For a 35k family, degrees cost more in Scotland

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

It wasn’t him – it first appeared in a 1981 Narcotics Anonymous pamphlet, warning addicts that expecting to quit on their own while continuing to use was daft. Einstein wouldn’t have been so offensive.

I mention this because the Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) has published its report on the funding of tertiary education in Scotland, and the quote sprung to mind.

Back in May the RSE convened a two-day conference, led by Sir Andrew Cubie (of the 1999 Cubie Commission that recommended the graduate endowment scheme) and Alice Brown (former chair of the Scottish Funding Council).

The resulting 40-page document synthesises presentations from various experts, includes a commissioned piece from college principals Audrey Cumberford and Paul Little, and concludes with an afterword from Baroness Wolf.

The stated aim is to provide an “evidence base” for whoever forms the next Scottish Government after May 2026. The report explicitly declines to make recommendations as an RSE position, instead offering eight “guiding principles” – fairness, sustainability, access, parity of esteem, coherence, clarity, flexibility, balance – that are not very subtly designed to nudge a new government towards abolishing free fees.

In media interviews around the launch, Cubie has been more direct than the report itself allows. He told The Times the “platform is burning” and suggested the graduate endowment model deserves reconsideration – citing polling showing 80 per cent acceptance when his original scheme was introduced. Carnegie Trust polling found 48 per cent favoured fees based on ability to pay, with 29 per cent opposed.

The Scottish Government’s response has been as consistent as ever – free tuition is non-negotiable. Rocks will melt, and all that.

Every few months we get a report like this. Each one says that funding is unsustainable, that colleges are being neglected, that universities are on their knees and that the model needs reform. Each one lands, generates a day or two of coverage, and disappears into the same drawer as its predecessors.

Kate Ogden from the Institute for Fiscal Studies was on one of the conference panels, and the discussion summary hints at some of the real questions – whether lower funding in Scotland represents “higher operational efficiency” or “underfunding,” and how block grant adjustments for Scottish policy choices on benefits have squeezed other budgets.

That question of what’s being left on the table is the big one for me.

Subsidy on the table

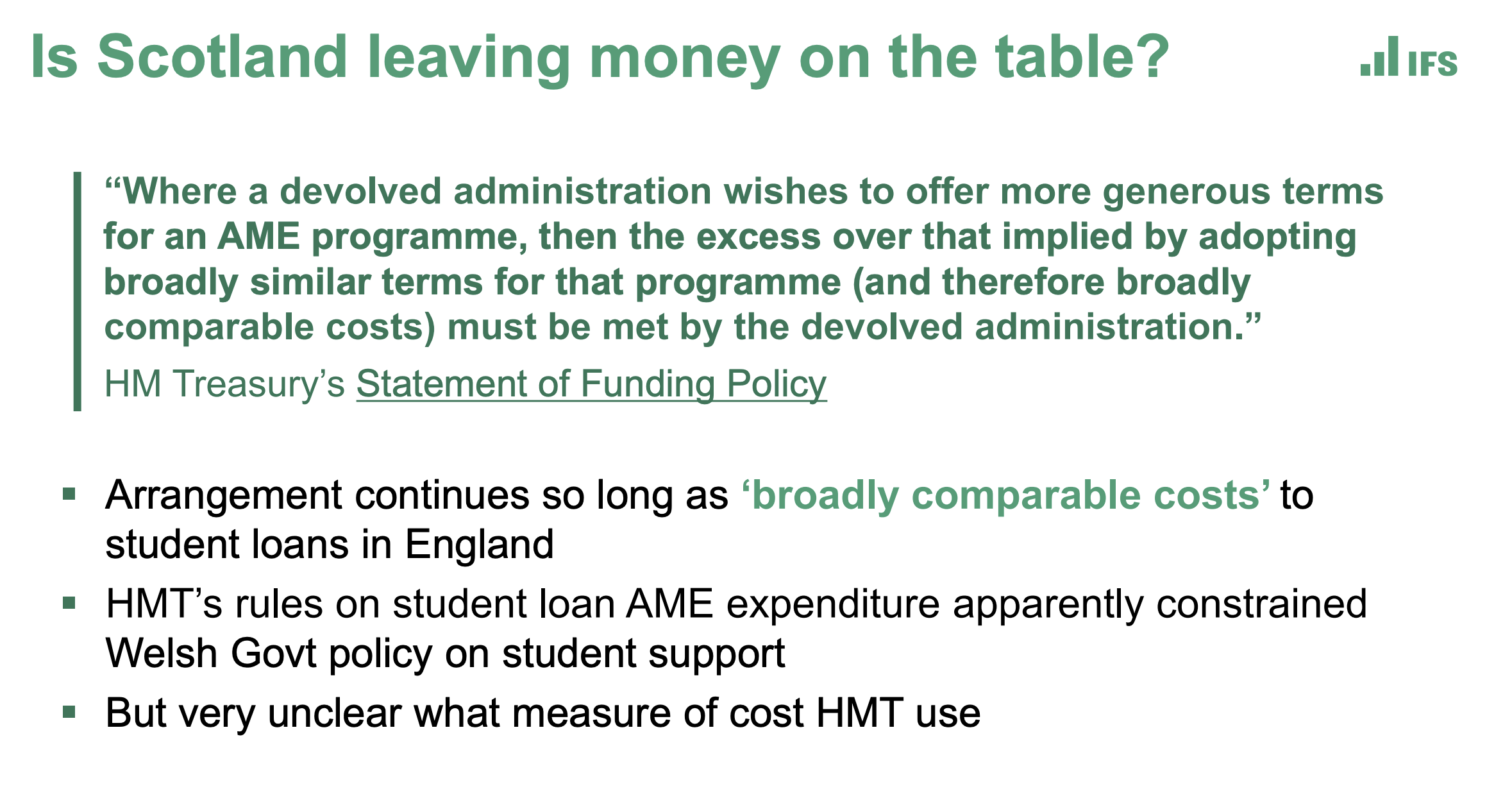

Student loans in the UK sit in annually managed expenditure (AME) – spending that moves with demand and is re-forecast at each fiscal event. For the devolved administrations, HM Treasury’s rule runs like this.

It will fund their student loan schemes so long as each scheme does not cost more overall than it would if UK Government (i.e. English) loan policy were applied to that nation’s own students.

If you hold cohort size constant, that aggregate test collapses into something like this – for a given cohort, the average total loan per borrower over their course under devolved rules must be no higher than the average total loan that the same cohort would rack up if English loan rules were applied instead.

On the repayment side, the same logic applies. The RAB charge – the expected lifetime loss on this year’s new lending – is funded via Barnett off England’s RAB budget, provided expected write-offs per borrower are broadly in line with what English rules would generate.

If a devolved administration made its loan rules so generous that expected write-offs drifted clearly above the English-rules counterfactual, the excess subsidy would hit devolved departmental expenditure, not the UK pot.

In other words, you can tweak loans and repayment terms, but you can’t make the average balance or the average subsidy per borrower materially more expensive than the English-rules version without paying for it yourself. So what does that mean for Scotland?

On the lending side, there’s headroom. Using IFS figures:

England – average total loan outlay per borrower (fees plus maintenance): £43,400

Scotland – average total loan borrowing per student (maintenance only, no home-fee loans): £35,600 (eh? Oh, four year degrees)

The average Scottish borrower takes on just £7,800 less loan debt over the lifetime of their course than the average English borrower.

Scotland is comfortably within the Treasury comparability test on the lending side. Whatever is constraining Scottish generosity on maintenance, it is not the Statement of Funding Policy.

Then on the repayment side, because they’re borrowing less, even with a higher RAB charge, the long-run cost of the borrowing to HMT is comparable. But borrowing isn’t the full picture. What parents have to chip in matters too.

Meet the parents

Let’s take a household on £35,000 – solidly middle-income, the kind of family that politicians like to say they’re helping – with a student living away from home.

In Scotland for 2025-26, the maintenance package at that income level is a Loan of £8,400 a year.

At the bottom of the Scottish income scale (under £20,999), a student gets £9,400 loan plus £2,000 bursary – £11,400 total. That’s a decent proxy for what the Scottish Government is signalling a student actually needs to live on.

For our £35k household, the gap is £3,000 a year. That’s the implied parental contribution – what the system assumes the family will find. Over a standard four-year Scottish honours degree, that’s £12,000.

In England for the same household, the maximum maintenance Loan for a £35,000 household (away, outside London) is £9,038 – some £1,506 less than the £10,544 a year the maximum reckons they can live on. Over three years, that’s £4,518.

In other words, for this family at least, in theory the Scottish system demands about £7.5k more from these parents, while students get considerably less spent on their actual education. Even if we were trying to get both up to Scotland’s max of £11,400, there’s a considerable extra cost to Scottish families.

In other words, there’s almost certainly headroom under Treasury comparability rules to lend more, headroom to accept higher write-offs, and a maintenance system that implicitly demands more from middle-income parents than England’s does.

The Scottish Government appears to be leaving at least some Treasury subsidy on the table and is choosing to constrain maintenance in ways that hurt many of the families the “free tuition” policy is supposed to help.

Alts are available

Other choices are available. Let’s say we wanted to keep the total that Scotland’s UGs borrow over the lifetime of their course to the England calculation of £43,400.

Students’ associations are underfunded, mental health services are stretched, and the actual experience of being a student in Scotland is eroded year by year. So here’s an idea that would be trivially simple to implement.

Create a Student Services Fee of, say, £1,500 per year. Structure it as a loan, and tweak the terms so that it’s written off after 35 years instead of 30. The money (with differentiated governance) goes directly to fund student services, mental health provision, and students’ associations, and universities put savings into teaching.

“Tuition” remains free. Average debt on graduation is still less than England. The Treasury comparability test is still met. The people who pay more are the highest-earning graduates, years after they leave – and even then, only if they can afford it. This is neither complicated nor radical, and is the kind of thing that anyone who actually looked at the numbers would consider obvious.

Then have another tweak – and change the repayment term to 35 years.

But it would require admitting that “free tuition” is not the same as “free higher education,” that the current system has distributional consequences that hurt the people it claims to help, and that the constraint is a political choice in Edinburgh rather than fiscal rules from London.

A previous version of this article wasn’t really comparing apples with apples – I’ve amended it to be more accurate.

Really interesting analysis, demonstrates that the dogmatic politics of a situation is driving worse outcomes.

Would be interested to see a similar analysis of the situation in Wales, especially as Wales has much lower participation rates, a more generous bursary but less favourable repayments ( if I recall correctly)

What about a family on £389,000?