How much are we expecting parents to put in in the coming year?

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

This coming year that loan will be £9,706 (£9,179 in a student’s final year) – which as we’ve noted here before, is only a 2.3 percent increase on last year because of how old the projections are that the Department for Education (DfE) uses for inflation.

The basis for the figure has been lost in time – illustrated by the fact that those in London only get an uplift of 31 percent on that core (a basic standard of living in London is up to 58 percent more expensive than in other urban areas of the UK) and that those living at home get 84 percent of the core loan (harking back to time when rent was a much smaller proportion of a student’s costs).

As we’ve also noted on here before, though, not everyone gets that maximum. Unlike in Wales where students are all assumed to be adults, in the other three nations we ask parents to chip in towards the max. Martin “Money Saving Expert” Lewis has long been campaigning for that “hidden” parental contribution to be made clear – and even that ignores that even if the maximum can be reached, it’s barely enough to survive on.

The big problem with that parental contribution has long been that the thresholds used to calculate it have been frozen in time since 2007 – despite the fact that earnings have been rising over the past 15 years.

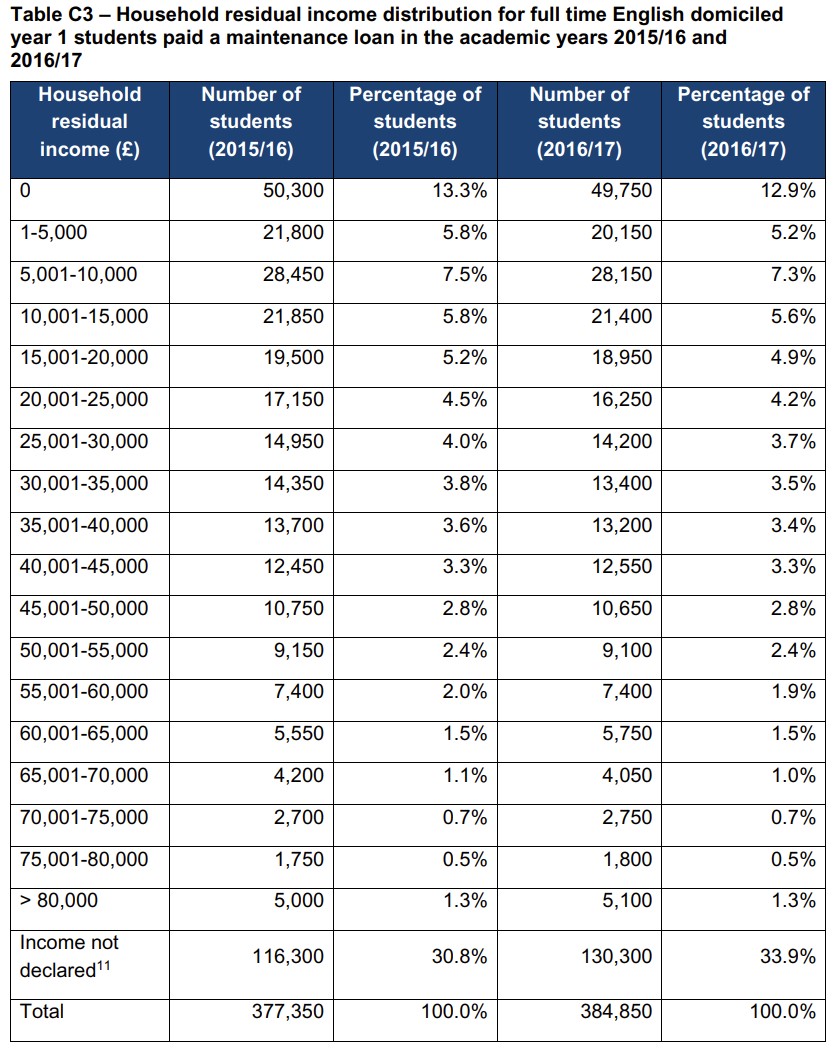

We don’t have more up to date figures than this, but bear in mind that 27.2 percent of students in the England loan system had a residual household income of £25,000 or less in 2016/17, down from 28.8 percent the year before.

That’s right – despite the fact that the government keeps saying that more disadvantaged students are in higher education, the freeze on that threshold means the goalposts keep moving on what we count as a low income family for maintenance purposes – that £25k would now be about £33k if we’d have been updating for earnings.

That’s explains how John Denham estimated that a third of English domiciled students would get the maximum maintenance package back in 2007, but despite more and more lower income students making it in, the percentage of students getting the full amount continue to fall.

But we now have another problem, don’t we. Not only has that threshold not been rising for earnings, we’re now in a situation where the amount of free cash available to a household to contribute to the costs of another household is under major pressure, illustrated neatly by this little exchange on Twitter a couple of days ago:

No – those parents don’t expect their headline income to drop. But they very much do expect the proportion of it that they expect to be able to spend on another household to drop. And there’s no help for that.

In that chart above, 54 percent of families were earning £45k or less – the sort of salary that Chancellor Nadhim Zahawi says will find the rise in their own bills “really hard”, let alone someone else’s.

This all in theory means that as well as properly uprating the core for inflation, we ought to recalculate and deduct from the family earnings assessment families’ energy usage over a threshold. Because it was neither expected, nor counts as optional or discretionary.

It might be complicated and there may be blunter ways of doing it, and obviously Wales’ system (which just allows everyone to borrow the full loan) would be better. But it’s important that we try to get across the point – that the way we calculate household income as a measure of available cash to spend on kids’ education is, right now, utterly broken.

As the person from Student Finance England makes clear above, there is a mechanism that allows students to get their loan adjusted if their income has dropped. That should be adapted for these purposes, I think – and universities with earnings threshold-based bursary schemes should do this too of course.

Of – and of course those in Scotland and Northern Ireland should lobby both for more bursary/loan (the headline figures are lower in both countries) and for the thresholds there to be addressed in a similar way to the way I’ve described above.

(All that family income does in Wales is adjust the proportion of the headline that is issued in grant v loan. That is arguably not a priority to worry about right now.)

Do bear in mind that stealth terms changes introduced by the government this year mean that it will be writing much less off from every maintenance loan issued than it was previously – its subsidy into that loan scheme is going down. Is it too much to ask that some of the saving to the Treasury is given back to DfE to allow students to be a little less hungry and cold?