Students are a bit more woke than non-students. Chicken? Egg?

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

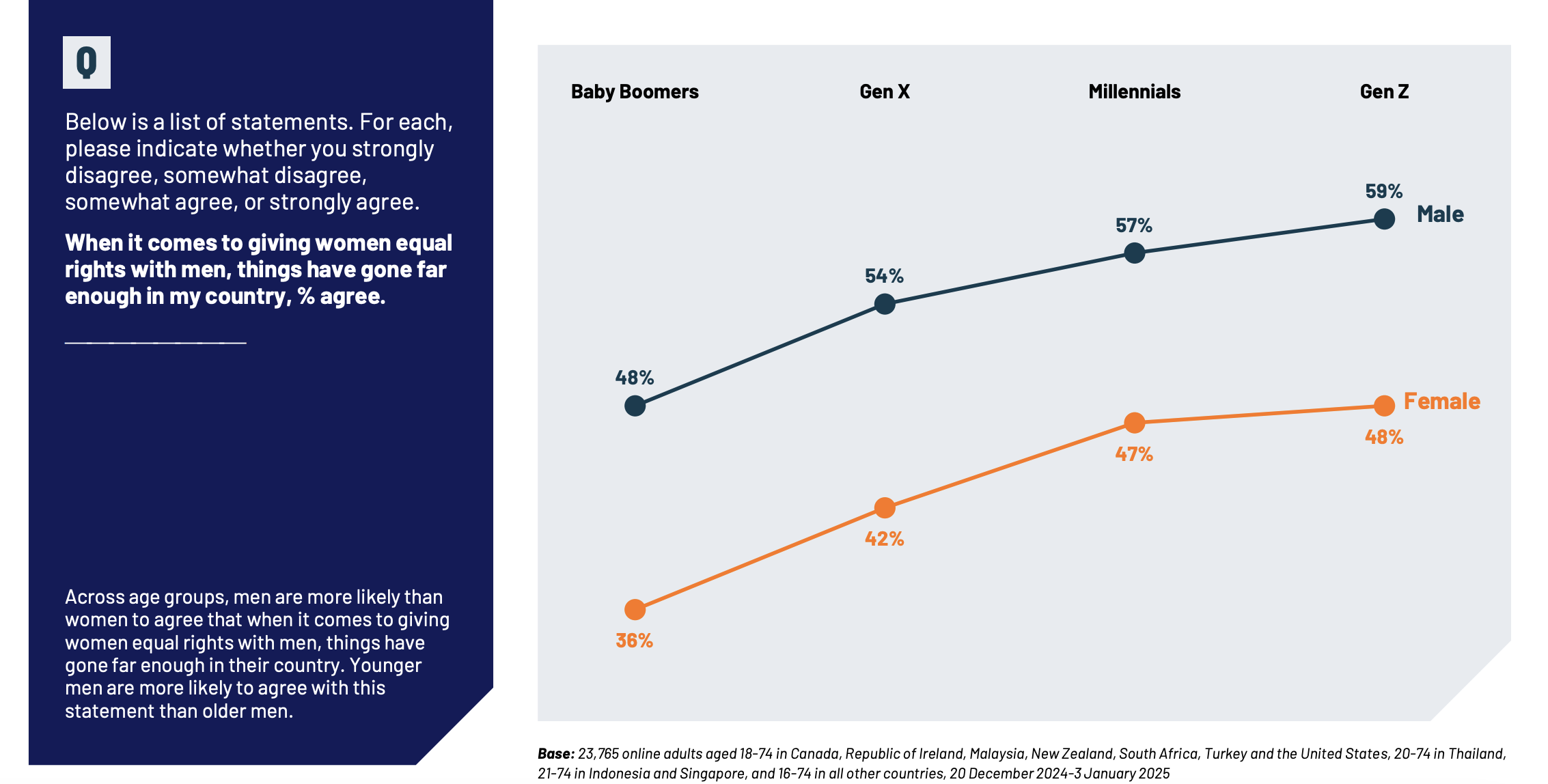

Maybe. Research carried out by Ipsos UK and the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership at King’s College London published last month finds that while younger generations are often thought to be uniformly “woke”, in reality the views of Gen Z men and women often diverge quite a bit – at least on gender equality.

It shows up a whopping 21-point gap separating Gen Z men and women on feminist identification (32 per cent versus 53 per cent) – a more gendered polarisation than any preceding cohort.

That fragmentation then extends beyond identity politics – nearly six in ten Gen Z men believe that equality efforts have gone “so far” that they now discriminate against men, compared with just 36 per cent of their female peers – what sociologists might term a “zero-sum fallacy”.

Worse, Gen Z men (28 per cent) are substantially more likely than Baby Boomer men (12 per cent) to judge stay-at-home fathers as “less of a man” – suggesting a big regression towards more rigid gender expectations among younger males.

Even if you ignore the gender differences, Gen Z as a whole perceives significantly more gender tension in society than older generations. 59 per cent of Gen Z acknowledge tension between men and women, while only 40 per cent of Boomers share this perception.

Don’t panic – those are global findings. Britain ranks reassuringly low (26th of 30 countries) for perceived gender tension, outperforming both Australia and the United States. And fewer Britons – particularly men – believe that stay-at-home fathers are “less manly,” dropping from 28 per cent to 13 per cent in just one year.

What about students

Most polls like this, of course, don’t separate out students from non-students, but a new report from the University of Glasgow’s John Smith Centre – Youth Poll UK – does.

It used UK pollster Focaldata to poll young people’s attitudes and priorities, and it also carried out in-depth conversations with young people aged 16-29 across the country.

On immigration, students and graduates are substantially more positive, with 63 per cent agreeing that immigration improved their community compared to only 43 per cent of non-students holders – a 20 percentage point gap.

There’s also a notable difference in views on other “woke” issues. Students show higher concern over racism (77 per cent vs 69 per cent), greater acceptance of concepts like toxic masculinity (71 per cent vs 60 per cent), and are less likely to view feminism as harmful (13 per cent strongly agree vs 20 per cent for non-degree educated).

Although you’ll note that on all four of those “woke” issues, non-students all show a substantial majority too – maybe lefty teachers in schools did it to them.

Community identity formation differs markedly between the groups too. Students and graduates identify more through workplace connections and political affiliations, while those without degrees find their identity primarily through family and friendship circles.

Counterintuitively, if you read the press and believe the twaddle about HE teaching students to hate their country, students also feel more connected to their neighbourhoods (64 per cent versus 56 per cent) and to the UK as a whole (61 per cent versus 55 per cent).

That challenges childish narratives about educated “citizens of nowhere” – instead suggesting higher education may actually strengthen, rather than diminish, geographical belonging.

The data also shows students identify their most pressing national concerns as climate change, inequality, and corruption, while non-degree holders focus on immediate economic pressures and crime – students appear more focused on systemic, long-term challenges.

Meanwhile students report being “very happy” at rates 7 percentage points higher than their non-student counterparts (22 per cent versus 15 per cent) and experience daily anxiety significantly less often (21 per cent versus 30 per cent). The nature of anxiety differs markedly too – students worry about career advancement and job security, while non-students struggle more with immediate financial concerns and family pressures.

There are huge dangers in over-interpreting this sort of stuff because of the vast differentials in who gets to go into HE – much of the above could be a signalling effect, rendering the results as problematic as those underpinning notions of the “graduate premium”.

But notwithstanding that crowing about the above will wind up some, faced with a choice between twiddling on about lifeline salary advantages versus health, happiness and social attitudes, I know what I’d choose when promoting HE.

Oh – and students are less likely to support justifiable violence (57 per cent agree versus 65 per cent for non-students) and more likely to take a holistic view of systemic problems, with 53 per cent blaming both political and economic systems equally.

On young people generally, the report fuses focus group findings with the polling to suggest three approaches to young people – avoid negative stereotyping of Generation Z; develop more honest and constructive political discourse that prioritizes fundamental needs like job security, quality housing, and effective healthcare; and actively engage young people who feel voiceless.

The country’s political parties appear to have fundamental differences on all three of those approaches re young people in general, and on students specifically. Maybe that explains the differences in political polling.

Students have substantially higher political trust, with 76 per cent believing their vote shapes both local and national futures – compared to just 60 per cent for non-students holders.

Students and graduates are also significantly more likely to consider getting involved in politics (46 per cent versus 31 per cent), suggesting higher education correlates with – or perhaps engenders – greater confidence in your ability to effect political change.

Both groups similarly believe politics is too divided, but students and graduates view political involvement as more honourable.

Voting intention figures show the biggest divides, and maybe that’s why parties paint students in particular ways – or take them for granted. Students and grads support Labour at rates 16 percentage points higher than non-degree holders (39 per cent versus 23 per cent) and are far less likely to abstain from voting entirely (9 per cent versus 20 per cent).

Support for Reform UK shows the opposite pattern, with non-degree holders 5 points more likely to back the party. Conservative support remains nearly identical (and tiny) between both groups, while Green and Liberal Democrat support sees modest increases among students.

The figures reinforce that well-rehearsed idea that education level is becoming a primary electoral cleave in British politics. But maybe it’s more the attitudes of parties and politics than the teaching of woke academics that’s causing it.