For students, inflation hits different

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

The BMA argues that their pay has been eroded significantly in real terms since 2008 – basing their claim on the Retail Prices Index (RPI).

That shows a 21 per cent drop in earnings in real terms since 2008 – hence their demand for a 29 per cent pay rise to achieve “full pay restoration”.

The problem is that in 2013, RPI was stripped of its status as a “National Statistic” following an assessment by the UK Statistics Authority, primarily due to inherent flaws in its methodology – not least its use of the outdated “Carli formula” which tends to overstate inflation by about 0.7 percentage points compared with CPI/CPIH.

So when the Nuffield Trust uses alternative inflation measures like the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) or CPIH (which adds in housing costs), it shows a smaller real-terms pay decline – between 4 per cent and 10 per cent since around 2010-11.

Notwithstanding that neither measure is likely to capture the particular spending basket of Junior doctors, the disagreement therefore centres both on which inflation metric is the right one, and which baseline year to use for comparison.

I’d love to suggest there even is an argument going on about inflation in the student maintenance loan system (other than on this website), but let’s imagine for a minute that there is.

Students never had it so good

In England, in theory, maintenance loan rates have been rising by RPI for a decade now – a headline that might suggest that students have never had it so good.

Meanwhile in Wales and Scotland, the policy intent has been to move to the National Minimum Wage as the basis for calculating increases – also good news given that the Low Pay Commission has recently been charged with ensuring that the NMW tracks actual cost of living (the sort of thing that the Living Wage Foundation has been doing for years).

But some devils in the detail dampen the excitement:

- The Department for Education (DfE) has been using Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) projections of inflation rather than inflation itself

- (Specifically, RPIX for the second quarter of the academic year – RPIX excludes the mortgage interest payments component from RPI)

- Those projections were significantly undercooked by the OBR during the inflation crisis, and it has also refused to correct for the errors over time

- The headline rates in England (and Scotland and Northern Ireland) are means-tested for family earnings – and despite gently rising earnings, the thresholds in all three countries have been frozen in time for for years now

- Wales and Scotland both theoretically pledged to move to NMW as the basis for increases – but both seem to have abandoned doing so as costs have increased

- Devolved loan schemes are managed by the Treasury, and are not allowed to become more expensive than England’s without specific local top-up. The precise way in which that is judged remains a mystery – but that is likely to have contributed to the abandonment of NMW as the uprating measure

- In England and Northern Ireland, we reduce the amount of loan for living at home, and increase it for living in London – by proportions unchanged in decades

There are plenty of articles on the site about the various impacts of all of that – but overall I, like the BMA, have tended to use RPI rather than CPI to demonstrate the financial situation that students now find themselves in.

As such, it does look like the undershooting problem is about to hit again – both the maximum maintenance loan and the maximum tuition fee (along with PG loan rates) were based on the October 2024 RPIX projection for Q1 2026 of 3.1 per cent.

As of June 2025, RPIX is running the significantly higher 4.3 per cent.

(Wales somehow got away with using the OBR’s March 2024 projection – which was just 1.6 per cent – while simultaneously using the OBR’s October 2024 guess for fees!)

Blame it on the baseline

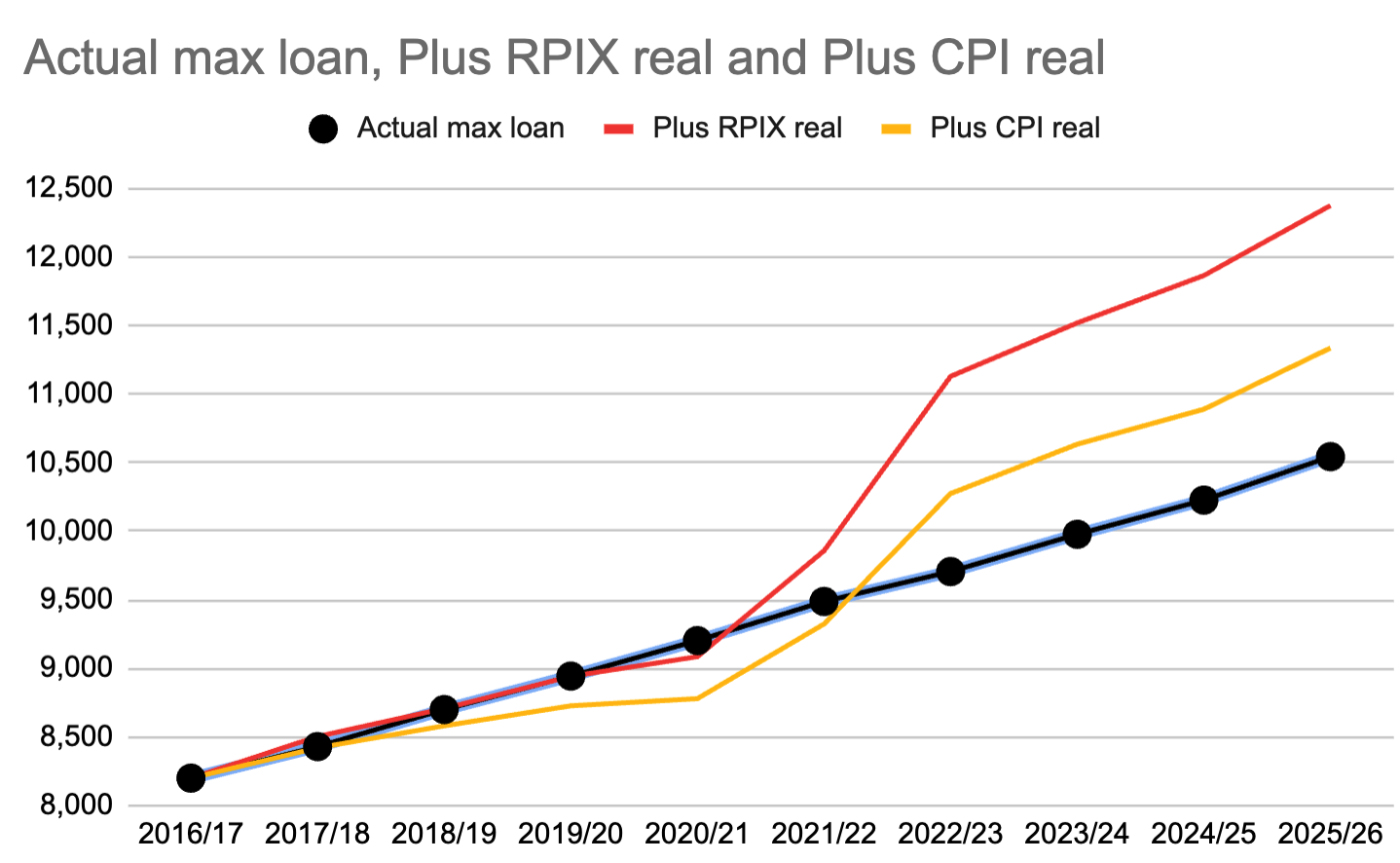

If we use the year that then Chancellor George Osbourne abolished the student grant (replaced by more generous maintenance loans) as the baseline year, the comparison on the max loan (away from home, outside of London) for England looks something like this:

In the years to 2021/22, if you ignore that frozen means test, increases outperformed CPI – but since then it’s been looking pretty bleak either way (for “real” for 2025/26, I’ve used the latest month’s figures).

But what none of that does is look properly at the basket of goods. Not only is it likely that a Junior Doctor’s basket of goods differs from that of the general public, a student’s basket of goods is likely to differ significantly too.

As I type, it’s just been announced that data from the British Retail Consortium and NielsenIQ shows a continued surge in food price inflation – up at 4 per cent compared with the same period last year, from 3.7 per cent growth in June and above a three-month average of 3.5 per cent.

It would therefore be helpful to have some sort of measure of student inflation. From time to time, firms do have a go – but increasingly what we see is calculations based on what students are actually spending rather than the cost of goods and services they (or should be) buying – so those calculations are better at showing us how students are cutting back than they are at showing us how prices are rising.

If we therefore turn to the student Minimum Income Standard (MIS) approach (developed by the Centre for Research in Social Policy (CRSP) at Loughborough University for HEPI/TechnologyOne), we find that in an ideal minimum student basket, Food & non-alcoholic beverages is roughly three times as dominant for students.

ONS has annual inflation for Food and non-alcoholic beverages to June 2025 at 4.5 per cent. Health is up at 4.4 per cent, Communication costs are running at 4.9 per cent, Recreation and culture is at 3.3 per cent, and alcohol is up at 6.4 per cent.

Meanwhile the much less important to students Furniture and household goods is down at 0.9 per cent, and Restaurants and hotels are running at 2.6 per cent. And we’d be daft to even look at the housing costs in the official figures, given that the characteristics of the sub-market mean student rents always seem to rise faster than those for everyone else.

There is a very real risk now of student poverty – students making impossible choices having, to some extent, been misled into believing that their participation would be affordable.

It places an extra responsibility on universities to offer advice that is about realistic budgeting rather than cheery picking figures that make a given provider’s city look affordable. Even with the bursaries on offer in APPs, many universities really ought to be telling many students not to enrol.

But nationally, in England (and Wales), we’ve only had two proper looks at Student Income and Expenditure in recent decades – one in 2014-15, and a (thanks to the pandemic, fairly faulty) one in 2011-2012.

We very much need another.

Why just focus on maintenance costs? Given that until recently tuition fees were frozen, CPI overstates the inflation experienced by students and RPI even more so.

Because students (home students) don’t “face” tuition fee costs – graduates do.