up the tables, and international students are choosing cheaper countries where more of their fees are spent on… them.

And not only are we borrowing money to lend out to tens of thousands of students to study boilerplate business courses out of barely converted office blocks in large urban areas as the owners and their sales agents trouser astonishing profits while profiting universities pretend they’re widening access, even if the students involved are real and did pay those loans back in full, we’d still be making a massive loss on them – which itself will be the backdrop to every meeting between DfE and HMT in the spending review.

You couldn’t (wouldn’t) make it up.

That’s the now even bigger problem the government faces over HE reform – which we can thank Donald J Trump for.