OfS doesn’t seem to be able to enforce its own rules

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

The Employment Rights Bill will soon get Royal Assent – and shortly afterwards, the strike ballot minimum threshold of a turnout of 50 per cent of members will disappear.

Advance notice to employers of industrial action will change from 14 days to seven days, and many of the other procedural requirements for a lawful strike ballot will be removed.

Most of the time, students pretty much have to suck up the disruption – but over the summer it emerged that Newcastle University paid out £2.4 million to 10,934 students “for missed teaching” during strikes last year.

The delay-repay style payouts followed 44 days of strike action between March and June over proposed job cuts. Students got £100 per affected module if they were home students, and £200 if they were international students – the university proactively identified eligible students rather than making them submit claims, and had until late July to accept.

The university was fairly explicit about why. In this BBC News piece, a spokesperson says:

We are offering students compensation for missed teaching due to industrial action, which is in line with the latest directions to the sector from the Office for Students (OfS).

That direction came back in April, when OfS published a regulatory statement setting out six clear expectations for how universities should support students during industrial action.

It was unusually blunt. It noted that during the 2023 marking boycott, compensation approaches:

…were not taken consistently across the sector, leading to varying levels of support for students and perceptions of unfairness.

Only 46 per cent of affected students were offered any alternative or financial compensation. The regulator’s research found that 54 per cent of students were dissatisfied with how their university handled the situation, 41 per cent said it negatively affected their stress levels and 42 per cent said it decreased their trust in their university.

The approach taken by Newcastle – proactive compensation using money saved from unpaid salaries, clear communication and reasonable amounts – thus becomes the template for what OfS expects. But the problem is that thus far, few universities seem to be following it.

The consumer law foundation

That OfS guidance sits on a foundation of consumer protection law that has been pretty clear for years. The Competition and Markets Authority updated its consumer law advice for higher education providers in May 2023. Those changes incorporated the CMA’s unfair contract terms guidance – and specifically addressed limitation of liability clauses.

The CMA’s position is that universities cannot use “force majeure” clauses to exclude liability for things within their control. And for the CMA, universities’ own workforce relations are, by definition, within their control. The guidance also warns against terms that give providers wide discretion to vary services for “reasons outside of our control” unless the scope is tightly restricted and clearly explained.

More pointedly, the CMA has repeatedly made clear – including in case work with National Trading Standards – that industrial action by a provider’s own staff should not be listed as a force majeure event.

When OfS referred one university to Trading Standards in 2023, one of the key concerns was a clause limiting liability that included industrial action. Trading Standards considered this contrary to CMA guidance because it listed examples:

…that could reasonably be within the university’s control.

What’s going on?

I decided to take a look at as many sets of Ts and Cs for the 2025/26 year that I could find – the difficulty in finding them is almost certainly a different blog for a different day.

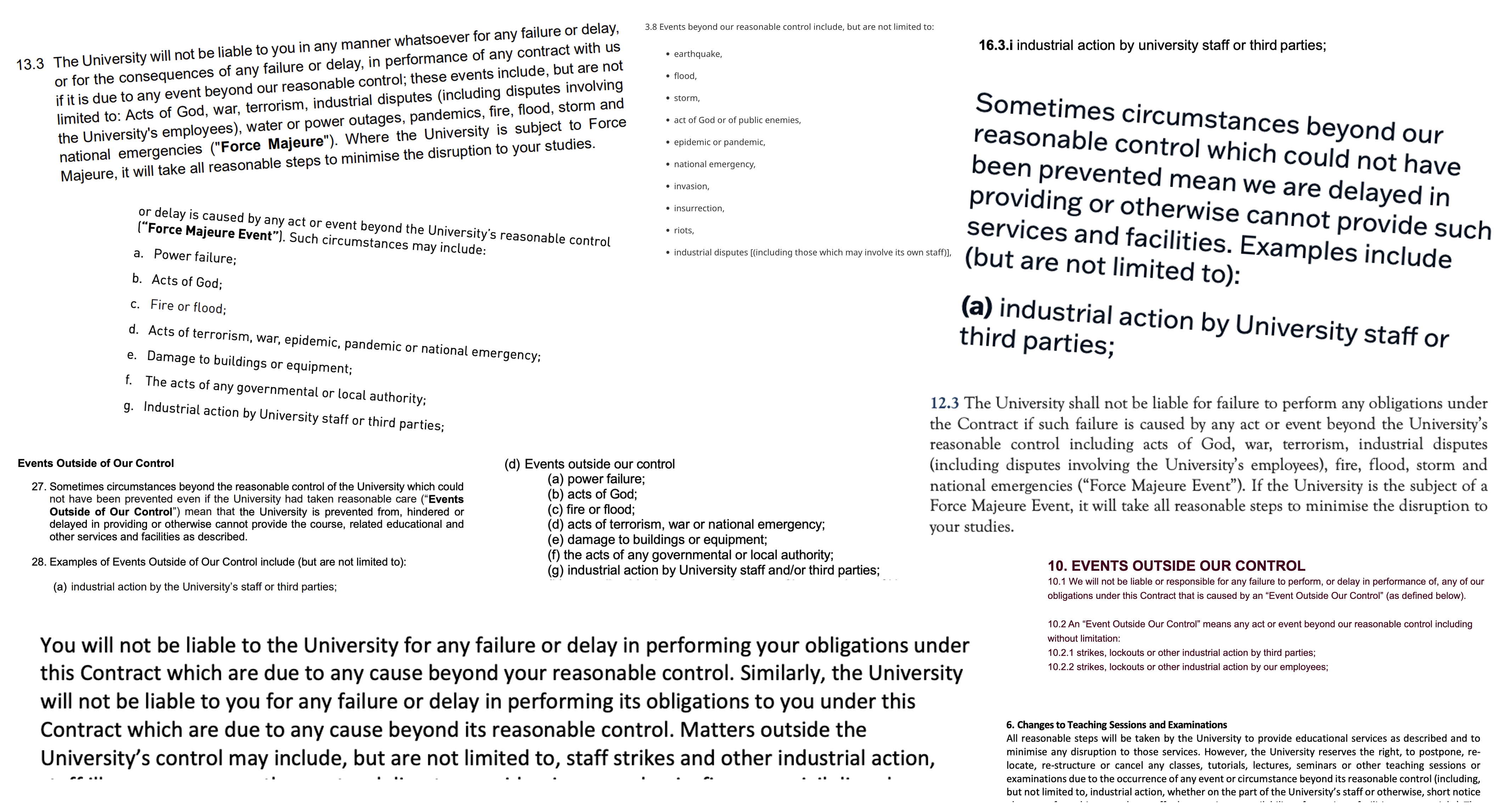

From those I’ve looked at (over 60 in England), about a third are obvious breaches – they explicitly list industrial action by their own staff as a force majeure event that limits their liability. Multiple institutions openly put disputes with their own employees inside the “events outside our control” carve-out.

Another large group – the majority – use ambiguous language. They list “industrial action” or “strikes” without specifying whose. Under CMA logic, an unqualified reference to industrial action can be read as including their own staff. These clauses are survivable with the right context and application, but they are risky. If challenged, the ambiguity would likely be interpreted against the university.

Only a small minority seem to be doing it properly. A handful of university providers explicitly state that the carve-out covers only strikes or labour disputes not involving their own staff. Some confine it to “non-university staff” or restrict it to “industrial action by third parties.” These universities have drafted their contracts in line with what the CMA expects.

The picture from Scotland and Wales is worse – maybe not a surprise when neither of the regulators seem to be interested, and the CMA thinks that this is all OfS’ problem.

Waiting for the courts

Why haven’t more universities fixed their contracts? It may be that many are waiting to see what happens with the Student Group Claim. Around 155,000 students are still seeking compensation from over 100 UK universities for disruption caused by Covid-19 and strikes between 2018 and 2022. The UCL bit of the claim has its four-week trial scheduled for between January and April 2026.

The problem is that the case may not resolve in time for the next round of strikes and/or marking boycotts – but at least in England, it’s not as if OfS hasn’t been explicit.

The very first expectation in its April 2025 regulatory statement is that universities must:

…ensure their contracts do not include terms that incorrectly limit liability to students during periods of action by their own staff.

The statement continues:

Providers should remove any such limitations in their student contracts and inform current and prospective students of these changes. Providers should not rely on these limitations as a justification for failing to deliver services during periods of industrial action.

And yet OfS doesn’t seem able to enforce its own expectations. The regulator’s previous approach has been to identify problematic clauses in individual contracts and refer them to National Trading Standards. NTS then investigates, the university works with them to amend the terms and the OfS publishes a case study presenting it as a success. Three such case studies were published, presumably to shame the sector into compliance and provide clear examples of what not to do.

But from what I’ve seen, neither the shame and signal approach nor the direct guidance is working.

Ironically, while there’s barely a whisper on OfS’ whisper on the subject of “rights” on OfS’ website, on this issue there is at least:

Where their staff are in a period of industrial action, universities and colleges should not rely on limitations in student contracts to justify not delivering services. They should remove these clauses to comply with consumer protection law. If a university or college makes any changes to its contracts with students, it should inform its current and prospective students.

Should, should and should – but they aren’t. So what next, OfS?

The OIA have set a different approach to the one outlined in this article. It is not particularly helpful that that the OIA and OfS are saying slightly different things.

The OIA sidestepped the ‘force majeure’ argument years ago and came up with a formula for compensation. Unsurprisingly, our UCU branch were emboldened by the positions taken by the OIA which encouraged further action in the form of the MAB.

As with the free speech/culture war casework this is another example of the OfS encroaching on the OIA’s turf.

The Law – by way of ‘simple’ contract law and also consumer protection legislation via the Consumer Rights Act 2015 – is totally clear: loss of teaching caused by strike action = breach of the U-S contract to educate = compensation due. And such compensation should, following the honourable example of Newcastle, by now be automatically paid out by Us. The various regulatory agencies (OfS, CMA, Trading Standards) should, of course, be energetically enforcing this; the quasi-regulatory agencies (such as the OIA, the QAA, the UUK) should be speaking up; and the consumer protection bodies like Which? should not be… Read more »

Happy to see your legal analysis is on point, Jim. I note there is a historic echo here. The CMA position on Ts&Cs re: the fee rise to £9250, while less clear, could not be easily reconciled with a detailed survey of HEIs either. No sector-wide change came about, even after a selection of undertakings with a few institutions for failure to specify inflationary fee-rises with adequate particularity. Finally, to ‘What About the OIA?’, public bodies took all kinds of stances on the fees issue too. I note that OFFA indirectly played a role in consumer law by forcing universities… Read more »

Well done for trawling for the contracts. The consumer and the contract laws are clear, but not its application to the universities, for which test cases are required. I argue as academic judgments are non-justiciable, higher education and its provision of degrees is neither a good nor a service, so the education parts of the contracts are unenforceable. CMA, OIA, and OfS are bureacratic institutions which obscure the fact with complex, hard to navigate guidance and procedures. So why bother with re-writing contracts or even publishing them?