Sometimes DfE has to say the quiet part out loud

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

This is because a 15.5 per cent increase would be required to maintain the value of loans and grants for living and other costs in real terms using the 2020/21 academic year as a baseline (as measured by CPI) due to the recent spike in inflation.

Therefore a 2.5 per cent increase in maximum support for 2024/25 may not restore the erosion in purchasing power since 2020/21 and is unlikely to prevent a further erosion in purchasing power by the start of the 2024/25 academic year.

It’s not NUS, or Save the Student, or the Sutton Trust, or the Russell Group, or Universities UK, or the IFS or even me saying the above. It’s the actual Westminster Department for Education.

There was a time when DfE’s Equality Analysis of its annual changes to student maintenance would get published alongside those changes.

You can see why. Back in 2020, for example, the document was able to reason that by increasing the maximum level of support available in line with forecast inflation, it would ensure that students do not suffer a real term reduction in their income:

This means they should be able to make the same spending decisions as they did previously with regards accommodation, travel, food, entertainment and course related items such as books and equipment, the costs of which will also have been rising over time.

That argument was always a bit naughty, given the analysis never took into account that as well as prices rising, incomes were gently rising too. And so in a system which starts to reduce the amount of support for students once the household they’re from earns over a threshold that hasn’t changed since 2007, even matching inflation would still result in reduced spending power.

But in the past few years, DfE has both given up publishing alongside, and civil servants have given up trying to frame changes positively. Hence this year’s analysis was slipped out late afternoon on Friday, and aside from a gouged in para on the £10m that Robert Halfon has found to prop up hardship funds and mental health, it’s bad news all round.

Some of the text survives from year to year. So for example the “rationale for student finance” remains that if we didn’t loan some money to students for their costs:

…only those students who would be able to fund the upfront costs of their studies through private means (e.g. personal savings or income or commercial borrowing) would be able to participate in higher education.

And so in terms of annual changes:

…increasing the maximum level of student support available across these different streams of funding in line with forecast inflation aims to ensure that students do not suffer a real reduction in their income.

But – as others have been pointing out for a few years now – the practice of basing those increases on Office for Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) projections of RPIX inflation to deliver the above principle now means that the department is conspicuously failing to deliver on its own policy:

…Due to the recent spike in inflation, the latest OBR figures for RPIX published in November 2023, show an outturn figure for the first quarter of 2023 of 12.7 per cent (compared to the 2.3 per cent forecast figure used for increases to support in 2022/23) and a 5.2 per cent forecast figure for the first quarter of 2024 (compared to the 2.8 per cent forecast figure used for increasing support in 2023/24).

This means that increases in maximum loans and grants for 2022/23 and 2023/24 have not maintained their value in real terms. A 21.6 per cent uplift in 2024/25 would be required to maintain the value of maximum loans and grants for living and other costs in real terms as measured by RPIX using 2020/21 as the baseline and a 15.5 per cent uplift would be required as measured by CPI.

Of course student finance is (partially) devolved in a way that benefits, state pensions and the minimum wage are not. And while there is often sleight of hand in the way that “inflationary” increases apply in those areas, there’s no rationale that’s been as egregiously incorrect in the support that governments offer other low income groups as what’s been happening to student financial support.

Hence the equality analysis has to admit that the headline 2.5 per cent increase “will not provide any catch up of the real terms losses already seen by students” due to high inflation.

And it feels the need to point out that last year half of students felt they had financial difficulties, a quarter had taken on new debt in response to the rising cost of living, and that many students will not be able to make the same spending decisions previously on accommodation, travel, food, and course related items such as books and equipment – the costs of which will have been rising over time.

Included in the document is a rehearsal of some of the differences between the Retail Prices Index (which, minus mortgage interest, is called RPIX and is the projected OBR rate that DfE uses) and the Consumer Prices Index – which is widely regarded as a more helpful and accurate measure of costs.

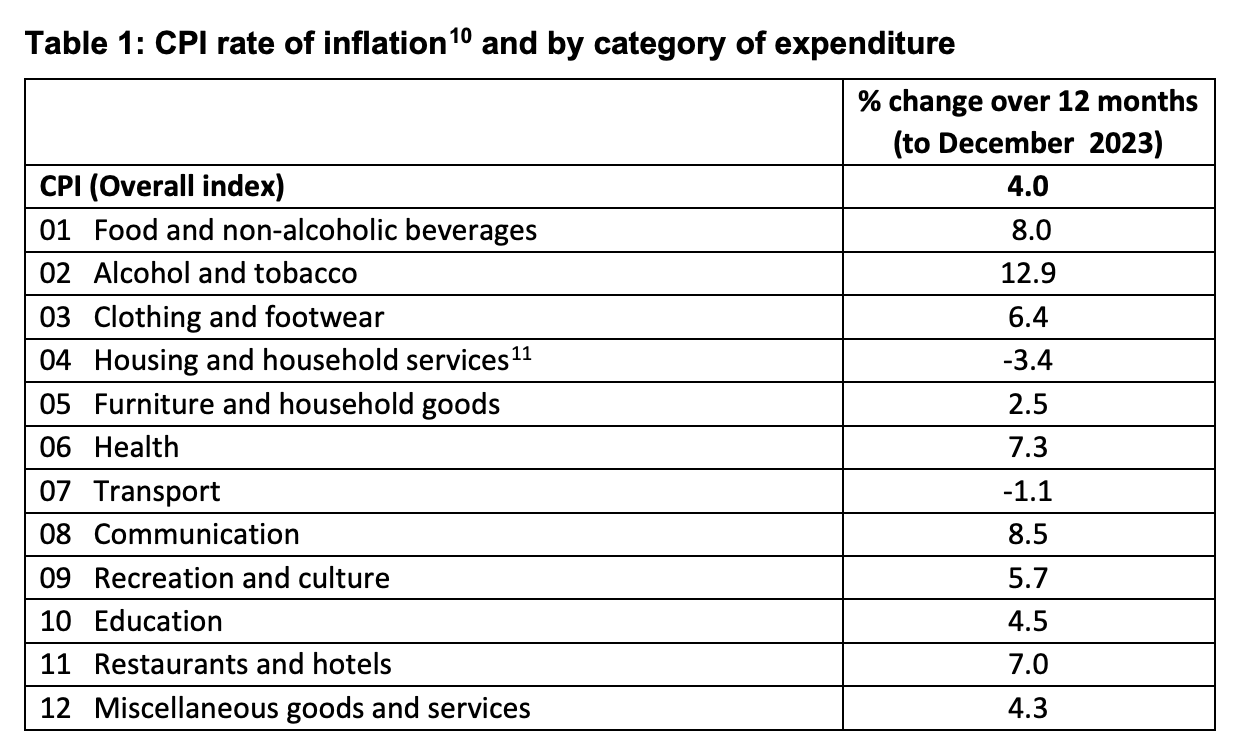

Especially interesting is the chart that shows how different parts of the classic goods basket have been rising at different rates – both because students’ average baskets will be weighted differently to the rest of the population, and because the student part of the market for each of the goods types is likely to be different too:

For example there’s plenty of evidence that students’ housing costs have been rapidly rising, not falling. And on food we know that the cheaper you shop in general, the higher inflation is for you on food – because it’s harder to trade down.

The rest is then inevitable.

Female borrowers form a larger proportion of loan borrowers and grant recipients across all products and so will be negatively impacted by a 2.5% increase in loans for living costs, mature students will be negatively impacted because a higher proportion of older loan borrowers reflects a higher proportion of part-time and postgraduate students, low-income groups will be obviously adversely affected, and students from minority ethnic backgrounds will be negatively impacted as they are over-represented across students in higher education.

It’s worth remembering that under the Equality Act 2010, the Department for Education, as a public authority, is legally obliged to give due regard to equality issues when making policy decisions – the public sector equality duty, also called the general equality duty.

So what DfE is really saying is that having given due regard to the negative impacts on students in general and the more negative impacts on students with protected characteristics specifically, it has decided to go ahead and screw them over anyway. How revealing.