Improvements to maintenance support are nothing of the sort

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

It’s difficult to count the maintenance grant announcement that was trailed at Labour Conference. That’s to be introduced by the end of the Parliament, at an unspecified rate, to be given to an unspecified group of students, on an unspecified group of courses.

Uprating the core living costs maintenance loan by forecast inflation (the Office for Budget Responsibility’s projection for RPI-X in the first quarter of the second of the two calendar years that a given academic year spans) is, of course, the system that has been in place since George Osbourne scrapped maintenance loans.

It’s a system, lest we forget, that has delivered a collapse in on-campus engagement, has entrenched food banks on campus and has seen the percentage of students engaged in part-time work during term double from a third to over two-thirds.

And the problem? It’s going to get much, much worse – as the deep and growing inequalities already present in the system get baked in for a full Parliament.

Brace brace

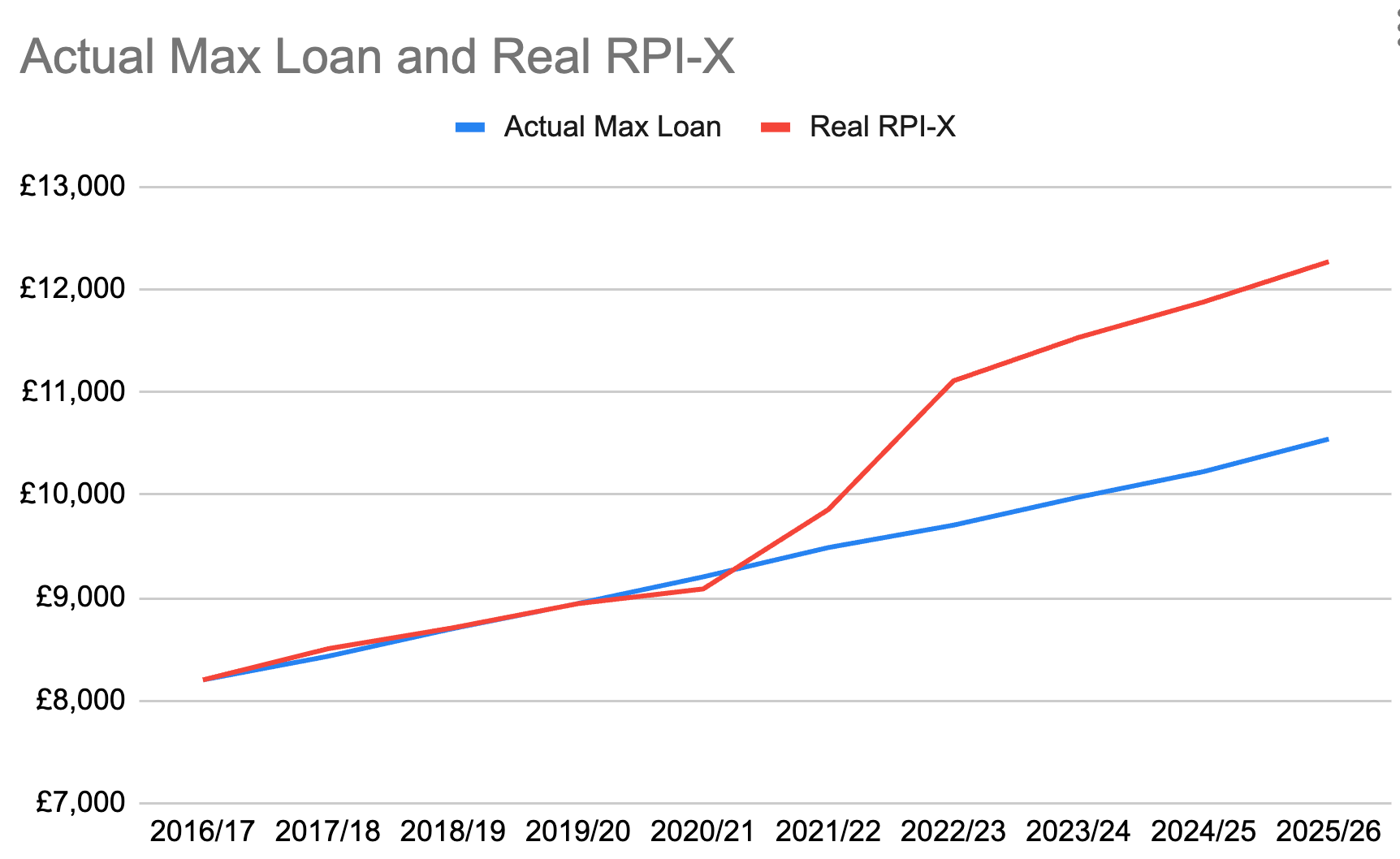

The first problem is in the use of a projection rather than actual rate of inflation. The OBR’s projection has been consistently wrong in recent years – such that if 2016/17’s baseline of £8,200 a year (away from home, outside London) had been uprated by actual inflation in the magic quarter, it would now be £12,186, rather than the £10,544 on offer in 2025/26.

DfE could correct the errors, or just use a live measure of inflation. But it doesn’t – and so the impact compounds over time.

The second problem is in the means test. This year maintenance loans increased by the OBR 26Q1 projection of 3.1 per cent (RPI was 4.6 per cent in August), but the Department for Education (DfE)’s own projections are that the mean average loan will only rise by 2.6 per cent this year.

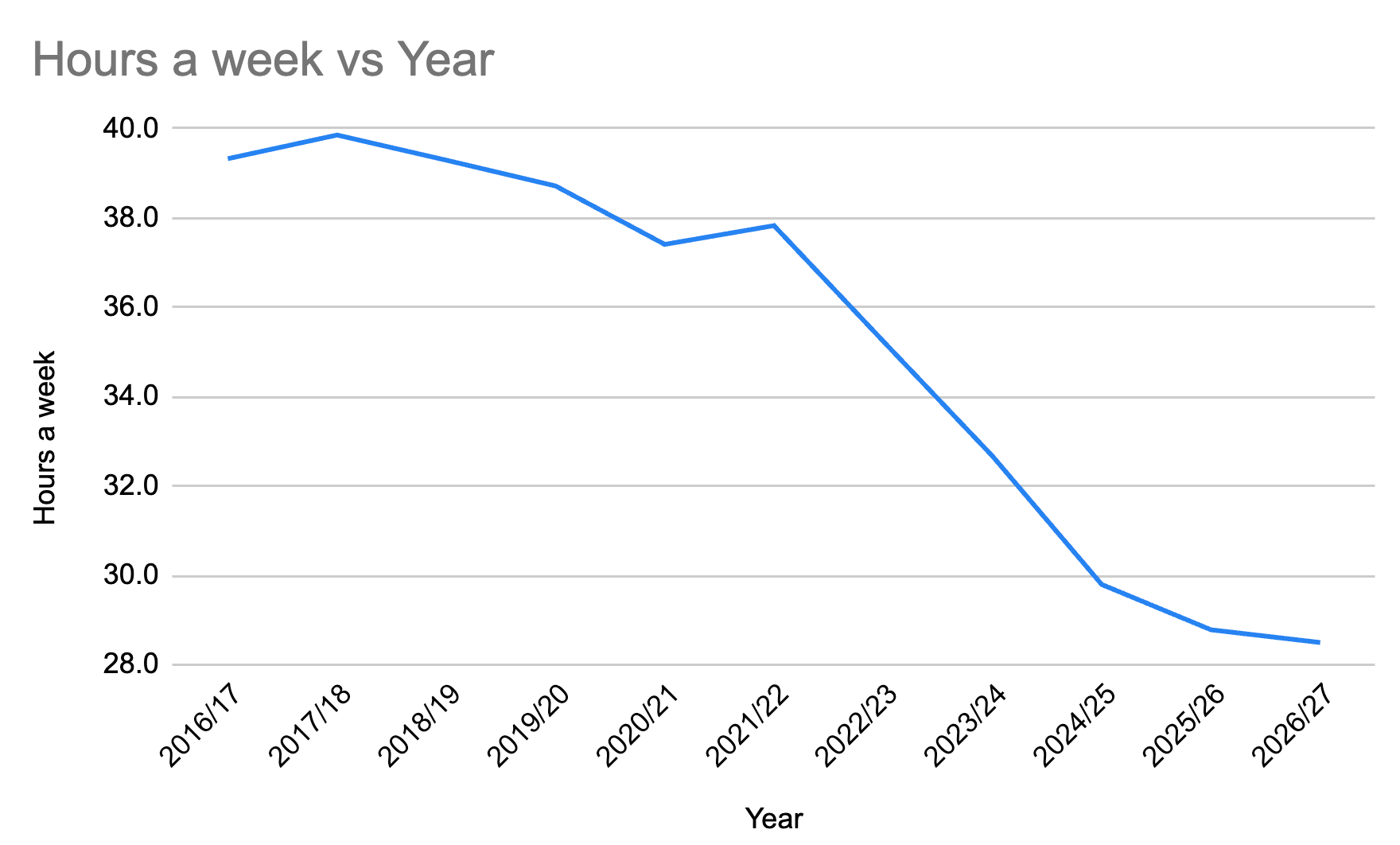

That’s almost certainly because the £25,000 threshold hasn’t changed since it was announced in 2007 – a threshold that now means not even a single parent family working 40 hours a week on the national minimum wage will get the maximum loan.

For a family that was earning £25,000 in 2007, the maintenance loan is now worth £3,986 less in real terms than it was a decade ago. For a family earning £25,000 today, the shortfall caused by the above two factors is £3,149. Even for a family whose household income has been less than £25,000 for the whole of the last 20 years, the maximum loan is worth £1,642 than it was a decade ago.

The third problem is that the baseline was never anchored in students’ actual costs. Even if you dismiss the HEPI/TechnologyOne Minimum Income Standard for students as a fantasy, every major review of student finance in recent years in the nations has pegged student maintenance to the minimum wage.

Indeed, the Augar review – much of which is being rolled out in the Post-16 Education and Skills White Paper – called for the maximum loan to be set at minimum wage x 30 weeks x 37.5 hours, to represent the time students spend studying instead of working.

If Augar’s proposals had been realised, the max loan for 2026/27 would be £14,299 instead of what’s likely to be £10,871. In reality, Augar miscalculated – the credit system represents 1200 hours, not 1125. That would mean next year’s maximum should be £1,525.

It’s all the more galling because increases in the minimum wage are now calibrated to reflect actual increases in living costs. At Labour Conference, Bridget Phillipson said:

[students’] time at college or university should be spent learning or training. Not working every hour God sends.

The problem is that next year her maximum maintenance loan will cover the equivalent of 28 hours a week – leaving students attempting to top up via part-time jobs, all while the two industries that have seen the heaviest job losses – retail and hospitality – are the ones most amenable to combining with study.

And the rest

Those are just the headline problems. Average inflation belies problems like this winter’s rocketing costs of food – students spend more of their money on food, so student inflation is likely to be higher.

Augar called for a review of London weighting, the costs facing students with children, and commuter students – recommendations still never responded to.

The interaction with the benefits system remains broken, the LLE generates a range of bizarre incentives, and Augar’s recommendations on the price of student housing remain ignored too – replaced in the White Paper with a vague “statement of expectations” on supply which fails even to reflect the widespread debate in Parliament about the potential impacts of the Renter’s Rights Act.

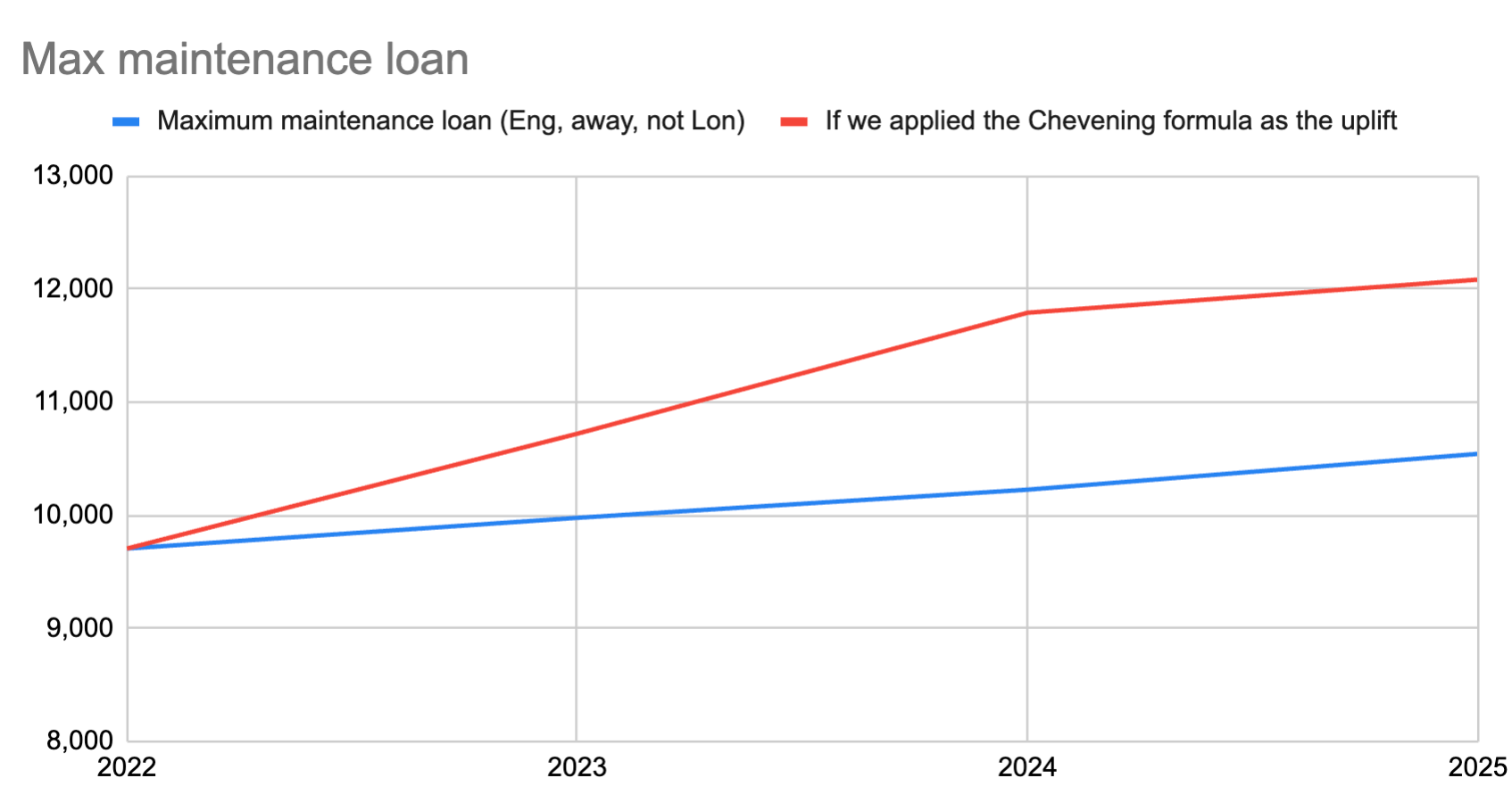

The impacts of all of this spread, too. The maintenance requirement for international students is set at the maximum maintenance loan level for English students – sending a signal that study here can be afforded on £10,544 a year when it clearly can’t. That’s not a signal the Foreign Office believes – instead, for Chevening Scholars, it applies a student set of basket weightings and uses the previous April’s real CPI.

Even if we just took the 2022 as a baseline and applied the Chevening formula, the max England non-London away from home maintenance loan would now look like this:

It’s HMT that manages the subsidy on student loans for the devolved nations, on an equivalent basis per head of population. Massaging down the money loaned to students in England means less subsidy elsewhere – putting already broken respective promises on anchoring to the minimum wage further from reach in both Wales and Scotland.

The likelihood of students turning to commercial debt rises, and the increases in tuition fees coupled with the now 40 year term of the loan all also mean that average graduates will be paying significantly more for their HE than they were ten years ago – despite having a demonstrably worse experience.

In her speech to Parliament, Bridget Phillipson said to any young person growing up in England today that if they want to go to university, if it is right for them, and if they meet the requirements, “the government will back them”. God alone knows what turning on them would look like.