Apparently, students are “shunning university digs” for “home comforts”.

Setting aside the increasingly anachronistic use of the word “digs” to denote living away from home while at university, the story in the Times is a familiar one – it’s the idea that thanks to concerns about costs, where once students would flee the nest to go away to university, now they remain at home and commute to campus.

As well as comments from UCAS chief executive Clare Marchant on UCAS’s own research on student awareness of the realities of the experience, the story is underpinned by figures from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) which the Times says reveal that the gap between the number of students living at home and going away to university has narrowed to fewer than 100,000 – down from 250,000 in 2014-15.

It says that data shows that about 850,000 students lived away from home in 2014-15, compared with 586,000 who remained at home. But by 2021-22, there were supposedly 946,000 students away from home compared with 850,000 at home.

The problem, of course, is that while the never-explicitly mentioned imagined student in the piece is the home domiciled 18 year-old that has just completed their A levels, HESA’s figures include international students and postgraduate students.

So to try to work out what’s really going on, we asked HESA to break out international from home, and resolved to look in detail at what has been going on with postgraduates.

Can you understand me now?

First up, let’s take the full-time undergraduate floating around in the subconscious of the Times readership.

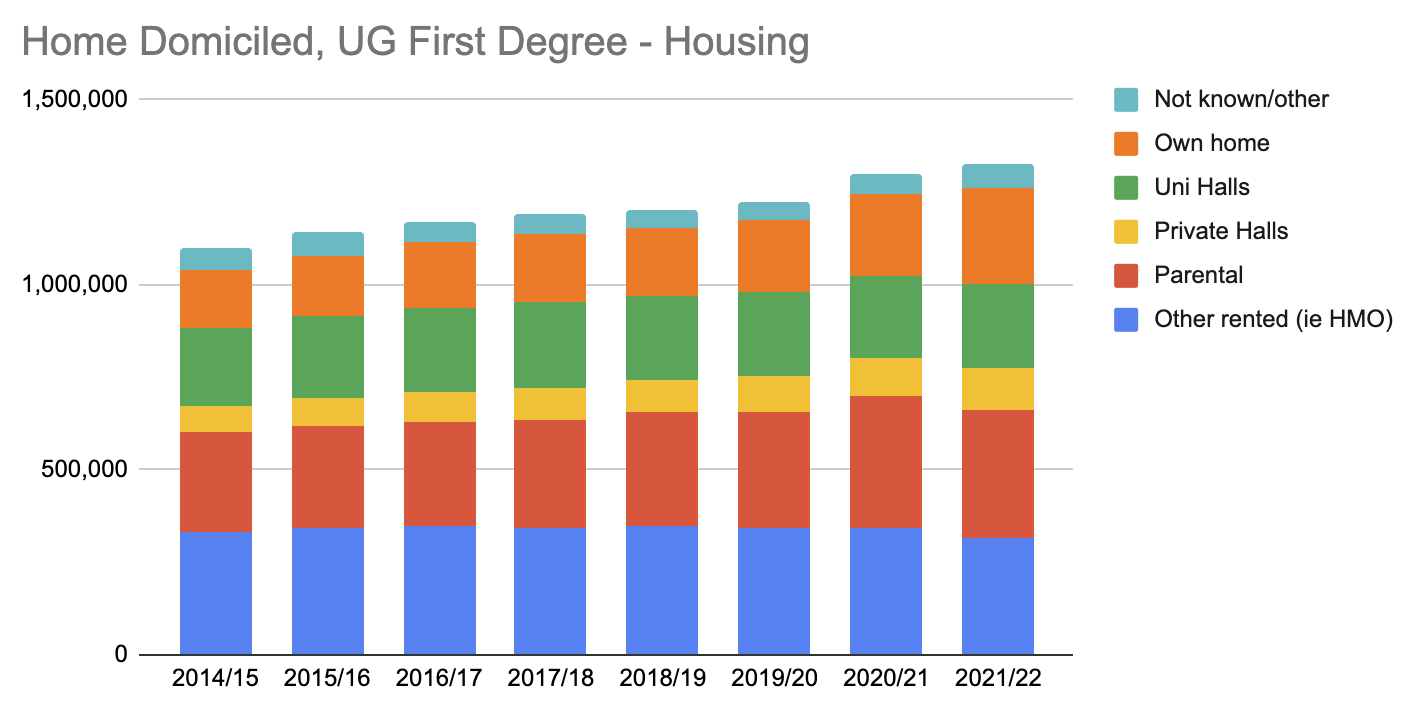

HESA’s figures for full time, first degree home domiciled students (excluding students enrolled with Falmouth and London South Bank) tell us that we’ve gone from 1,039,910 in 2014-15 to 1,260,705 in 2021-22 – and across that period we’ve gone from 59.2 per cent of students living away from home to 52. 4 per cent.

That is a gap of 190,400 in 2014-15, narrowing to 60,935 last year. It certainly feels like quite a trend.

But caveat time. Not known/other saw a spike in 2020-21, living in the parental home shot up by almost 50k that year, and living in a shared house (HMO) dropped 20k last year to an all-time low of 317,455.

These feel like pandemic impacts – students starting at or moving home, and to some extent staying put once there – and if you accept that narrative, the question that remains is the extent to which those trends continue into future years.

It’s worth working out what’s going on with first year (full time, first degree) students just to confirm the trend. There 61 per cent (of those whose living arrangements we know about) were living away from home in 14-15 – crashing down to a low of 51 per cent in 2020-21 and bouncing back a bit to 54 per cent in 2021-22.

It’s a substantial number of students – and aggregate figures hide all sorts of local variation – but it doesn’t feel as significant as the narratives suggest.

But then we look at international students.

I’ll get it through somehow

As Debbie McVitty points out elsewhere on the site, the latest polling for Universities UK suggests that while the public is worried about entry to the UK via small boats crossing the Channel, it remains not especially fussed about international students coming to the UK to study. Vivienne Stern, chief executive of UUK, says:

The public understands the enormous contribution that international students make to our economy, institutions and research outputs, as well as enormously benefiting the UK’s international reputation. Our international institutions are cherished by the public, and we would hope that government policy follows suit.

That reflects the central narrative that the sector tells itself has about the impact of international recruitment. But like everything that the sector says on international students, there’s little on the impact on communities generally or on housing specifically.

Yet there have been significant and dramatic increases to the international student population in recent years – and they have to live somewhere, in a country where talk of a rental housing crisis is common. So what’s really going on?

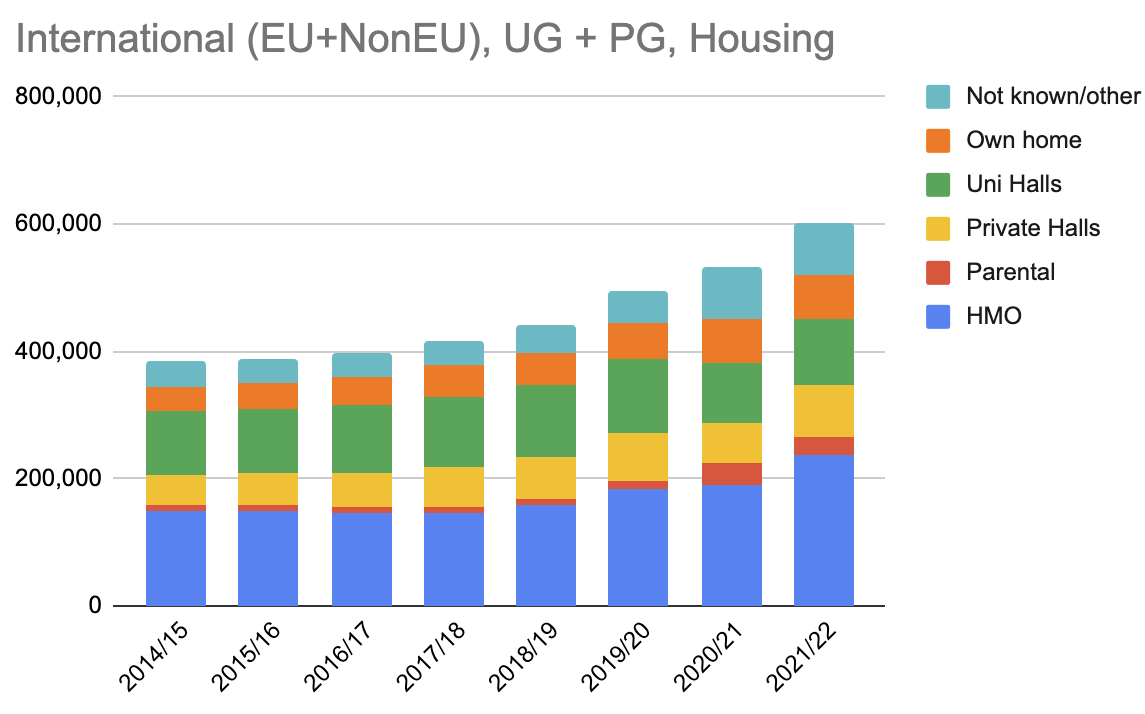

If we add up all of the FT international students that we know about – PG and UG, EU and non-EU, first degree or not, we went from 385,485 whose living arrangements we knew about in 2014-15 to 601,985 in 2021-22 – with about half of that increase rammed into the final two years of that period.

That much we knew already from general stats on international PG expansion, and stats from the Home Office on visas issued to students and their dependants. What we’ve not understood is where they’re living.

Over the 2014-2021 period that we have figures for, the number of international students whose living arrangements we know about increased by 57 per cent – almost exactly the same as the rate of growth of international students in HMOs over the period.

That’s true too of private halls – where 45,200 in 2014-15 to 80,130 in 2021-22 is a similar growth rate. Part of the overall problem is that the stock of university halls beds hasn’t increased much for international students – that was just over 100k in 2014-15 and virtually the same last year.

But other than that, the proportion of international students living in each type of accommodation has remained really quite consistent.

Won’t see me hanging around

What that results in, if you expand international a lot, is a shift in who lives where – because international students generally can’t choose to live at home.

If we look only at “other rented” (principally HMOs), the Home v International share has shifted 71 per cent Home / 29 per cent International in 2014-15, to 60 per cent Home / 40 per cent International in 2021-22 – with the bulk of that shift taking place since the introduction of the graduate route and the rapid expansion of the number of international students in the UK.

So if expansion continues at the rate that it has been over the past couple of years, what already feels like a student housing crisis can surely only grow.

Again, the aggregate figures smooth all sorts of local variations – here DK has plotted an interactive that allows you to play with the parameters to look at your own local story.

A particular caveat is that to properly understand what’s going on, you usually need to look at multiple providers in a city or event region – and the more I hear about international PGTs living very long distances from campus, the more even doing that paints an incomplete picture.

The numbers, when we get them, for 2022-23 will be fascinating – partly because they’ll allow us to see whether some of the pandemic impacts have been temporary or permanent.

But on the face of things, the figures at least suggest some explanations for the sharp shortages of student accommodation that many cities are reporting, the dramatic rise in costs of rental properties that many say they’re seeing, and resultant shifts in behaviour of both home and international students.

Put really simply, the figures support a hypothesis that if you expand international student numbers at a faster rate than the HMO or Purpose Built Student Accommodation (PBSA) markets can keep up with, you overheat the student part of the rental market.

That pushes rents up – with some international students outbidding their home counterparts for local beds, some living in overcrowded housing, and some living too far from campus to make the full-time student experience viable.

For home students, some have the money to stay in the local rental market, but many move home – either after their first year, or never move away in the first place.

Can someone turn the light on?

It is true that international students and their fees are what is making the numbers add up on the excel sheet across lots of parts of the sector. It is also the case that when you look at some providers, the loss of “away from homers” from local HMOs and halls is made up for by international students who don’t really have the choice to stay in the parental home in the bulk of cases.

But it is also almost certainly true, right across large numbers of major university towns and cities, that this method of funding the massification of the sector is having profound impacts on the human geography of those places – and is forcing students into both direct and indirect bidding wars over the bed spaces that are around, and putting intolerable pressure on the budgets of, and therefore the student experience of, both home and international students on modest incomes.

Expansion might mean that the numbers on the university’s Excel sheet add up, but without the infrastructure, the numbers on students’ budget calculators don’t.

We’ve been here before – but a proper debate about whether we want the lines on the graphs to continue in the direction that they are moving is long overdue. Compartmentalising and silo-ing the issues happens everywhere – in central government, local government and university committees – but it really needs to stop.

Those that make arguments about fees and funding, international students or the maintenance of opportunity – without referencing what different policy options might do to places, housing and resultant quality and equality of opportunity – are only telling us and the communities we inhabit half of the story.

Assuming that this analysis is using the Term Time Accommodation data returned in HESA then think it needs to be treated with caution. There are no hard and fast rules as to what point in the year this refers to. Usually it is collected at point of enrolment but I know some institutions take a different point in the year and there may be discrepancies between the Term Time Accommodation codes and the Term Time Post Codes returned. The categories are also often misunderstood by students.

For at least one university the category of “Private halls” also suddenly appears out of nowhere in the last year of data. This must be an administrative issue, perhaps with the list of options in the drop-down menu presented to students at that university having been belatedly expanded to recognise reality.

“But it is also almost certainly true, right across large numbers of major university towns and cities, that this method of funding the massification of the sector is having profound impacts on the human geography of those places – and is forcing students into both direct and indirect bidding wars over the bed spaces that are around, and putting intolerable pressure on the budgets of, and therefore the student experience of, both home and international students on modest incomes.” All this talk is about students, but nothing about ‘locals’, my son and his friends upon finishing University (in a different… Read more »