All must have prizes (except Iain Dale)

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

The comment is in a short blog from Dale in response to Galbraith’s comments in a Sunday Times piece which carries the headline:

Rapid Russell Group expansion ‘puts smaller universities at risk’.

Galbraith kicks off by arguing that uncontrolled expansion is a concern, and that there needs to be regulation in place so it does not cause instability in the market.

If the sector becomes concentrated to a small number of key institutions in cities like London and we lose locally available higher education, is that what we want? There is a danger of that happening, unplanned. Then we will ask, ‘How did this happen?’ when it was blindingly obvious. Some kind of soft cap of 5 per cent annual growth [in student numbers] would make the market more stable.

He then addresses the student choice argument that’s usually deployed to justify the absence of any controls on student numbers:

People have said ‘but what about student choice?’, but I am concerned about student choice in 2040 onwards and keeping a sector that provides choice long-term, and not letting the big players take the others out. There is a risk of a monopoly in the market.

Dale seems very upset at the idea that “top grade” students should, in some cases, not be allowed to go to a Russell Group university, and instead be allocated to him:

All universities have a reputation and you can only build a reputation over time, yet Professor Galbraith appears to think his institution should be given a leg up through penalising the success of the universities higher up the league table. It’s the ‘All Must Have Prizes’ ideology, which I thought we had despatched to oblivion. Not in Portsmouth, it seems.

There’s a particular irony in Dale’s position. He rails against “All Must Have Prizes” while defending a system where Russell Group universities appear to be doing exactly that – using their brand prestige to hoover up students while relaxing the entry standards that supposedly justified their elite status in the first place.

With a relatively fixed pool of applicants and a relatively fixed distribution of A-level points, if “top” universities are expanding their intake, they’re inevitably either reducing the attainment of those they admit, or redistributing market share at smaller institutions’ expense, or both. Maybe it’s not “All Must Have Prizes”, but it’s certainly “More Must Have Russell Group Prizes”.

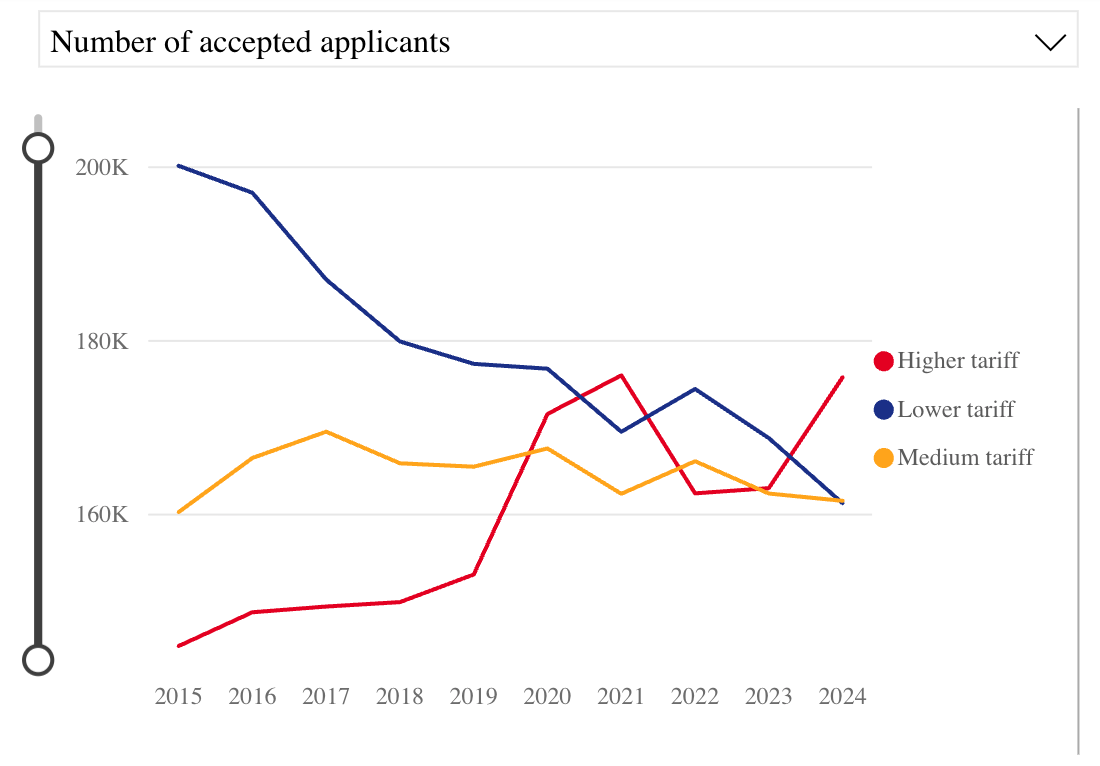

The piece in the Sunday Times makes judicious use of UCAS figures – which last year brought us this graph 28 days after Level 3 Results Day:

On the assumption that the “higher tariff” group hasn’t changed (because it would make the year on year comparisons faulty if it had), what we can say is that however high that tariff was, it’s getting lower. Does Dale know that universities in that red line are routinely accepting students 3 or 4 grades beneath their published offers?

Arguably Galbraith is actually calling for some basic market regulation to prevent monopolistic behaviour. Dale’s framing of it as wanting a “leg up” rather than asking for fair competition rules suggests he has a fundamental misunderstanding of how markets work.

You can just as easily argue that “high tariff” providers are the ones getting an unearned advantage – using brand prestige to expand without proportional investment or improvement, while smaller universities face the choice of either competing in an increasingly rigged game or watching their student base erode.

Part of Dale’s argument, for example, is that Galbraith should make Portsmouth…

…as good as Durham, York and the rest, and then perhaps you’ll be able to attract students on your own merits. It’s not as if his university isn’t on the up. In the rankings Portsmouth has gone up from 65 to 55 over the last twelve months, so clearly things are improving.

There Dale uses league table position as a proxy for quality – as if the tables aren’t questionable. He’s referring to the Sunday Times 2025 Rankings – which actually had Portsmouth at 29th for teaching quality (Durham 54th, York 94th) and at 24th for student experience (York 65th, Durham 83rd).

Where Portsmouth couldn’t compete was in research quality or entry standards – or on the hurling out of more firsts and 2:1s, which presumably would be another example of “All Must Have Prizes” if Dale bothered to interrogate the tables.

Galbraith goes on:

Maybe we do want fewer institutions, I don’t know, but there needs to be a conscious decision made about the kind of sector we want…It’s not going to get cheaper going to university and that is already starting to drive more people to taking up places locally, so we shouldn’t be taking away options in their locality.

Interestingly, as well as the usual lament about the abolition of the binary divide, in Dale’s blog we get a reference to 1979 – when he recalls considering applying to what was then Portsmouth Polytechnic to do a German degree:

In those days it was in what was the equivalent of the Russell Group of polytechnics. It did exactly the kind of course I wanted to do, but in the end I decided to go to UEA, but not because UEA was a university.

How lucky Dale was to have the choice. UEA now only offers French, Japanese or Spanish on its Modern Languages degree – in that scenario, we may never know if he’d have chosen York (“which also offered me a place”) or Portsmouth.

In fact one of the points Galbraith is trying to make is that it’s already getting very hard to study Modern Languages outside of the Russell Group, and will be even harder if a university like his disappears.

Most vexing of all, really, is the lazy elision between the top end of the league tables and the Russell Group – not because the tables are statistically problematic and based on one particular idea of what constitutes a “good” university (they are), but because the latter isn’t like the Premier League – it’s literally a closed group. One thing that Dale is right about is that it’s hard to see the “higher technical” in a system where everything’s a university, and that in a mass system, choosing the right course in the right university is difficult – the problem is that apparently unlike Dale in 1979, what a lot of applicants do is choose the university that’s the highest up the table they can afford with their UCAS points.

After all, the fees might be fixed, but points at Level 3 are pretty much a proxy for family wealth. Without controls on places and a DfE that thinks of university as an extension of school, we’re left with a situation where the public assume that lots of provision is substandard, and lots of its graduates too. With the degree classification system left meaningless, RG is now the go-to proxy for “good”. How sad.

The truth about this silly spat is that Galbraith is right when he says that there needs to be a conscious decision made about the kind of sector we want.

Even if you think it’s a jolly good idea for there to be fewer universities in the UK, a conscious plan would involve ensuring there were enough personal tutors, seats in lecture theatres and rooms to rent around the Russell Group, and a plan for already beleaguered towns like Portsmouth and its region – one that will ensure that those already in aren’t mugged off with endless reorganisations, and one that ensures that those priced or Disabled out of leaving home to go to university can still access higher level learning.

I predict that the UCAS application figures for 2026 entry will again show an increase in applications for Russell Group Unis and equivalent – as teachers, applicants and parents know they can get in with good to average grades, aided by potentially misleading info from a UCAS “average entry grades tool” launched in 2024 and updated in 25 and am arms race of UCAS predicted grades from Schools/colleges. Will the quality of teaching and student experience at those “high tariff” Unis be of high quality and match the brand perception for those students arriving in 2025 and indeed last year… Read more »

The brand value = R output as the dominant factor in the methodology used in the global rankings/league-tables = tells little about T quality to the applicant because the rankings methodology finds it difficult to measure T as a mystery ‘black-box’ process. The TEF helps a bit as a corrective for the fixation over the REF. Yet, of course, the brand label ‘elite’/‘top’ sends a signal to potential employers who also can’t readily assess what the graduate gained from the degree course.

The UCAS tariff groups change each year according to the average UG tariff of accepted applicants in the previous UCAS cycle. More being accepted to higher tariff providers means that last cycle these providers could not have routinely accepted lower grades or they would no longer be classed as higher tariff providers. Time will tell if next year’s graph reads the same trend or if providers have been cutting their grades and then more will fall into Medium and Low groups next year.

UCAS keeps each group as approximately one third of providers. So if average higher group tariffs are falling, it is likely that other tariffs are falling too leaving the groups pretty similar.

One of many reasons why provider tariff groups are a waste of time.

Free markets always collapse into monopoly or cartels. The Russell Group is the latter, of course, and very happy with the prospect. Student choice is not a genuine concern when money is on the line and raising it as an issue is simply deflection from the true motivation. Dale must think we were all born yesterday.