This week The Daily Mail has published a two-part investigation into fundraising practices, and specifically into the business of researching potential donors to universities. Once again I was saddened by the vitriol with which my industry was being attacked.

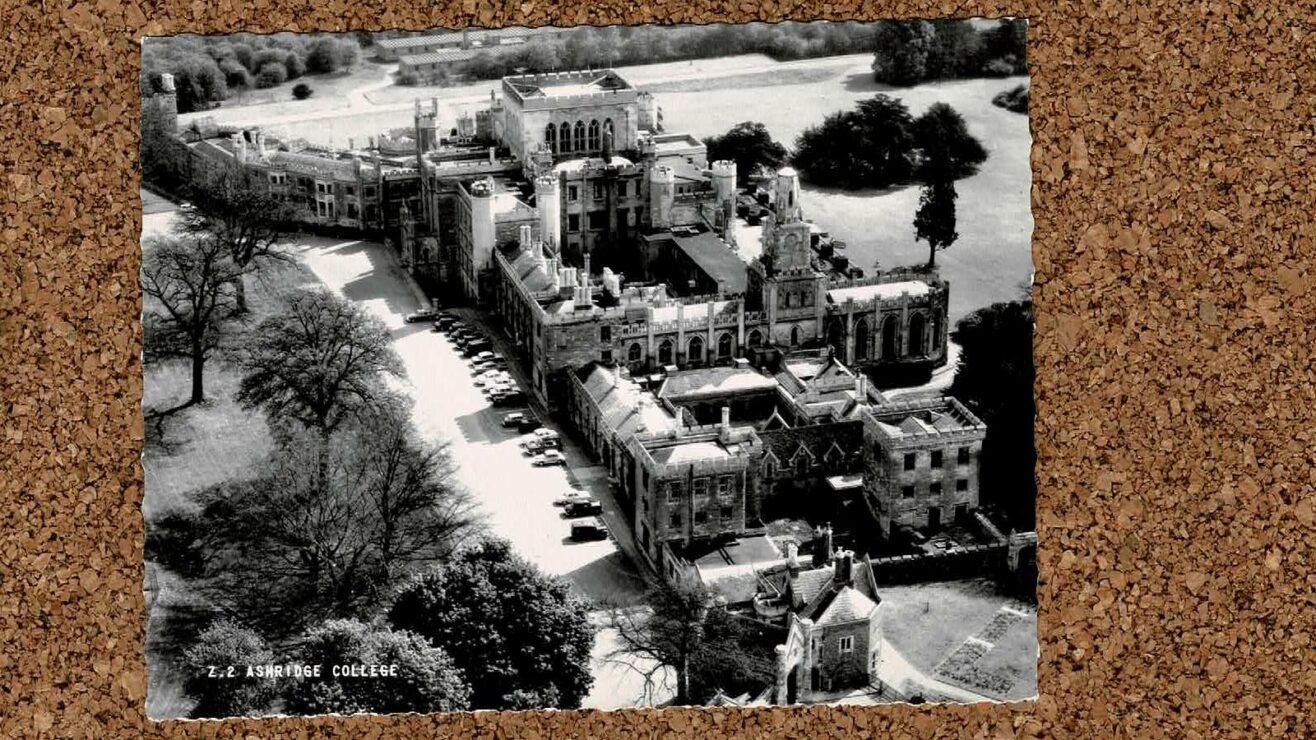

I have been what the press has called a ‘wealth researcher’ – or ‘prospect researcher’ – for over 10 years. I started my career at a Russell Group university, passionate about supporting higher education in the UK, and determined to move our capability and our progress forward.

Alumni are a logical first choice for university fundraising. They (for the most part) are likely to have fond memories of the time spent at their alma mater. For those that have done well in the wake of receiving their degrees, giving back to their university can be a way of saying thank you, and to not only help future generations to learn and to achieve as they have done, but to make a real difference by funding the vital research that all universities carry out. From pharmaceutical and engineering inventions, to animal welfare policy – the insight that comes out of our higher education institutions is ground-breaking and invaluable to society.

But how do you go about asking an alumni-base of hundreds of thousands of individuals for money in a way that is cost-effective? Sending a letter is indeed what many may have chosen to do in the past – but imagine the cost of printing and mailing something to the whole community? It goes some way to negate the money that is eventually raised.

Adding intelligence

This is where my role comes in. Our job is to identify those individuals who are both more capable and more likely to give back. Imagine you have 500,000 individuals on your alumni database – the cost to mail everyone would be extremely high. Now imagine that with the expertise of a researcher you can identify the select a few that may be more welcoming of the communication. Not only will the fundraising costs be minimised, but eventual income is likely to be higher because of the intelligent targeting behind the campaign.

Prospect researchers are not just wealth researchers however, they are data protection gurus. We all abide by a code of conduct published by the UK Institute of Fundraising, and we adapt our practices as laws and guidance change. We know what data should not be collated and what should not be recorded. The data that we do use is only ever ‘out there’ for anyone to see in publications and on the internet. Contrary to some commonly held beliefs, we do not have access to anything that that the public couldn’t see should they want to.

The difference is that, using our expertise, we are able to see the bigger picture of the data we do have access to. We can interpret it and make assumptions based on what we do know. Do you potentially have the capability to give a larger gift and, more importantly – would you possibly want to? We will never know what you have in your bank accounts. We don’t know what your outgoings are. We do not have access to your private financial dealings or your personal lives. What we can see is what everyone else on the internet can see about you.

Data and algorithms

The companies such as Prospecting for Gold and WealthEngine mentioned in the Daily Mail article use computers to do exactly what prospect researchers do manually. They collate this information and give universities and charities an indication of wealth only based on the running of algorithms to analyse the data. I worked for WealthEngine for three years.

The aim is not to spy on you, but to understand you. Think of the data your favourite supermarket loyalty card collects on you every time you shop. They use this data to send you vouchers for your most purchased items. They get to know your habits, they understand what purchases you need and what makes you tick, and attract you back to buy more with offers.

Prospect research is not dissimilar to this. We get to know you, as much as we can, so that we won’t bother you unnecessarily with charitable initiatives that will be of no interest to you and, on the flipside, present to you opportunities that may really pique your interest.

The profession has been criticised in the press several times in the past few years and with every new furore that arises we pick ourselves back up, listen to rulings and to guidance and adapt. We abide by the law – but the issues we face are not confined to the non-profit fundraising industry. Data breaches happen every day. Passwords and financial details are stolen from websites, unprotected laptops are left on public transport. All universities and charities have accessible privacy policies that are clear about what your data will be used for, and clear about how you can opt out of this.

We do what we do to make the money you generously choose to give go further, to help more of it reach the causes that you want to support and we’re proud to be the profession in universities that enable those differences to be made.