There are too many people doing “poetry and painting in a poly”, said a Conservative backbencher to me over the summer. “It’s a waste of money for them, and a waste of money for the taxpayer”, he said, and “they’ll blame us for life when they get their student loan statement”.

So, I asked him, would you cap places to do poetry in post-92s? “Oh no”, he said, “we’d look like the enemy of opportunity. Far better to make the alternatives attractive.” But what if that doesn’t work? The “market” in HE involves pumping applicants full of data about future salaries – but what if, even with that data, people still choose “poetry and painting in a poly” away from home, over “earning and learning” in their local area?

On the other side of the green benches the usual thing to do is to complain about “marketisation”, manifesting itself in unconditional offers, unscrupulous advertising and grade inflation. All of these symptoms are ultimately the impact of removing the numbers cap, driving up competition and allowing supply to run ahead of demand. But it’s really hard to find someone who would advocate supply-side caps to get on top of the problems – because no-one (not least Labour’s Gordon Marsden) wants to be seen as that enemy of opportunity.

If the debate over Labour Party Conference’s proposed cap on private school entrants to university tells us anything, it’s that it’s really hard to say “no”. In this iteration, the Headmasters’ and Headmistresses’ Conference said universities could be forced to “shrink” departments such as modern languages as a result, with plenty of alarmist coverage in the sorts of papers that frame anything that comes out of OfS’ Chris Millward’s mouth as a “cap”.

These are the sorts of questions we’ll be debating at Wonkfest – including with England’s Universities and Science Minister himself, Chris Skidmore – whose principal public intervention during the Augar process was public rejection of a floated proposal to say “no” to those with 3 Ds or below at A level.

The alternative to saying “no” (and looking like an enemy of opportunity) is saying “yes” to the alternatives. Blairism tried to deal with the public/private schools disparity by promising to “level up” the quality of state education, seemingly to no avail. And right now on the artificial vocational v academic divide, Education Secretary Gavin Williamson’s tactic is the same – don’t admit to wanting to cap traditional university places, but instead attempt to argue that vocational alternatives can be “levelled up” both in terms of funding and esteem.

One problem

The trouble is, without some “saying no” caps, these approaches look doomed to failure – especially over the next decade. Take what we might call OfS’ “KPM 1 problem”. Last December when OfS launched its revised access and participation regime, you’ll doubtless recall “Annex D” on the development of access and participation targets. Its “Key Performance Measures” set out ambitions, then its “Targets” set out collective milestones to realise those ambitions.

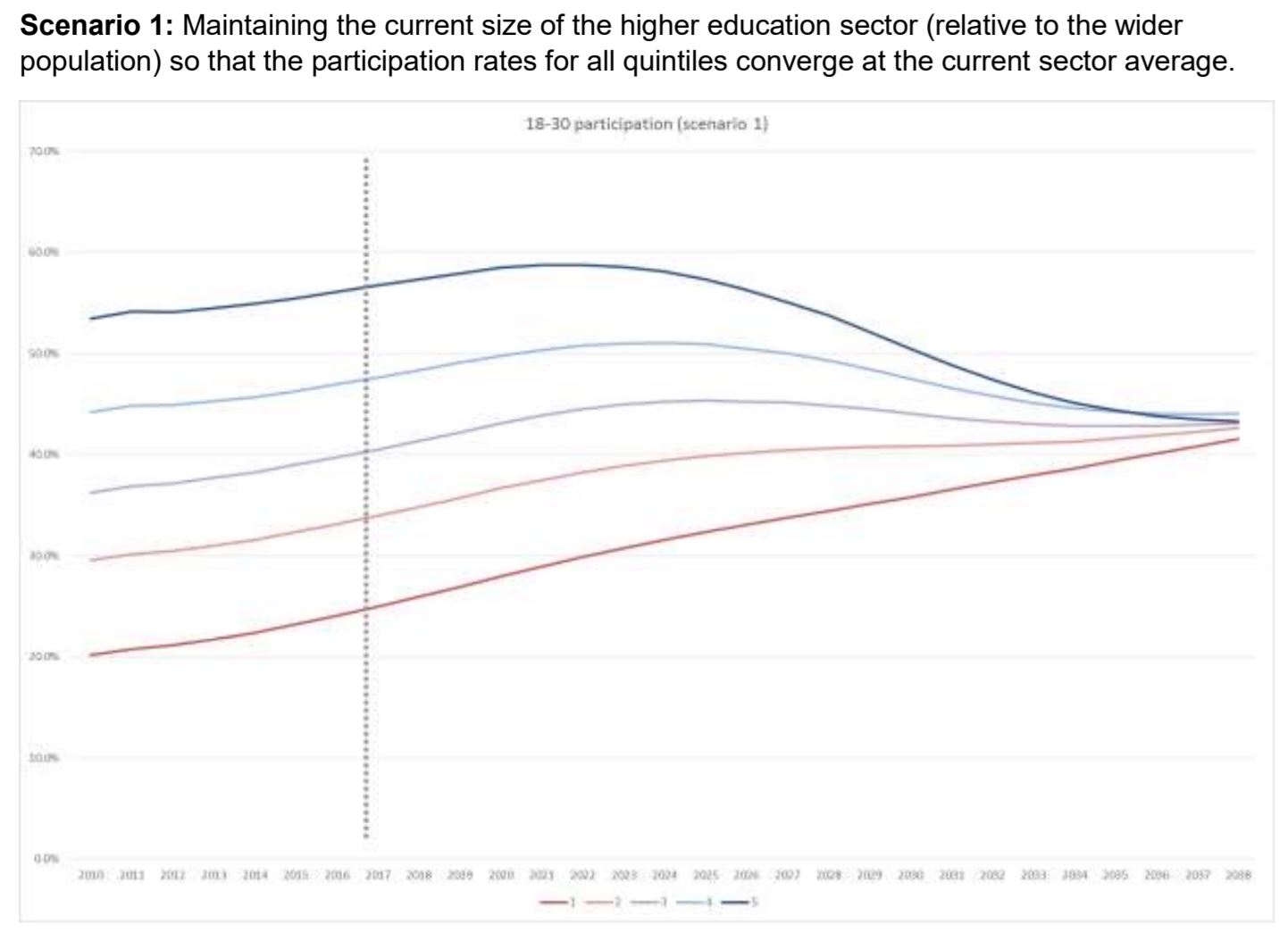

KPM1 – closing the gap in participation between the most and least represented groups – was proving to be tricky. “There are significant external factors that would critically impact on the achievement or otherwise of any target we set for this KPM”, said the paper. A couple of graphs explained why. In its “Scenario 1” to equalise POLAR we’d have to say “no” to a whole clutch of POLAR 5 parents – taking their kids’ participation from about 60% to around 45%. It’s a scenario that’s both politically unpalatable and fiendishly difficult without active POLAR caps (or proxies like the Labour Conference proposal).

In its “Scenario 2”, you equalise by expanding – effectively keeping the participation rate where it is for POLAR5, and increasing the rate for everyone else. This would involve increasing the size of the sector by about half over the next 10-20 years. And that’s on top of the size of the sector growing naturally, with dataHE putting that pressure at having to duplicate by 2030 the current 35 largest English recruiters of 18 year olds.

At the time of writing we can safely assume that OfS assumed we’d have a response to Augar by now – but here we are in October 2019, with a fresh batch of approved 5-year Access and Participation Plans published on its website, and only a vague promise that the Augar response will be out this winter. OfS’ collective target in pursuit of its KPM will only be known once they’re all published, but it’s safe to assume that even with plenty of pressure being applied in APP approval ping-pong, it’ll be some way off POLAR equalisation – and even then “ambitious” plans will be assuming numbers growth to get there.

Public pressure

Numbers growth has always been the way the sector has avoided going bankrupt, but this time round it’s a problem. Our middle class kids love leaving home at eighteen, but our current university towns and cities look “full”, with real pressure on populations and housing costs. Economic and social bifurcation between places with a university and those without is starting to look deeply undesirable. Toby Young and co think that more than half of England’s 17-30 year-olds are “bug-eyed anti-capitalists” enrolled in “left-wing madrassas” that do things like electing a Labour MP in Canterbury.

But discouraging young people from the residential experience looks deeply problematic, because we know who we’d hit. Research for the Sutton Trust last year found that over three times more students in the lowest social class group commute from home than do so from the highest group. In other words, leaving home and attending a distant university is too often the preserve of white, middle class, privately educated young people.

And controlling for factors like class, location and attainment, state school students are almost three times more likely to stay at home and study locally than their privately educated counterparts. Choking back residential would surely exacerbate the split – meaning that the rich leave home and “find themselves” whilst the poor leave home and “find” a local bus route.

What are we producing?

Left alone, we’ll allow an expanding middle class to soak up growth, topped up with APP interventions to give more people the residential experience. But how many more “traditional” graduates do we need? Right now we aren’t producing enough “higher level” vocational graduates with a global economy AI-ing its way out of the need for generic grads that can write essays. And loans for tuition and maintenance now appear on the books when they’re made – or in a Labour future, all of those costs – and outside of our bubble, the public want investment in schools and hospitals.

As the cost ratchets up and up and the bifurfaction gets more intense, you have some options:

- You could say “no” to current university growth altogether, letting further education grow to soak up demand as polytechnics did when universities were capped in the 80s;

- You could say “no” to any more university growth in current locations, allowing expansion into other places with all the economic and social benefits that would bring;

- You could say “no” to any more “residential” places at universities, causing colleges and universities to become more comprehensive as they rush to make commuting more normal;

- Or you could say “no” to “low value” courses, on the assumption that supply and then demand will flow into “high value” ones – if, of course, you can find a credible way of differentiating between the two.

But all of those options require vision, and capital, a big majority and saying “no” to people who want to leave home and do poetry and painting in a poly. There will – quite rightly – be plenty of lobbying against all of those options. And if your alternative is just… incentivising the alternatives, there’s too many factors – social, economic, political, and geographical – that get in the way of rationally believing you’ll be successful.

So if it’s unlikely that we’ll see someone saying “no” out loud, the demographic demands go the way we think they will, and politics remains chaotic, your only other option is to quietly and subtlety choke down the unit of resource. You ensure that the total student funding package will eventually price plenty of people out of leaving home, but put pressure on your access regulator to look busy as a counterweight and throw in some fig-leaf grants. You freeze the resource unit in today’s money in perpetuity, but put pressure on your regulator to hold providers to standards that eventually many won’t meet on the money they have – and you make it easier for students to sue for broken promises in the process. Class sizes increase, module choice contracts, and the personal contact that students crave collapses.

The irony? That anyone that thinks that this could happen in the future might be ignoring quite how easy it has been to engineer in our present.

Wonkfest runs 4-5 November in London, and tickets are available. Universities and Science Minister Chris Skidmore will speak in conversation with Mark Leach on Monday afternoon.

‘Sorry’ is the hardest word in education policy, Jim.

‘Right now we aren’t producing enough “higher level” vocational graduates with a global economy AI-ing its way out of the need for generic grads that can write essays’. This type of casual claim is deeply worrying from somebody writing about HE with supposed knowledge. You don’t have to argue for the need to up the number of people studying/working with AI by making an ill-informed tabloid-worthy statement about ‘generic grads that can write essays’. Anybody who knows anything about studying the Humanities and Social Sciences should not reduce so flippantly the worth of those studies with poorly articulated statements like… Read more »