Student loan interest will rise to 12 percent

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

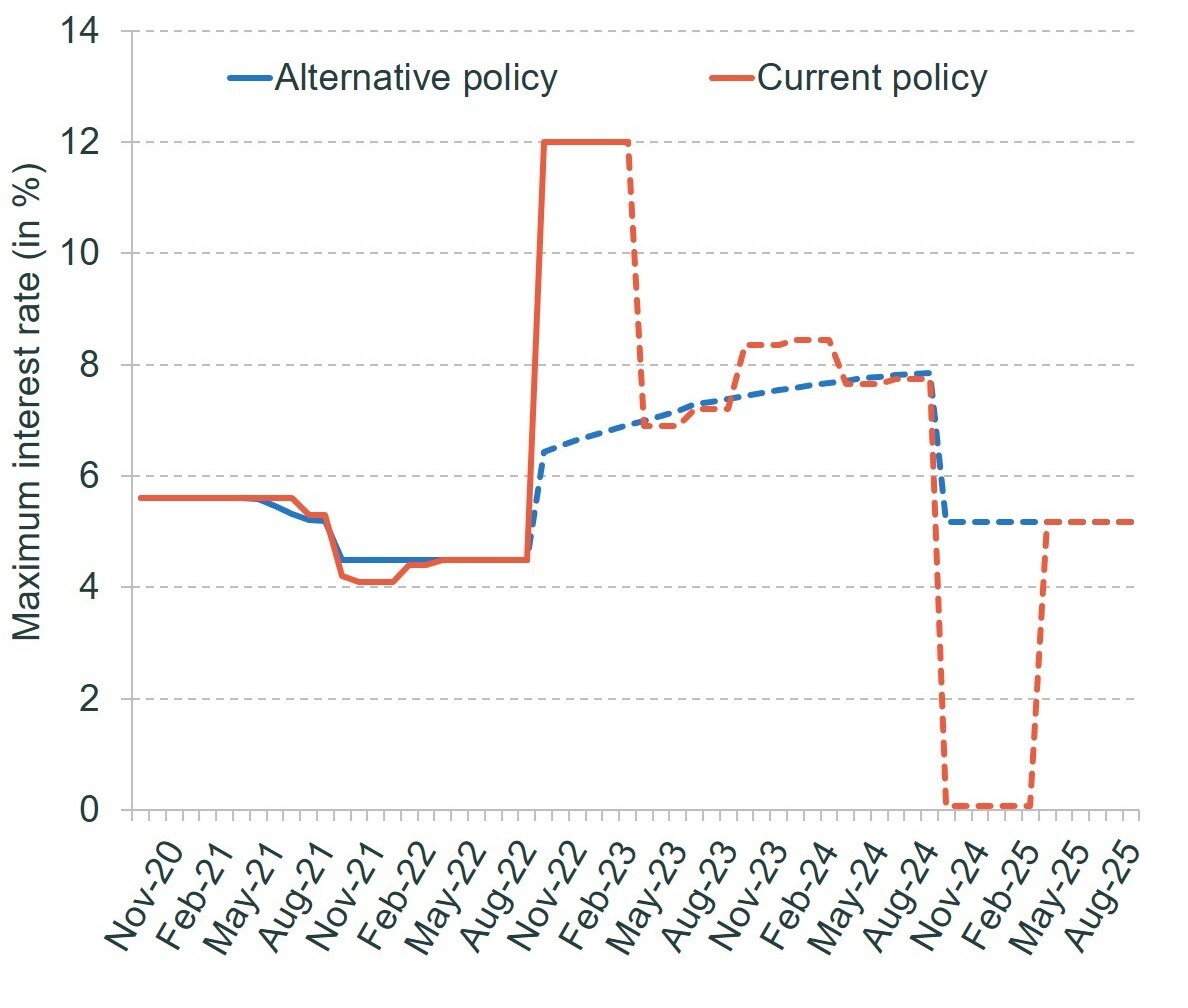

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) announcement that inflation for the year ending March 2022 was 9 percent means that the maximum interest rate for Plan 2 (ie post-2012) borrowers – charged to those earning more than £49,130 – will rise from its current level of 4.5 percent to 12 percent this autumn. Rates for low earners will rise from 1.5 percent to 9 percent.

That will mean that if they have a typical loan balance of £50,000, a high-earning recent graduate would incur around £3,000 in interest over six months – more than someone earning three times the median salary for recent graduates would usually repay during that time.

It’s all explained in a new observation note from IFS’ Ben Waltmann, who notes that the increase will mean borrowers are being charged more than average mortgage rates, and more than many types of unsecured credit. Of course, mortgages and many types of unsecured credit don’t generally offer income contingent repayment terms or get written off after 30 years – but it will still feel bad when folks look at the principal figure in the bottom corner of their annual loan statement.

Why a rollercoaster? The increase will actually only last six months – the law says that student loan interest is not allowed to rise above interest rates “prevailing on the market”, and the Department for Education (DfE) implements this by placing a cap on loan interest at the average interest rate on unsecured commercial loans – the latest Prevailing Market Rate being February 2022’s 6 percent.

The problem is that there’s a six-month lag between interest rates exceeding the cap and the rate actually being reduced. As Waltmann notes, it takes two months for market interest rates to published by the Bank of England after measurement, then DfE waits until student loan interest rates have been above the cap for three subsequent months before it adjusts them downwards by the three-month average amount by which the cap was exceeded, and then there’s a two-month implementation lag between DfE acting and the interest rate being applied to borrowers’ accounts.

That all generates this daft looking graph, which basically shows us what happens when you have a policy designed for very slow and gentle changes in inflation responding to sudden and rapid changes.

In some ways it’s a version of the rollercoaster that is set to apply to student maintenance loan increases – which for some reason uses a different version of RPI and a different, much older calculation of it. We looked at that on the site here.

The Department for Education’s press quote is quite funny. First of all it points out that student loans are not like normal loans:

Unlike commercial loans, student loans are protected in a number of ways. Monthly repayments for student loans are linked to income not to interest rates, or the amounts borrowed, and borrowers earning below the relevant repayment threshold make no repayments at all. The IFS report makes it clear that changes in interest rates have a limited long-term impact on repayments, and the Office for Budget Responsibility predict that RPI will be below 3% in 2024.”

And then it goes and spoils it all by saying something stupid like:

Regardless, the government has cut interest rates for new borrowers so from 2023/24, graduates will never have to pay back more than they borrowed in real terms.”

So if interest rates going up aren’t much a problem, why are you cutting them in the future?!?!

Much of Twitter naturally grasped the wrong end of the stick, and only noticed the climb in the coaster rather than the dip. If you think about it, if you’re a new or recent graduate and loan balance is still rising, you actually benefit from the delayed cap – because interest rates will be high when your loan balance is low and low when your balance is high.

But in truth most of it makes barely a jot of difference in general.

The thing to remember about student loan interest is that it was never really about interest per se. It was a way of making higher earning graduates pay more, while the maximum term and repayment threshold ensured that lower earning graduates paid less. It was a mechanism that delivered a degree of progressivity, even if nobody ever understood that.

Set aside the fact that some are so rich they never take out a loan. Before the recent temporary freeze to the repayment threshold, IFS was saying that around 80 percent of graduates won’t pay off in full. That will have gone down a bit thanks to that temporary freeze, but in reality interest rate rises only really make a difference to those in the very highest lifetime earnings categories – which is what makes DfE’s decision to go for no “real” interest on loans for new borrowers so outrageous – it’s a big saving for the richest (mostly male) grads.

I can (and have in the past) made a decent argument for student loan interest to be at 1000% – then it’s a straight graduate tax for X years, stops the richest from paying off early and you put the savings into maintenance support and the unit of resource.

Waltmann reflects a regular Martin “Money Saving Expert” Lewis concern and says that current borrowers may spend large sums on paying back their student loans early to avoid high interest rates, unaware that they will be compensated by lower interest rates later or even that their loans will be written off with no adverse consequences after 30 years.

He also says that some prospective students may be put off from going to university altogether – something that HEPI’s Nick Hillman disputes when he says that the much higher level of inflation is unlikely to put school leavers off applying to university:

Every major change to student finance in England in the past 30-odd years has been predicted to put them off, but application rates have kept on growing.”

I’m much more concerned about the fact that students are set to experience the largest-ever drop in living standards this September, with a real-terms cut to the value of maintenance loans of 7 per cent. I’d also be more concerned about the deterrent impacts on postgrads – although again, I’m much more concerned at the failure to uprate the PG loan by inflation this year, or by the above-inflation increases that universities have been applying to PG fees.

A good example of the distortions here is the focus on Plan 2 borrowers. Plan 1 borrowers and those in Scotland have the interest on their loans index-linked too. But because their balances are lower and they’re more like a loan insofar as they are designed to be paid off in full, average graduates really will be more likely to have to pay more back.

The problem, I think with the IFS note and the huge volume of commentary and coverage it has generated, is that the IFS has the principal aim of “better informing public debate on economics in order to promote the development of effective fiscal policy”. But it appears to have achieved the opposite here.

The Telegraph headline screams “More than a million graduates stung by £3,000 stealth student loan raid”, only to admit twelve paras in that “it is not clear how many graduates will be affected by the change.” Bloomberg says that rising inflation points to “crushing student debt payments ahead” when payment levels won’t be impacted. And an op-ed in i News first points out that only around the richest fifth of graduates will ever pay their loans off, and then in the next paragraph terrifies everyone by saying that “typical graduates will see their student loans rise by £3,000”.

It’s not helped by the campaigning bodies. UCU general secretary Jo Grady worries about subjecting graduates to the “whims of volatile markets and rocketing interest rates”, and says the news will leave those already repaying their student loans “preparing for increased debt payments during a cost of living crisis” which is at best disingenuous. Meanwhile on BBC News NUS President Larissa Kennedy said that “What is abundantly clear and incredibly true is that this change, this astronomical rise in interest rates, which is going to up to 12 percent, is going to hit the lowest earning graduates the hardest”, even though that is neither abundantly clear nor incredibly true.

They might think they’re working towards student debt abolition, but they may also be encouraging everyone to think that interest rates hit average graduates – which then, ironically, generates pressure on the government to reduce them, a change that only benefits rich gradates and causes wider pressure to reduce the unit of resource, preventing improvements to maintenance.

As such, while the Tories are settled in on a new status quo and the Lib Dems hide under some coats until it all goes away, there’s an interesting battle coming soon here when it comes to Labour policy. It’s hard to believe that a Starmer-led party will be promising free education, but there’s then choices on fee levels, interest rates, term length and grants v loans for maintenance. If your choice is between something that sounds good but turns out to be regressive, or something that is progressive but sounds bad when you announce it, what do you do?

As I say, it’s all a terrible mess. We could do with a big review of it all, to be honest.