Philanthropic giving varies wildly across the higher education sector

Michael Salmon is News Editor at Wonkhe

Tags

The CASE-Ross Support of Education survey for higher education institutions in the UK and Ireland on first glance provides a fairly reassuring picture. Universities appear to be finding some success in bolstering their finances with increased giving from alumni and others – 2021–22 saw the funds received increase by seven per cent from the previous year, up to £1.08bn.

Total new funds committed – including legacies and pledges, which are not necessarily received in that year, but to some extent a better marker of the success of development efforts – jumped by an even healthier 31 per cent to £1.49bn.

But year-on-year comparisons don’t tell the full story – partly as response rates from the survey are dropping, with 84 institutions across the UK participating (down from 124 in 2013–14, and now only including two in Wales), and partly as the very top institutions take such an enormous share of the overall pie.

So we also see that what the report calls its “fragile cluster” – those institutions where advancement work is either nascent or struggling, depending on how generous you’re feeling – has expanded in number.

Strat your stuff

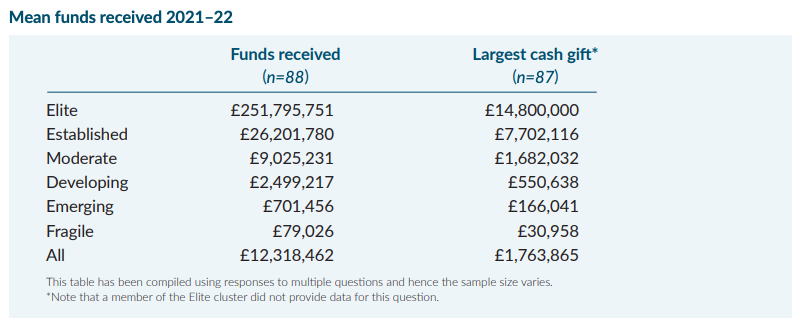

Here’s what donation income looks like, stratified across the sector:

The “elite” tier comprises two institutions – no prizes for guessing which (note also that one or the other also declined to give information for quite a few of the questions, such as donor numbers).

Partly this inequality is a question of the age of development and alumni relations teams – a majority of the so-called “fragile” institutions (n=11) founded their programmes since 2010, and for the next category up (“emerging”, n=19), a majority of programmes were created since 2005. The big players are much more established – and also have larger and better resourced teams.

The top two institutions invested more than £20m each in fundraising and alumni relations – the average (distorted by these outliers) was less than £2m. A total of 2,395 staff were employed in fundraising and alumni relations roles across the responding institutions – from the figures we get, we can estimate that around six or seven hundred of these are at Oxford and Cambridge.

Uncharitable souls occasionally question whether less prestigious and well-resourced institutions should spend time and effort targeting alumni giving as an income stream. And the report notes that staff numbers are showing evidence of a “gentle decline” outside of the elite and established clusters.

Secret benefactors?

While you might think that alumni themselves are the main givers, “non-alumni individuals” are generally just as well represented, and companies, trusts and foundations all figure highly in the total values (less than half of all mean funds are from individuals).

But of course, there’s still an enormous amount that’s not made public. We don’t, for example, get a breakdown according to nationality or even region of donors. The report limits itself to noting that “thorough due diligence about donors has become vital” – both present and historic.

The research also doesn’t touch upon where the money goes, which is a fascinating topic in its own right – partly as institutions try to find new income streams for investment in infrastructure and new buildings, which have become increasingly politicised (not that mega-donations for naming rights are any less so).

The rich enrich

But beyond capital investment, universities are also doing some very interesting things with alumni funding, from bursaries for undergraduate research to seed funds for WP international mobility (as well as mentoring and other projects that require donations of time rather than money).

The report does touch on the value of an “offer” to alumni, with overall 68 per cent of funds received from individuals coming as a result of face-to-face meetings or “tailored proposals”. It’s within these tailored proposals that alumni offices will be doing all kinds of interesting things – and it seems to be paying off in the sector as a whole, compared to the much lower proportion of funds that stem from the “mass solicitation” approach involving telethons and mailshots.

Of course, “enrichment” activities are arguably just as important to students’ development as the core curriculum, and may well go on HEAR transcripts – and are bound to go on CVs. If these are becoming less viable to be paid for by core tuition fees, this is a problem in its own right, and doubly so when the alternative funding mechanism of philanthropy is so poorly dispersed across most institutions.