Post-qualification admissions have been shelved for now and, to be honest, I don’t mind.

It’s not that I don’t care about the admissions process, it’s just that I wasn’t persuaded by the arguments that it would lead to improvements for all the stakeholders, in particular applicants.

But I am glad that the consultation took place if it has created enthusiasm for looking further at admissions processes. Especially if we can properly explore the relationship between UCAS entry tariff offers and the tariffs achieved by those subsequently enrolled on courses.

I have been thinking about this relationship for quite some time now – whenever I heard a news report describing the stresses that students feel to achieve the grades needed to secure a university place, or when I listen to the debate around inflated predicted grades. So I decided to take a closer look, using publicly available data sets to estimate the proportion of students enrolling on courses without meeting their offer.

The data

I used data from three sources:

- Discover Uni – provides rolling 3-year data (currently 2017-2019) on actual UCAS tariffs achieved by new entrants by course, institution and nature of entry qualification (Level 3, foundation degree etc);

- Institutional course webpages – provide data on standard/contextual minimum UCAS tariff offers;

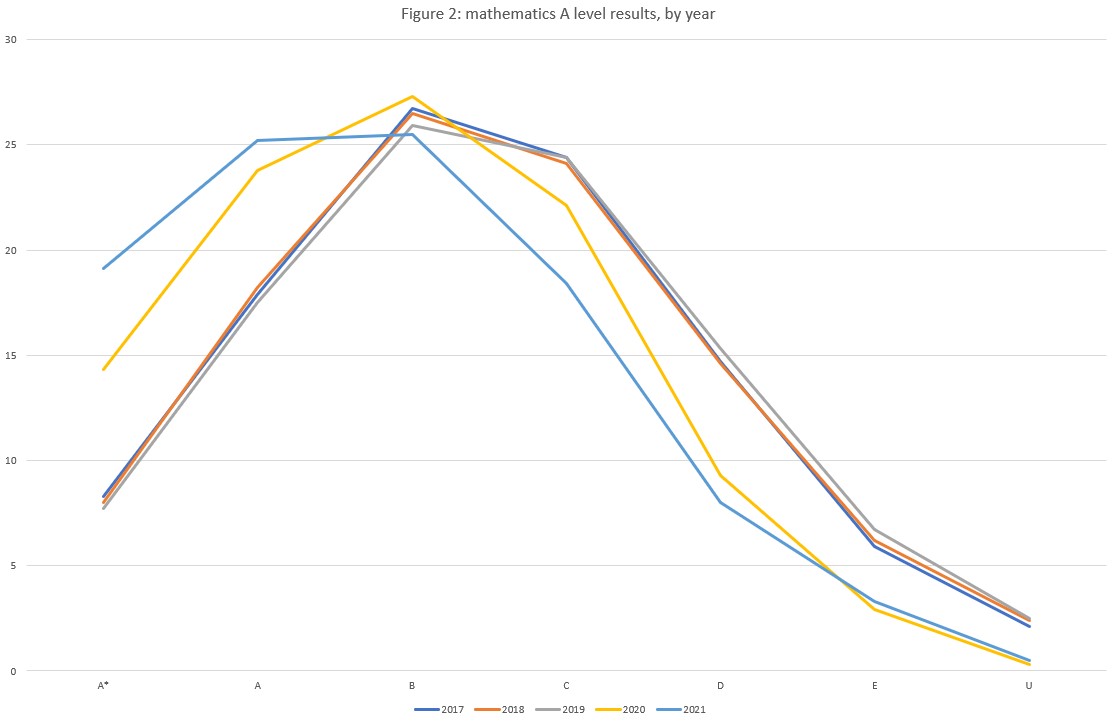

- Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ) – provides historical data on A level grade distributions by subject.

Applicants are certainly encouraged to look at the first two of these sources; I simply used JCQ data to estimate the impact of covid-related grade inflation at A level on my analysis. I wanted my analysis to mimic the experience of an applicant and so I decided to focus on a single degree course. Having worked in a Mathematics department for almost 25 years, I chose a course most familiar to me, BSc Mathematics.

Having explored the data for a while, I restricted my analysis to the 59 institutions at which at least 50 per cent of students were admitted historically via Level 3 qualifications. In 2022, there is a good range of standard offers for these courses. All courses require A level mathematics and almost half (29/59 = 49 per cent) require at least one grade A (UCAS tariff at least 128). Contextual offers, for students satisfying widening access and participation criteria, are explicitly given for 18 (31 per cent) of these courses, typically involving a reduction of 8 – 16 tariff points (1 – 2 A level grades).

Comparison of current to historical entry requirements was possible for 49 institutions from my sample. Of these, 29 (59.2 per cent) had made no material change to their standard offer in 2022, 10 HEIs (20.4 per cent) had increased their UCAS tariff and 10 HEIs (20.4 per cent) had lowered their UCAS tariff. Only one institution made a change greater than one A level grade (8 UCAS points).

Of course, Covid-related A level grade inflation is a complication when trying to use historical data as a basis for prediction in 2022 but as we see the increase in students achieving the top two grades (A* and A) in mathematics over the past 2 years is significantly less than across all subjects. This means that a student applying for BSc mathematics in 2022 has proportionately less Covid-related A level grade inflation.

The bottom line

Even with the most generous interpretation of entry requirements, my analysis suggests that between 2017-2019 only half of the institutions had at least 75 per cent of their student entry meeting the minimum requirement. And between 20 and 25 per cent of institutions had a student intake where less than half of the entry cohort had achieved the minimum entry tariff.

Anticipated grade inflation in 2022 Level 3 qualifications may lessen the number of students failing to achieve their offer this year whilst securing a place. But this will be a temporary fix whilst the staged return to pre-Covid grade distributions happens.

Why worry?

If the mismatch between offer and actual entry tariff allows students who miss their offer to enrol on their preferred degree course, why should we worry? The answer seems clear – because it puts undue stress on the student who accepts a conditional offer at the limit of their aspirational target when a slightly lower offer (1-2 A level grades) would have provided a safer target – and would still secure a place.

But the effect is felt far beyond the applicant stage. For those students admitted onto courses having missed their offer, their academic confidence can be damaged from the outset. They may be less inclined to build academic relationships with their peers thinking they won’t be good enough to make useful contributions and if they are offered additional transitional support that can reinforce their sense of failure before they even get going.

Am I just writing about something that is special to maths degrees? I don’t think so. This mismatch may not arise for all degree courses but speaking with A level students shortly after results day over several years, it is certainly true that many other disciplines have a similar track record.

And so?

I’d like to see the sector make some changes.

In the short-term we could agree to publish the percentage of current Year 1 students still enrolled at the end of the first term/semester that met their personal entry requirement together with the median actual UCAS tariff of students currently enrolled across all year groups (typically an average over 3-4 years).

And once we’ve got used to that, maybe we could use those metrics as a basis for UCAS entry tariffs? It seems like a simple solution to a potentially complex problem. But then, I am very fond of Occam’s Razor – so just maybe a simple solution might be a good solution.

What would be interesting (and I suspect difficult to map) is the relation between universities where less than half make their offer and Universities where you have a significant number of students (1/5 or 1/4) drop out in the first year.

I wonder once PROCEED takes hold and the govt starts defunding such courses if we see changes to this tariff. At the moment ‘recruiting’ Universities just pile them in and worry about if they will do well later.

UCAS have started to provide schools historic entry qual data by subject for all UK unis directly so they can better advise their pupils. Not aware of how used this is yet though. Some schools will be better set up to use this data than others I suspect.

UCAS offers are not the same as minimum entry requirements though. It’s a supply and demand system. Unless universities set offers slightly higher than needed they would end up admitting too many students.

“Unless universities set offers slightly higher than needed they would end up admitting too many students.”

That might apply at the top of the table but at the bottom where Universities are ‘recruiting’ rather than ‘selecting’ that is not a major issue especially after the last two years of the RG hoovering up student.

Many VCs at the bottom would love to have a “too many students” problem!

There maybe an error in the analysis here, what is called the minimum entry tariff is often just a symbolic representation of market position or market aspiration. It has relatively little to do with the minimum required to do the course. High demand courses often have the highest minimum tariff and this often gets higher if demand increases and conversely falls if demand weakens.

Thank you everyone for your comments. The premise of the analysis was to explore the information available to applicants. It is clear from that data that the minimum entry tariff does not correspond to the minimum required to do the course. And I guess that is my point – I think it would be beneficial to all, and in particular to students pre- and post- entry if the offers were more aligned to actual tariff entries. I’d be interested in any thoughts on my suggested solutions in which I tried to align what actually seems to happen with UCAS offer… Read more »