Social mobility is in the mix

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

There’s a proper fascinating new study out from the Nuffield Foundation which involves the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) in the UK (previously known as the Nudge Unit), as well as Meta and researchers from Stanford University in the US.

It uses anonymized Facebook data from 20 million UK adults – and shows that low-income children growing up in areas with more cross-class friendships earn, on average, £5,100 more per year in adulthood.

So-called “economically connected communities” – where kids mix in schools, universities, and amateur clubs – predict future earnings better than almost anything except household income itself.

Proximity isn’t the whole story – two towns with similar wealth profiles (for example Kingston upon Thames and Canterbury) can diverge significantly in cross-class ties. To test the numbers, researchers even ran a version of the old Pepsi challenge – blind field tests – sending people into neighborhoods without revealing their connectedness scores. The socially fragmented places felt colder and more siloed, and the better-connected ones friendlier and more fluid.

Better than the rest

The good news for the higher education sector is that the study finds that no other institution (including workplaces, religious institutions, recreational organisations, secondary schools and the military) provides comparable exposure to high-socioeconomic status (SES) individuals for both low- and high-SES students than universities.

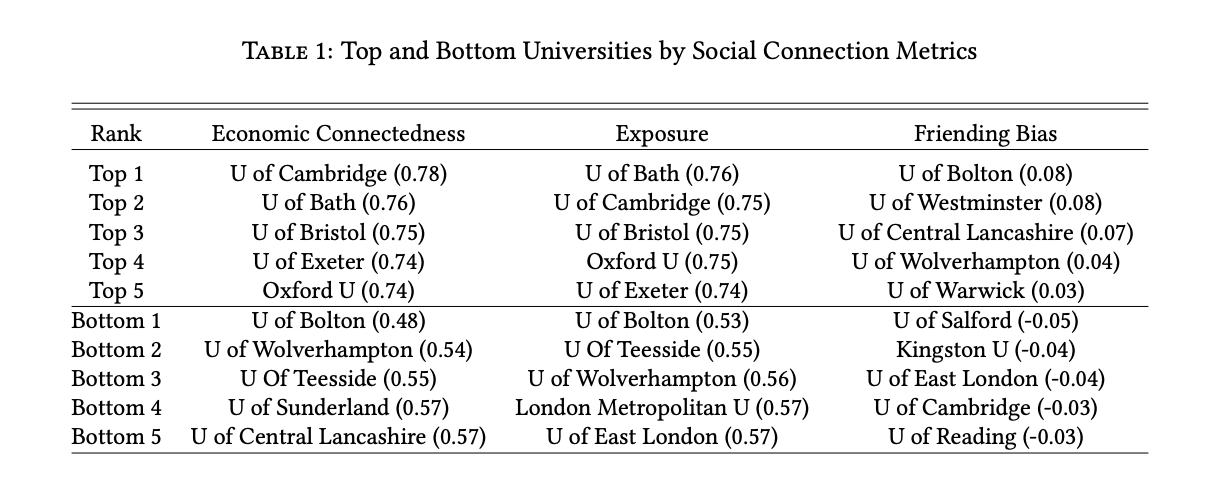

But that exposure varies hugely across universities. Economic connectedness (EC), exposure to high-SES individuals, and friending bias tell quite the story about institutional stratification.

It won’t surprise anyone to learn that the University of Cambridge tops the EC rankings at 0.78, suggesting its lower-SES students form substantial friendships with higher-SES peers. But naturally the exposure rate (0.75) indicates that three-quarters of potential friends come from high-SES backgrounds – and that’s a reflection of exclusivity rather than inclusive social dynamics.

Meanwhile universities like Bolton and Wolverhampton demonstrate lower EC (0.48 and 0.54 respectively). These correspond directly to their lower exposure rates, which raises a big question. How can meaningful cross-class connections form when the raw material for those relationships – socioeconomic diversity – remains so limited?

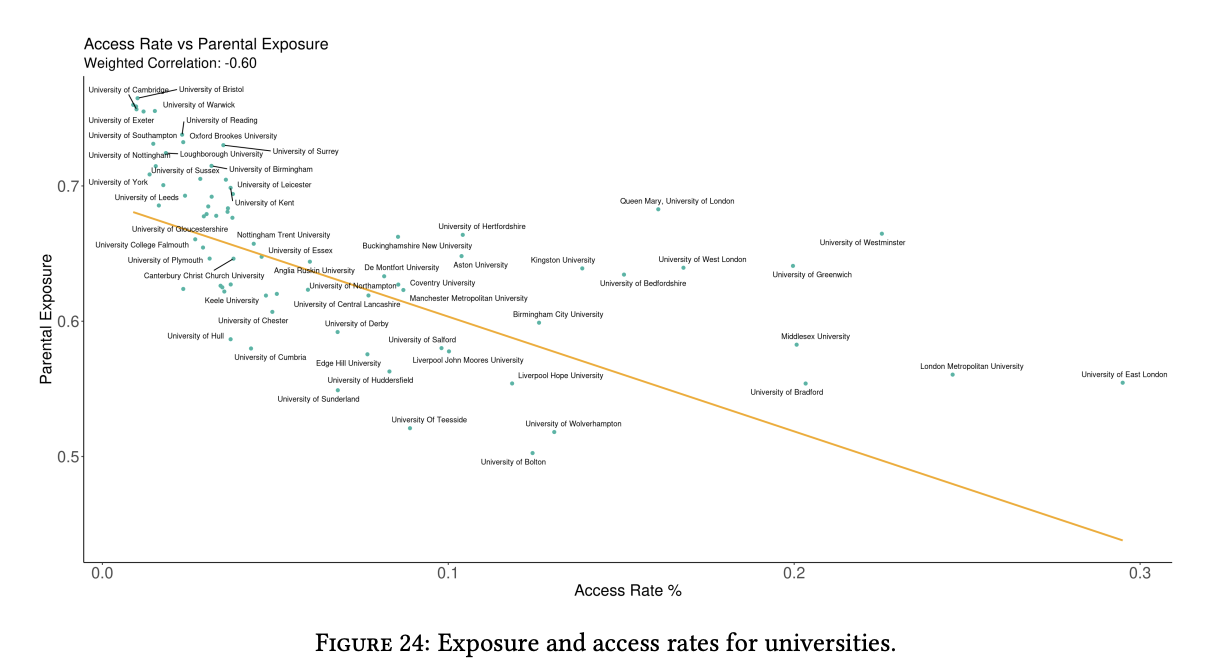

The research employs “parental exposure” as its primary measure – focusing on parents’ SES rather than students’ own economic standing, and this chart demonstrates the validity of the methodological choice:

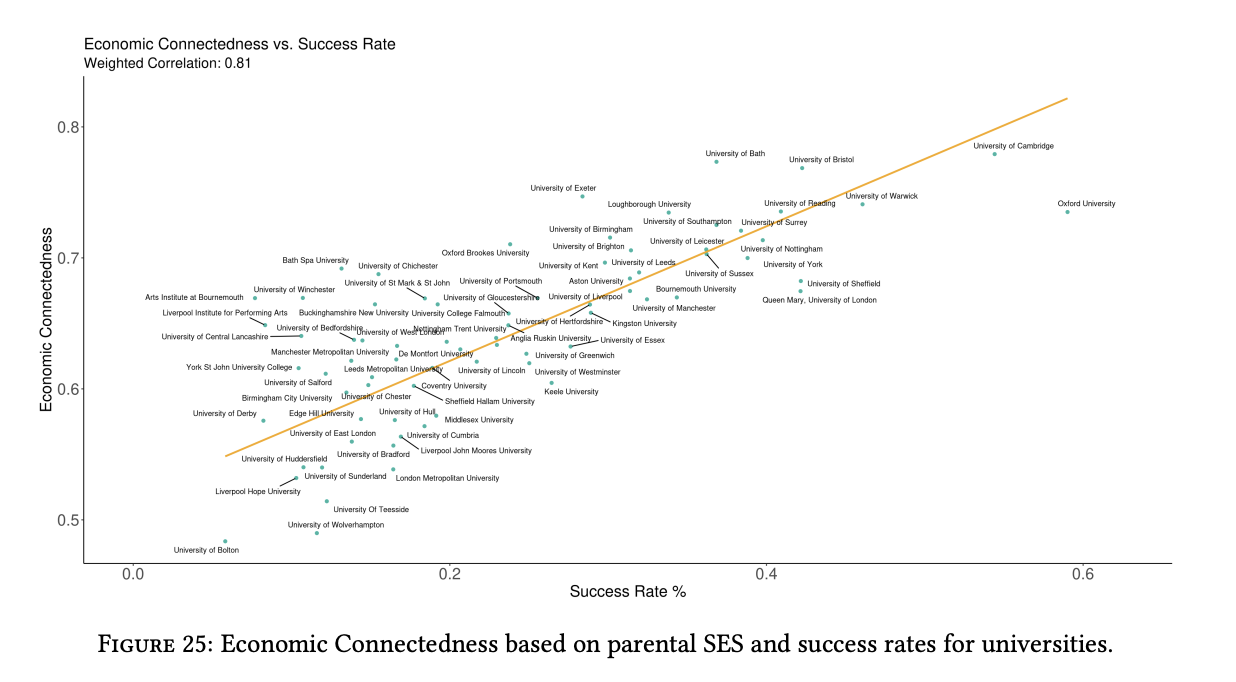

Probably the most interesting finding for me emerges in this chart – which plots economic connectedness against universities’ success rates, defined as the proportion of FSM-eligible students who reach the top quintile of earners by age 30. The correlation coefficient of 0.82 represents an astonishingly strong relationship:

Disadvantaged students who attend universities with higher rates of cross-class friendships demonstrate significantly better economic outcomes in adulthood.

Trade-offs

The problem is that the universities most effective at making valuable cross-class connections happen typically enrol fewer disadvantaged students overall. So you end up with an inevitable tension between providing opportunities for cross-class interaction (requiring diverse student intakes) and maximising access for disadvantaged students (and so decreasing exposure to high-SES peers).

Of course, to maximise access for disadvantaged students, if you have a finite number of places, you also have to find ways to turn away high-SES students whose educational outcomes prior to university tend to stubbornly track their SES. And face down the Telegraph and its allegations of social engineering.

What ought to be alarming for some universities who tend to carry the “widening participation” label is that access to HE alone is insufficient – it’s the composition of the student body and resultant social networks that significantly influence mobility outcomes. You can’t do well on graduate outcomes if the Russell Group has nicked all the rich kids.

To get anywhere on social mobility (even if you ignore the great Boomer wealth transfer) this data suggests that Wolverhampton needs to chase posh kids as much as Cambridge needs to chase the poor. And in truth, that requires structural intervention rather than the illusions (delusions) of meritocracy that plenty cling to. You’d especially look at the needless hollowing out of the 60s plate glass group caused by removal of student number controls and ask yourself if that’s basically slowly causing a division between locals studying locally and the social mobile leaving home.

That’s not to say that nothing can be done within existing structures. Student living policies that deliberately mix students from different backgrounds, work on causing commuters and away-from-homers to mix, pedagogical approaches that require collaboration across diverse teams, deliberately project-based interdisciplinary modules (because even within a university some subjects carry the WP and diversity weight) all look like they’d help. Governments can also help by reintroducing at least an ambition of restoring the school uniform principle to the way they fund the student experience and maintenance.

Oh – and that comment I’ve been inserting into the “business degrees in office blocks” franchising pieces in recent months – this research very much reaffirms my view that the poor door is problematic enough, let alone when it’s attached to a building above a betting shop 300 miles away. WP is about mixing.

On extracurriculars, the report’s broader findings are that policies that support the creation of local clubs that promote cross-class interactions for sports, arts, or volunteering can capitalise on these existing settings to cause more socioeconomic mixing.

As such my mind also drifts to the countries where student clubs and societies are operated on a city-wide basis – students in Antwerp who play chess do so together whether they’re from the University of Antwerp, the KdG University of Applied Sciences and Arts, AP Hogeschool Antwerpen or the Antwerp Management School – with SUs still operating on a provider level for representation work.

Collaboration like that between SUs in the UK has tended to focus on the money that might be saved – and that still matters now – but in all of our big cities with multiple providers, it may well be a strategic driver that can contribute to social mobility too. A Wonkhe mug is on its way to the first Registrar that asks an SU in its grant discussions to focus on social collaboration with other SUs instead of “what are you doing to help us climb the tables”.

Even more interestingly, the authors contrast tightly knit, insular networks (which can reinforce inequality) with “bridging social capital” – cross-cutting ties that link different social groups. The latter is associated with broader societal benefits like trust and cooperation:

Putnam (1995) builds on this concept and defines ‘bridging social capital’ as relationships across diverse social groups… arguing that [it] serves as a ‘sociological WD-40’ to help lubricate social interactions and facilitate cooperation across diverse groups.”

Again, both in individual providers in the tables, and within providers in subject areas and in student clubs and societies, I see much more “bonding” and much less “bridging” than we might otherwise hope for (there’s more on that in work we carried out with the UPP foundation out of the back of Covid).

Two directions

One of the lingering questions in the report – given its focus on social mobility – is, for want of a better phrase, why the rich would want to associate with the poor, or why policymakers would want to chivvy or force it against what looks like the rich’s instincts.

It’s a problem I often describe as “it’s just as important for non-disabled students to regard their lack of understanding of disability as a deficit than the other way around for social cohesion purposes” – something I was writing about a few weeks ago in relation to a fascinating social norming project from the US, and some of the things we tend to see in Europe where hobby groups are less important than subject groups.

The paper does touch on the importance of high-SES individuals forming connections with low-SES individuals in the context of social capital’s role in economic mobility and social cohesion – and notes that left to their own devices, high-SES individuals show stronger friending bias (i.e., a tendency to avoid befriending lower-SES people even when exposed to them), but that’s framed as a missed opportunity.

Economic connectedness represents the share of above-median-SES friends among below-median-SES individuals. Exposure is the share of individuals who are high-SES. Friending bias measures the tendency to form friendships with high-SES individuals relative to their presence in the university.

It doesn’t explicitly say high-SES people are worse off, but at least suggests that lowering friending bias and increasing exposure (to low-SES people) would strengthen social capital and its associated benefits although it does highlight that forming cross-class ties (from both directions) is linked to better societal outcomes, including higher levels of trust, happiness, and reduced social isolation.

Ultimately, bits of the report make clear that not everyone can climb the social ladder. The big question for policy makers – especially in a “demand” led system where choice and merit is used as a justification for extreme social stratification – is whether any effort should go into a) causing some to climb down the ladder a bit, and b) get to know, think about and even support those further down.

A really interesting report – thanks for the summary!