An increase in maintenance loans gets blunted by fiscal drag

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

But it’s not as generous as the 3.1 per cent increase to fees is for universities.

Today Bridget Phillipson said:

I therefore confirm that we will boost support for students with living costs by increasing maximum maintenance loans in line with inflation, giving them an additional £414 a year in ’25-26.

The “them” in that sentence is students away from home in London, which even seems to have succeeded in misleading the IFS. It’s actually £267 for those at home, and £317 for those away from home and outside of London.

It’s worth remembering that as well as home/away and London/elsewhere, two things determine how much a student can borrow – there’s the maximum headline amount, and then a household income threshold over which parents are expected to make up the difference.

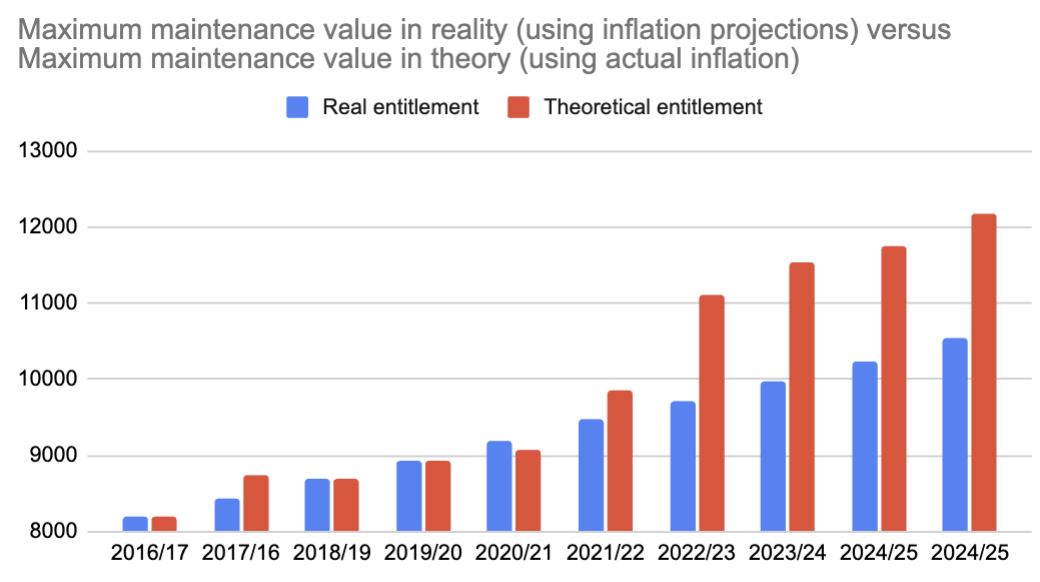

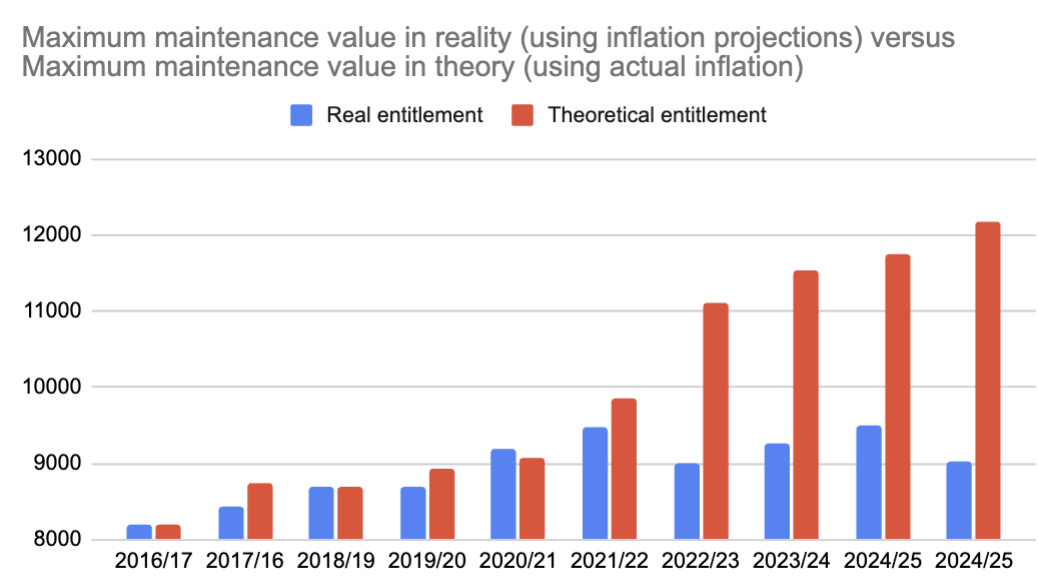

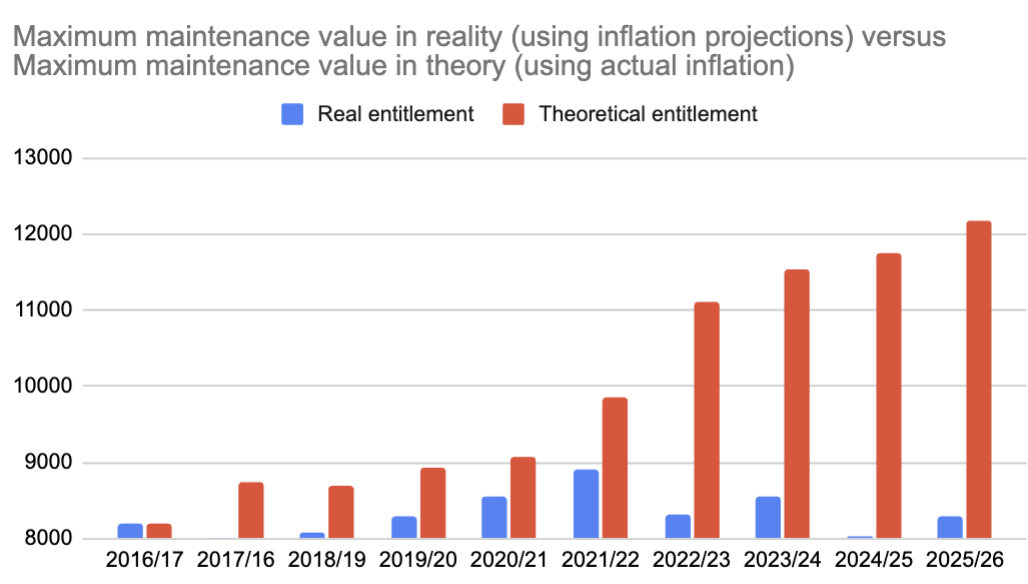

The former of those has for a long time been uprated by using the OBR’s RPIX projection for Jan-Mar of the academic year the student will be paid in. The problem there is that the OBR consistently undershot its inflation guess – and there’s been no mechanism to correct that.

The latter of those has been fixed at £25,000 since 2007 – and so acts as a considerable fiscal drag on the amount that a student can borrow.

It’s worth remembering that from Apr 2025, a single parent on minimum wage doing a 40 hour week will earn over that £25,000 threshold. 25k is also the repayment threshold – so grads in that position will start repaying immediately.

So the “them” who get the full loan has been declining as a proportion. Here’s the number and proportion of FT students that actually received the maximum student maintenance loan outside of London in each year since 2012:

Here I’ve updated the modelling I did back in September to look at the impact of both of the issues. Taking 2016–17 as a baseline (as that was when George Osbourne abolished grants) I’ve looked at three families and modelled the inflationary increase that DfE applied versus the real one that kicked in, and updated the earnings of three families:

- Family A, who were earning £25,000 in 2007

- Family B, who were earning £25,000 in 2016

- Family C, who earn £25,000 now

For Family A, you’ll see that the impact has been fairly modest (although huge for that family in context) – they have just been hit by the inflation issue.

For Family B, you’ll see the impact of that family earning more over time – the parental contribution increases over time, generating an over £3,000 gap now:

For Family C – who were earning the lower limit for a full grant/loan when Labour last set the threshold – the impact is even more dramatic. It’s an almost £4,000 gap – add in additional years of study or another child at university (or studying in London) and the impact is pretty devastating.

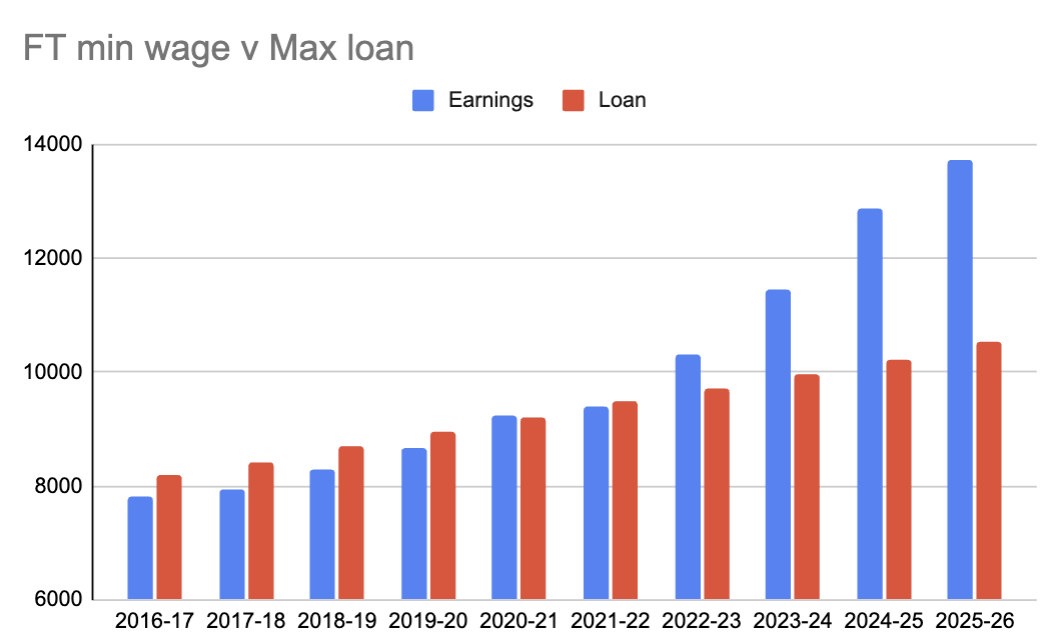

It’s also worth considering the issue from the perspective of the ability to make up the shortfall. Here I’ve compared the max loan (outside London and away from home) with the minimum wage, ignoring the under 21 age bands.

For comparison we’ve used the Wales/Augar calculation of 37.5 hours a week for 30 weeks as the number of hours that students are theoretically prevented from accessing earnings in the Labour market because they’re studying. I’ve applied the 21 year old rate for each year:

Put another way, even if we compare a full-time 21 year old on the minimum wage with a full-time student for 30 weeks a year who earns an FT minimum wage for 22 weeks a year, there’s an over £3,000 gap – and students are borrowing a good chunk of that income.

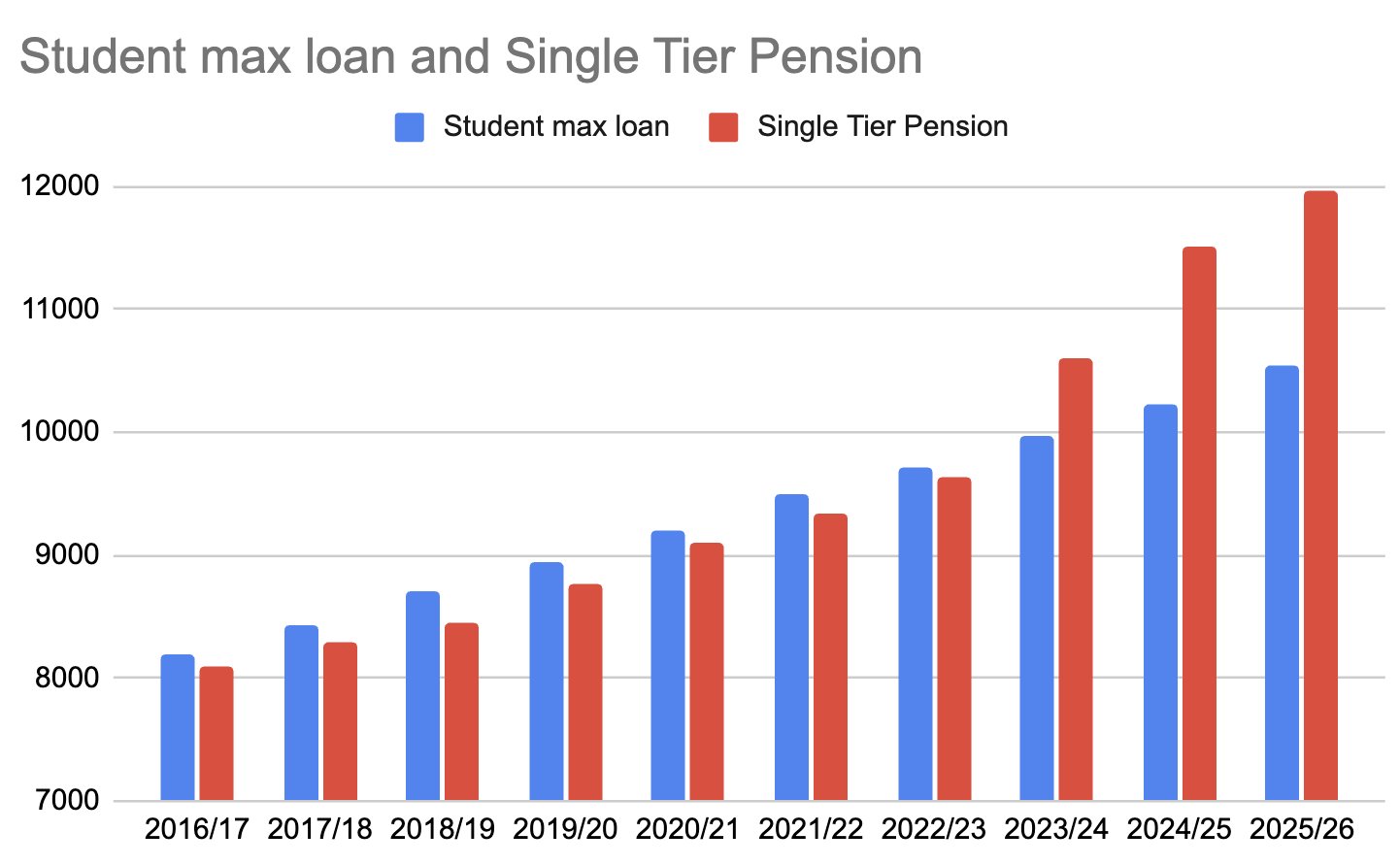

Finally, just for “fun”, let’s compare Single Tier state pension (STP) rates with the maximum (away from home, outside of London) loan rates:

Students never got a winter fuel allowance to cut, of course.