It was hip to be square

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

The Square Tavern in Camden – just across the road from Euston Sq station – holds a lot of memories for me from my days at NUS. I seem to remember that it was the NUS Staff “pub of the year” for a few years’ running. But the memories were stronger for one group of students a few decades earlier from UCL.

The story of its location – Tolmer’s Square – surrounds a group of students who stumbled across a local conflict and, almost by accident, became central actors in shaping what followed.

Their involvement not only changed the course of a struggle, but also transformed the way they saw their education, their role in society, and the relationship between knowledge and power.

Those were the days and all that.

From theory to reality

In May 1973, five UCL undergrads set out on what was meant to be an ordinary five-week planning project.

They were pretty bored of the remoteness of their academic work – lectures and essays that seemed to float above the realities of urban life. For inspiration, their tutor tipped them off about activities across the Euston Road, where a controversy was brewing over plans to redevelop Tolmers Square.

What they found shocked them. For over a decade, Camden Council and private developers had been discussing major redevelopment schemes. But almost no one living or working in the neighbourhood knew what was happening, when it would happen, or how it would affect them

The Council had gathered no survey data, commissioned no social studies, and made no serious effort to consult local people. Residents’ first encounter with “planning” was usually a clearance order shoved through the letterbox.

For students trained in urban planning, this absence of knowledge and participation was a shocking revelation. For them, the city was being shaped not by evidence or democratic deliberation, but by deals in committee rooms and calculations of land value. It was the gulf they had been taught about in lectures, but for real – the distance between professional expertise and the lives of those subject to it.

They also uncovered a secret(ish) deal. In the late 50s, when the London County Council needed part of Joe Levy’s corner site for road-widening, rather than pay him compensation it quietly agreed that he could redevelop a much larger thirteen-acre block – the future Euston Centre – at very high density.

Armed with that hidden advantage, Levy was able to buy up surrounding plots cheaply, before partnering with Wimpey to produce half a million square feet of glass and steel offices, shops and luxury flats.

The development only cost £6 million but was valued at around £80 million on completion, a windfall that underlined the extent to which public authorities had colluded in handing vast profits to private speculators.

Backroom bargains

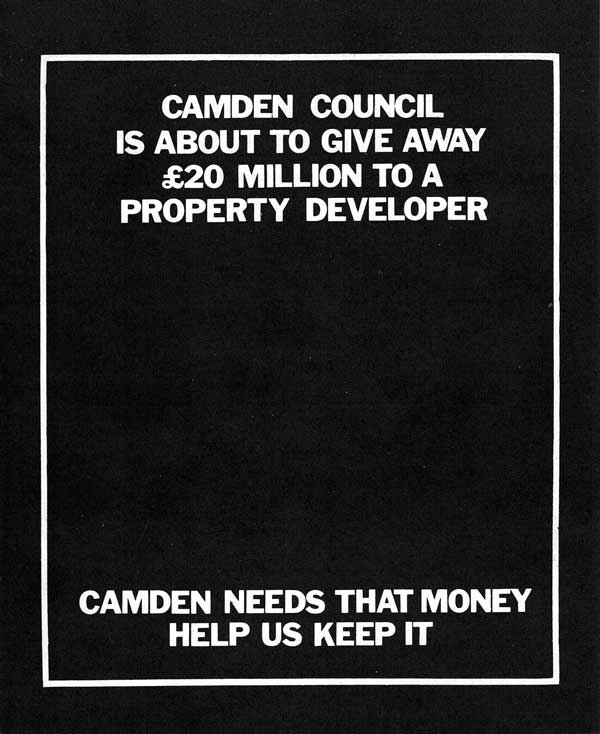

For the student campaigners at Tolmers, the “Levy Deal” became a byword for the kind of backroom bargains that displaced communities and prioritised property over people.

They responded not by retreating to the library but by knocking on doors. They surveyed who lived in the area, what they thought of redevelopment, and what would happen if current plans went ahead.

Their report was damning. It accused decision-makers of failing to understand the “exciting variety” of Tolmers, and of seeking to replace it with a “drab uniformity.

Instead of comprehensive demolition, they proposed gradual, piecemeal development – repairing and retaining as many buildings as possible and allowing new ones only when the old reached the end of their natural life. For them, doing so would allow people to remain in the community, and avoid the trauma of mass displacement.

These ideas were not unique. By the early 1970s, critiques of wholesale redevelopment were circulating widely in universities and the media – but their contribution was to make those arguments concrete.

They supplied data, lent academic credibility, and – crucially – shared their findings with local people who could act on them. At their final project presentation, they invited residents to hear their conclusions.

The shock of what they heard prompted those residents to form an ad hoc committee – and out of that, the Tolmers Village Association (TVA) was born

As they often are throughout history, students were catalysts. They didn’t stay to lead, but their research and activism provided the evidence and the urgency for locals to organise.

From project to participation

Their role didn’t end with the hand-in of a project report. Some of the same students, joined by others, threw themselves into the life of the fledgling TVA. They helped launch Tolmers News, a community newspaper designed to inform residents of the latest developments and give them a voice

Twenty issues appeared over 18 months, edited in rotation, reflecting both the energy and the chaos of the sort of grassroots journalism that was often evident in the numerous student newspapers of the time.

They also supported petitions and campaigns. One early success came when rumours spread that the site of the derelict Tolmer Cinema would be turned into a car park. Students joined residents in gathering 300 signatures demanding it instead be used for children’s play and open space. The application was refused – maybe it would have been anyway, but the victory bonded neighbours, students, and shopkeepers alike.

The activity blurred the boundary between study and struggle. It had begun as a bt of coursework, but morphed into a form of community engagement that was both educational and political. Students discovered that planning was not merely about maps and models, but about alliances, tactics, and power.

Their arrival was not universally welcomed. Long-standing working-class tenants were often sceptical, seeing little point in delay when what they wanted most was rehousing with basic amenities. For them, the TVA’s lofty aims about preserving “village atmosphere” or fighting the Levy Deal seemed remote.

At the same time, some business owners worried that student activists were meddling do-gooders, more interested in ideological battles than practical improvements. Developers, meanwhile, dismissed them as idealists playing politics.

But relationships were forged. Students worked alongside Asian shopkeepers, young tenants and middle-class residents that had moved into the area. Working together, they produced newsletters, staged exhibitions, and organised carnivals.

They also formed bonds with squatters who started occupying empty properties in Tolmers from 1974. Many of the squatters were themselves students or recent graduates, politicised by the era’s radical currents. They brought energy, creativity, and sometimes confrontation to the movement. Direct action – bonfires on derelict land, occupations of vacant offices, impromptu gardens – sat alongside more formal lobbying of Camden Council.

Civic impact

For the students, Tolmers was transformative. What had started as a search for “reality” became an education in democracy, class, and community. They saw for real how planning decisions, dressed up in technical language, could conceal battles over land, profit, and survival.

They learned that research could be a weapon rather than just an academic exercise. And they experienced the frustrations of trying to build coalitions among groups with pretty divergent interests.

Some carried the lessons into their careers. One later reflected that Tolmers taught them “more about planning than any textbook ever could”. Another noted the sheer exhilaration of seeing their work matter – the idea that data gathered in dingy tenements could alter the course of policy.

But there was also disillusion. They saw how quickly councils and developers dismissed community knowledge, how fragile local organisations could be, and how idealism collided with the day-to-day needs of residents desperate for a decent home. For some, it was a hard but vital lesson about the limits of participation and the resilience of power.

Tolmers eventually became a patchwork of outcomes. Some housing was preserved, some rebuilt. Parts of the community survived, others dispersed. And the pub’s still there – now a haunt for the various rail workers’ unions that have offices nearby.

Students’ role may have been temporary, but it was pivotal. Without their survey and their report, it is doubtful that the TVA would have emerged in the same way. Without their energy, communication tools like Tolmers News might never have existed. And without their willingness to link theory to practice, Tolmers might have remained just another victim of speculative redevelopment.

Their story is also one about universities and their surroundings. Here, students didn’t remain hidden in lecture halls but crossed the road to stand with those whose lives were on the line. They challenged both their own institution’s detachment and the council’s indifference. In doing so, they redefined what it meant to be a student – not just a consumer of knowledge, but a citizen of the city.

Though they eventually moved on – back to their studies, into professions, or onto other causes – the impacts of their involvement lingered. In Tolmers they learned – and taught others – that cities aren’t just bricks and mortar, but battlegrounds of belonging, and that even students can make a difference when they cross the line from observation to participation.

There’s more on the Battle for Tolmers Square in this book from 1976, this blog from 2018 and a number of stories from students and others on the Tolmers Village Forum, which is where the photos above are from.

There must be a number of examples from around the country of student activists being a catalyst in situations like this. In Sheffield, for example, students were instrumental in halting ‘slum clearance’ programmes which would have seen solid and serviceable terraced housing demolished for the want of installing indoor bathrooms. As well as campaigning, they helped residents apply for grants to improve their homes so they could no longer be condemned as uninhabitable.

see: walkleyhistory.wordpress.com/walkley-action-group/

These localised campaigns are recorded by individual universities and local groups, but has anyone brought them together?