With the possibility that the UK may leave the EU via a “no deal” or, perhaps, a “bad” deal, we have to consider what this might mean for UK higher education.

Brexit will likely have widespread ramifications — not only in terms of our relationship with the EU as a funder for research and as a talent pool of students and staff, but also in terms of the UK’s widening participation agenda and the desire to assist those from those in society who are at a disadvantage.

There has been an impressive recovery since the 2008 financial crisis. In October 2018, the UK witnessed a dramatic drop in youth unemployment (persons aged 16 – 24) from its high of 22.3 percent in 2011 to 11.5 percent. A higher proportion of 18-year-olds are now attending university (53.52 percent of all applicants in 2018 compared to 49.8 percent in 2015). This has been driven, in large part, by a significant increase in the attendance of students from state-funded schools and colleges, as opposed to those from private-funded schools. Between 2013/14 to 2017/18, for example, private-funded school growth in first-degree applicants was 4 percent compared to 9.7 percent for state-funded applicants specifically.

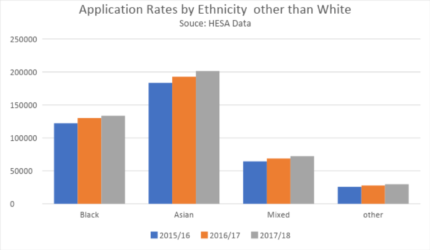

In addition, there has been a rise in participation among who students who are members of ethnic minorities. Likewise, there has been an increase in those students classified as coming from the most disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds within society. In England, application rates for low-participation areas increased to 22.6 percent.

Moreover, according to the Higher Education Statistics Agency’s Destination of Leavers from Higher Education (DLHE) survey, the 2016/17 percentage of leavers unemployed has stabilised at 5 percent of those surveyed with 15 percent in further study, which is at a five-year high.

Despite the above gains, past experience should caution us to be wary about whether these gains can be maintained. Economic uncertainty weighs heaviest on those who are most vulnerable in society. This is because those university students that come from lower-income backgrounds are often the beneficiaries of socioeconomic factors that advantage wealthier students first. There are many reasons why this is the case.

Lack of social capital

First, students from disadvantaged backgrounds often lack the social capital to ensure their success in the labour market, particularly during times where employers may become more selective in their hiring. Rather than cast a wide net, these employers may resort to “implicit” mechanisms for recruiting due to the greater supply of potential employees they will have to filter through.

Second, there is a significant “wealth effect” when the economy slows. Those within society who are wealthier and possess greater assets can tap into their holdings to sustain themselves at a higher income level over a long period of time in a down market. This affluence can allow graduates from wealthier households to wait longer before taking employment, which enables them to capitalise on specific labour market opportunities that will lead to career progression. Individuals from lower-income backgrounds, however, must often compromise on which employment opportunities they accept. These compromised choices often have lifetime income effects — students from low-income backgrounds will earn substantially less than they would have had they been able to wait for a more lucrative opportunity.

Also, as was demonstrated during the Brexit referendum, younger persons who are most in need of a greater range of economic opportunities will immediately lose out due to the UK’s departure from the EU, whereas older persons who have established their careers and accumulated assets are less likely to be impacted by economic uncertainty in the short term.

Thus, UK higher education must not only concern itself with how it will mitigate the impact of Brexit on research and EU staff and students, but it must also be careful not to overlook the impact it will have on vulnerable students here in the UK. Universities must consider how they can protect the gains of the past decade and how they can continue to provide a bridge to opportunity for those promising students who are among the first generation in their families to attend university.

A warning

The United States should serve as a warning. In the wake of the global financial crisis, the most severe impact was on low-income Americans, especially Black and Latino Americans. Studies demonstrate, for example, that by 2031 the overall wealth of Black Americans will be 40 percent lower than if the recession had not occurred. The loss in real wealth was matched by the decline in employment and earnings — and this is likely to lead to the perpetuation of intergenerational poverty because one generation’s wealth often determines the wealth of subsequent generations.

There are indicators that the UK has already absorbed an economic slowdown — in just this past quarter, the Bank of England re-forecasted a drop in GDP from 1.7 percent to 1.2 percent for 2019. Indeed, the Bank has warned that a “no deal” Brexit could be worse for the UK than the effects of the 2008 global financial crisis. There are also reports that many large private employers are pulling back on their graduate schemes. And the housing market is jittery. In isolation, these events may not seem significant, but taken together and on balance, they may foreshadow that worse is yet to come.

UK higher education must consider what the impact of Brexit and a subsequent economic slowdown will be on our WP students, and try to devise strategies to protect vulnerable students and ensure that recent gains do not slip away.

Firstly, we must recognise this risk within our institutions and communities due to potential negative fall-out from Brexit. Secondly, we must look at the reasons that economic downturns disproportionately impact low-income students and begin to prepare mitigation plans to shore up this expanding demographic. These plans must include engagement with employers, policymakers and low-income students on strategies of not only securing a job in a down market, but one that creates income momentum for life. If institutions to not begin addressing this challenge now as part of their Brexit planning, the widening participation agenda may end in failure for many of our first-generation students.

Well, the first thing to point out is that this post is hypothetical in that it is based on some major assumptions. The UK has to leave the EU without a deal and the growth rate after Brexit has to turn out slightly slower than would otherwise be the case. I just checked BBC news and the assumption of leaving without a deal looks a lot less likely than leaving with one or not leaving (just telling you…). The second thing is that EVEN IF you do accept these premises, the demand for full time higher education in the past… Read more »