DfE and the issue of concentration in the financial crisis

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

It’s not beyond the realms of possibility.

Instead of fiddling with the points-based system – the outcomes of which can be very hard to predict – instead Keir Starmer can say that his government has taken control of immigration where the previous government lost it.

The last legal migration white paper in 2018 – The UK’s future skills-based immigration system – sold the points-based system as one that would reduce overall numbers, deliver control and “retain our openness to students who wish to study at our universities” – and that was before Boris Johnson went on to approve the return of the graduate route.

In 2024, 393,125 sponsored study visas were granted to main applicants – 14 per cent fewer than in 2023, but some 46 per cent higher than 2019.

The kernel of the (apparently public) argument between the Home Office and the Department for Education isn’t really about reality – it’s about a perception that the openness has been delivered, but the control hasn’t.

So let’s say that the white paper sets up a cap, and it’s set at, say, 350,000.

Within that headline number, the Westminster government (and, to some extent, the devolved administrations) then have choices to make about distribution.

The point is that once you say that not everyone can come that wants to, you can exercise control over the notional benefits and harms that accompany those that do.

In other words, even if you ignore the graduate route debate, you can set limits within a headline number on level of study, when the course starts, subject, region (or nation) or even by provider.

That type of supply-side reform becomes both attractive and necessary to one degree or another to avoid the clustering of notional benefits and harms.

Australia’s proposed cap on international student numbers for 2025 (limiting new enrollments to 270,000, with 145,000 for universities and 95,000 for vocational education) relies on historical enrollment data to establish institutional quotas, with priority visa processing given to applications within 80 per cent of an institution’s historical intake – all to address housing shortages which critics say have been exacerbated by high migration.

Canada’s cap on international student permits, initially reducing numbers by 35 per cent to 360,000, distributes quotas to provinces based on population and historical intake, requiring all study permit applications to include a Provincial Attestation Letter (PAL) – all to address housing shortages, curb exploitation, and manage population growth that saw Canada add over 1 million new residents in a single year.

It’s much easier to make an argument about unfettered competition for students when numbers are growing, and the assumption is that quality constraints will slow the pace of expansion generally.

But once numbers are contracting – either via currency rates, immigration rules changes or caps – and inadequate quality regulation allows unfeasible numbers boom with impunity – it becomes easier to argue for distributional quotas and rules to prevent particular geographies, subjects, qualification levels or timings from accumulating disproportionate benefits or harms.

Broadly, when demand grows, competition often diversifies to capture different niches, preferences, or geographic areas – a sort of market blossoming. But when demand contracts, the opposite tends to happen – markets consolidate, concentrating supply in fewer hands, fewer places, or fewer formats.

A boom in veganism doesn’t just result in more vegan products, but in a wider range – vegan snacks, vegan meats, vegan cheeses. As appetite for digital content grew, platforms like Netflix, Disney+, and niche players like Crunchyroll or MUBI emerged, targeting specific audiences. The dynamic encourages spread.

When demand drops, markets don’t just shrink – they streamline. Niche products and fringe players vanish, leaving only what’s broadly profitable. In plant-based food, that means oat milk survives, mushroom creme eggs don’t. Streaming is the same – as subscriptions fall, experimental shows and niche platforms give way to safer, centralised content.

So if you enforce an overall artificial cap on demand, distributional controls are the only way to retain a measure of… distribution.

Returning to home

Now let’s think about home undergraduates. I might not have agreed with it, but it was much easier for the free marketeers to make an argument about unfettered competition for students when numbers were growing, and the assumption was that quality constraints would slow the pace of expansion generally.

Taking the caps off home UG recruitment and introducing a helpful loan scheme for PG recruitment in the early to the middle part of the last decade did the growth, and the assumptions were still there on pace.

But the past is a foreign country, and they do things differently there. Whatever the causes, UG participation seems to be flatlining, and PG participation falling.

Back in 2019, the Augar panel assumed that the sector could cope with a freeze in fees on the basis of operational gearing – once fixed costs have been covered, the marginal profitability on incremental sales is much higher than average:

The golden zone between covering fixed costs and needing to add costs to cope with extra demand is very profitable; the reverse is true when numbers decrease.

But the panel missed four things. First, the freeze lasted longer than it envisaged. Second, the huge inflation crisis. Third, a huge spike in demand from international students reduced pressure to actually match demand with supply and make incremental efficiencies.

And fourth, while extra demand tends to be distributed widely, reduced demand isn’t as uniform in its distributional effects – it tends to end up with concentration.

That’s what we’ve been seeing at both module level and subject level inside universities, and that’s what we seem to be on the verge of at provider level.

In other words, if the past couple of years have seen redundancy rounds partially aimed at supply choice consolidation on the basis of viability inside universities, eventually you end up with consolidation on the basis of viability between universities.

Or put another way, first there’s too many module choices inside a programme. Next, there’s too many programme choices within a provider. Eventually, there’s too many provider choices within a country.

At some point, if you want to avoid subject deserts, or want to encourage people to study more locally (because it’s cheaper for them and cheaper for the state), or if you want to retain the economic benefits of having a university in a given city, or if you want to avoid the clustering that at least leads to the perception of unnecessary rent-price inflation, you have to either enable profit on the popular to enable cross-subsidy into the less popular, directly subsidise less popular subjects or providers, or engage in some supply-side distribution controls.

And given that there seems to be no desire to (re-)enable profit on the popular, no money around to heavily subsidise less popular subjects or providers, what you have left is engaging in some supply-side distribution controls.

Ironically, most of the public still believe that most student places are scarce and rationed and that “getting in” is an achievement in and of itself, when the reverse is increasingly true – hence the same old headlines every clearing. In fact, the dawning realisation that the scarcity myth is, in fact, a myth is a good chunk of the reputation problem that the sector faces.

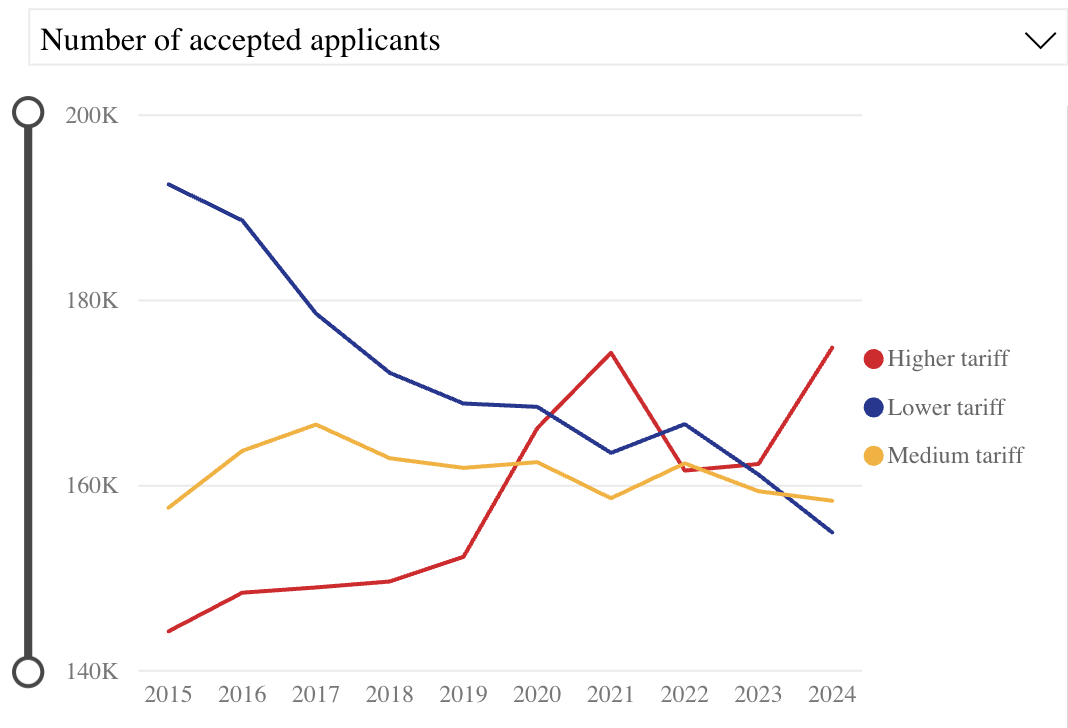

Distribution controls come with the downsides of ministers appearing to wage war on choice, and the fear that the Treasury will choke off overall numbers growth. But the alternative is the recent direction of travel in this graph reaching its natural conclusion. That’s the real choice facing the Department for Education and its devolved counterparts right now.

(UCAS undergraduate applications placed by provider tariff group by end of clearing)

It’s easy to see that graph as a fundamental reshaping of demand if your public policy interventions are all about influencing demand. It’s the sort of mistake that papers like this make, with its dated focus on improving information so applicants can make better choices. Once you understand it as a fundamental reshaping of supply, you have more options. They’re options you need if you want to avoid, for example in Wales, USW going first, eventually ending up with Cardiff as your only university.