The general public would be forgiven if they thought a student’s degree mark and classification was based on an average of all their marks in the courses they took while doing their degree, and that the procedure for calculating this average was similar across all UK universities.

They might also assume that two students who were both awarded first class honours might have achieved similar marks (albeit in different subjects).

However, these reasonable assumptions would be incorrect.

The way UK universities calculate a student’s degree mark varies from university to university, where differences arise in:

- The number of years used in the calculation

- The weightings given to those years (or differential weighting)

- Whether lower marks are ignored (or discounted)

This diversity means that:

- The same set of marks would receive a different classification depending on which university the student attended (or even which degree programme they were on within a given university).

- Students with inconsistent marks are advantaged while those with consistent mark are not.

- We cannot make any meaningful comparisons between universities based on their student’s achievement – which has implications for our understanding of attainment gaps.

Whether different degree marks from different algorithms matters depends on the full extent of this diversity in degree algorithms.

Measuring the variation in UK degree algorithms

In an effort to gauge the range of algorithms used across the sector, in October 2017 Universities UK and GuildHE published survey data from 113 UK universities. However, the picture from the survey results was perhaps a bit piecemeal- in that it identified a range of different weightings applied to years 1, 2 and 3, but which did not include any discounting. The extent of discounting was discussed separately (on page 37 of the report), which suggested that around 36 UK universities used discounting in their algorithms. Again, it was not clear whether these 36 universities also used differential weighting.

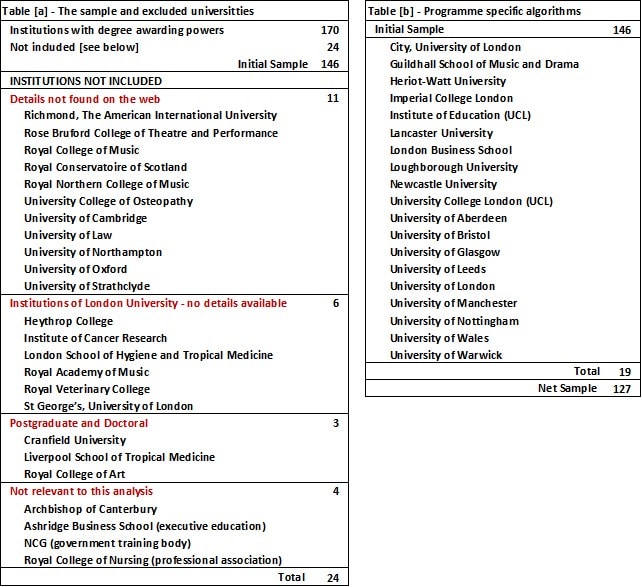

In January 2020, I reviewed the academic regulations for all institutions with degree awarding powers. The method employed was simple (if not tedious) and involved looking at all the academic regulations posted on the institutions’ web sites. Their algorithms were then classified according to the number of years used and whether discounting and differential weighting were applied. The review revealed a surprising diversity in UK degree algorithms:

- Of the 170 institutions with degree awarding powers 24 institutions were excluded because the details were not found on the web, they did not offer undergraduate courses or, were not relevant to undergraduate provision .

- A further 19 institutions were found to be using degree specific algorithms that is to say; there is no university wide algorithm. These universities have general regulations that apply to all programmes, e.g. they might state that the final degree is based on year 2 and 3 (levels 5 and 6 FHEQ) and they lists a range of prescribed weightings. For example, at Newcastle the degree is calculated using all year 2 and 3 marks (i.e. 240 credits), but programmes have a choice of weightings: 50:50, 33:67, 25:75 year 2 and 3 respectively.

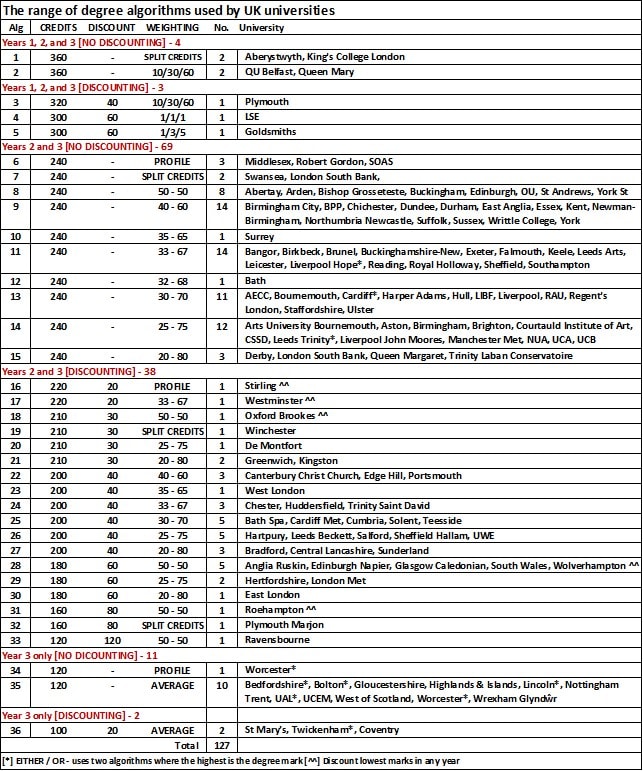

- Of the remaining 127 universities only 7 used all years of study (years 1, 2, and 3), 107 based the degree mark on years 2 and 3, and 13 use only the final year (year 3).

- Six universities use split-credits; here the marks within a year are batched and weighted differently. For example, at Swansea, the best 80 credits at year 3 are given a weighting of 3, the remaining 40 credits at year 3 and the best marks in 40 credits in year 2 are given a weighting of 2, and the remaining year 2 marks a weighting of 1.

- Five universities use profiling where the preponderance principle is applied to determine the student’s classification (as opposed to degree mark). The process begins by ranking the student’s marks and then looks at the proportion of marks at or above a given mark. For example, a student might be awarded a 1st where they have attained 90 credits at 70% or higher and 30 credits at 60% or higher – this might apply to all year 2 and 3 marks, or part of year 2 and all of year 3.

- Nine universities use two different algorithms (Either / Or) where the final Classification is determined by the algorithm with the higher average mark. Generally, the first algorithm uses a broader range of marks (e.g. all credits from years 2 and 3), where the second algorithm is narrower and has a higher proportion of year 3 marks, or in the case of 6 institutions, uses only year 3 marks (which is more forgiving to those students with better marks in year 3).

- Of the remaining 116 universities, 76 use differential weighting and, 40 use discounting combined with differential weighting.

Table 1

The full range of algorithms is shown in Table 2. Significantly, no university takes the straight average of all years. The closest to this overall average is the LSE algorithm, (algorithm 4) but which ignores 60 credits with the lowest marks in year 1.

Table 2 also shows that there is further variety within a given algorithm. For example, some universities discount the lowest marks in any year (see marker ^^ in table 2) – which makes the algorithm almost unique to the student. Likewise, in algorithm 26 two of these universities (UWE and Hartpury) allow the unused credit from year 3 to be “counted towards the second 100 credit set of best marks” (i.e. year 2). That is to say and, depending on the student’s marks, up to 40 credits in year 2 could be discounted.

This review found yet more variation in terms of the degree classification boundary marks. When it comes to 1st the range stretches from 68% (Bradford University) to 70%, with 69.5% being very common. Similarly, the range of marks that would attract a borderline consideration can range from 2.5 to 1.5 percentage points below a given boundary mark.

Table 2

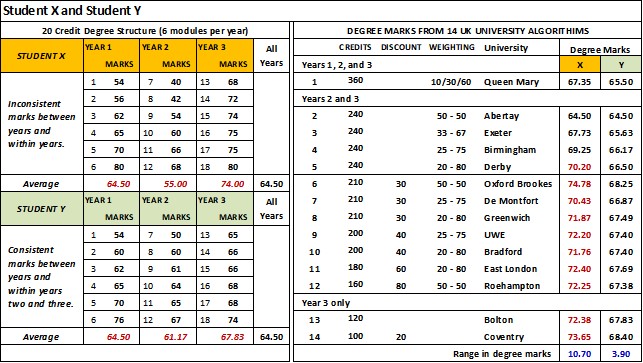

Why it matters – student attainment comparison

We can illustrate the implications of this diversity in degree algorithms has on students’ attainment using a worked example. Table 3 lists the module marks for two students X and Y on a degree programme using 20 credit modules. Student X’s marks could be described as inconsistent – with big differences between the yearly averages, whereas Student Y’s yearly marks are more consistent. It is notable however that in this example, both students have the same year 1 average (64.5 per cent), the same average for years 2 and 3 combined (64.5 % – see the mark for Abertay) and the same average across all years again 64.5 per cent.

The table shows how 14 different algorithms use these module marks to derive the students’ degree marks and demonstrates that when combined differential weighting, discounting, and different counting years can have a significant effect on the student’s final degree mark and classification. To reiterate, these differences mean that;

(a) The same set of marks would receive a different classification depending on which university the student attended (see Student X).

(b) Students with inconsistent marks are advantaged while those with consistent mark are not (compare Student Y to Student X).

For Student X the range in their degree marks is 10.7 percentage points, they would receive a 1st (76.65 per cent) had they gone to Coventry, but a 2:1 (64.50 per cent) had they studied at Abertay. We might also wonder whether Student X’s marks reflect what those outside the sector (e.g. employers, parents, and media) might commonly think of as the likely marks that make up a 1st.

Conversely, the range in degree marks for Student Y is only 3.9 percentage points and they would have received a 2:1 no matter what university they attended (see appendix – table D). However, had Student Y’s average marks for years 2 and 3 been higher e.g. 68 per cent, the spread of degree marks (3.9 percentage points) might have resulted in some algorithms returning a degree mark above 70 per cent.

Table 3

The unfairness of the current arrangements speaks for itself. This inequity probably drives QAA recommendations that institutions reduce the variation within the institution (although the QAA is less vocal about the variation between institutions). Similarly, the complexity of some of these algorithms makes it challenging for students to set target marks or to gauge how they are doing in their studies.

There is however one major issue that has not been considered. Namely, the impact this variety in algorithms (or indeed any widespread changes in them) has on any comparative analysis involving degree outcomes, principally, attainment gaps based on the proportion of good honours (issue (c) above).

Why it matters – comparisons between universities

Under the current system, the traditional classifications are not standard measures of attainment. If asked “when is a First a First?” we can only say … “Well it depends on which university the student went to.” Furthermore, as it currently stands where some student’s achievements can only be described as ‘algorithm assisted’, we are not comparing like with like. We can demonstrate the problem using two media based league tables.

In the Complete University Guide 2020 league table, Coventry’s proportion of good honours is 76.1 per cent, which compares to 75.7 per cent for Brunel. Yet the two algorithms are very different (algorithm 36 and 11 respectively in see table 1), such that the Brunel’s achievement says something different about its staff and students – but which, in the absence of any unadulterated averages, is near impossible to quantify.

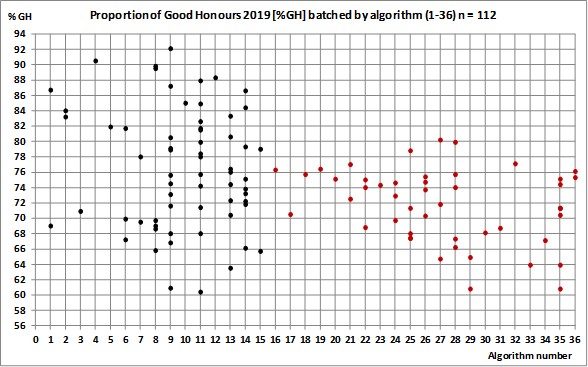

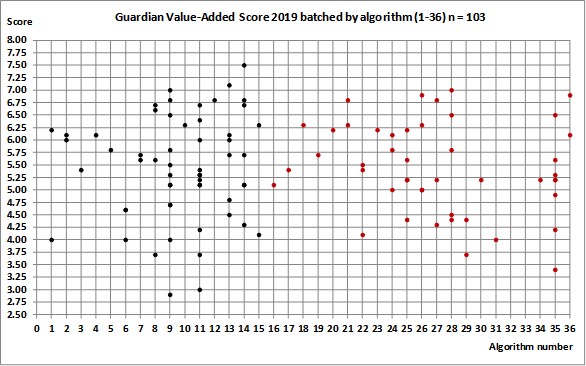

As figure 1 shows, it is only with some understanding of the range in degree algorithms that we could start to identify meaningful comparisons but only within a particular algorithm.

More generally, figure 1 suggests that discounting (algorithms 16 onwards) is perhaps concealing the true extent of student achievement (or lack thereof) in a large number of universities. However, this conclusion rests on the assumption that generally, the discounted marks are lower than the counting credits, and that year two marks are also lower than the final year marks.

Figure 1

Likewise, the Guardian League table and it’s value added score which “… compares students’ degree results with their entry qualifications, to show how effectively they are taught. It is given as a rating out of 10.”

In the 2019 table, Sheffield (algorithm 11) and Nottingham Trent (algorithm 35) both have a value added score of 5.1, yet the algorithms are very different, such that we cannot reasonably make a comparisons between these two algorithms.

Figure 2

At a national/policy level this variety in algorithms also makes it difficult formulate informed policy. A case in point would be accurate measurement of attainment gaps based on the proportion of good honours across different groups of students. Currently, we cannot know if these gaps are being reduced or increased because of differences (or changes) in university degree algorithms.

A proposal

The problem defines the solution: we need a standard measure of attainment. If higher education policy is to be better informed there has to be a “levelling up” in the measurement of student attainment.

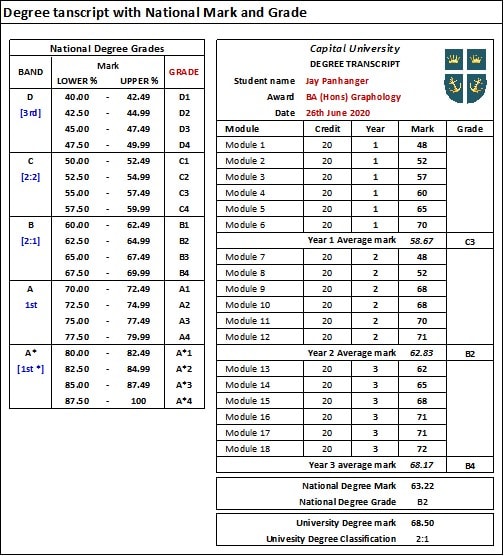

To this end, I would propose a national degree mark and grade based on the students’ average marks across all years. This mark and the yearly averages would be recorded in the student’s transcript alongside the university’s mark and classification (see table 4). These marks would also be supplied to HESA and used in its annual report on student attainment.

Table 4

Importantly, universities would not have to change their current algorithms nor their academic regulations (their autonomy remains intact). That is to say, nothing is ‘being changed’, it’s simply ‘being added to’. Indeed, as an unadulterated average, this national degree mark would not require any regulations – it is what it is.

For universities, this proposal is also cheap to implement, they have the data already, it only requires changes to the coding of existing data bases to collate, record and publish this data. In all respects, this proposal is a simple bureaucratic change in the reporting of student achievement as such it does not really require any extended period of consultation with universities.

The data underlying this analysis is available as an excel file.

Having done similar analysis (more granular, with a smaller set of institutions) I would agree that the huge variation, and the extent to which that variation is defensible, is genuinely interesting. However, I’m not sure that complete comparability is achievable or desirable (teaching and assessment practice, content and the pass mark/marking criteria all have a significant impact, and are not consistent), even if this does make (more of a) nonsense of the OfS’ treatment of statistics. Nor am I certain that the simple, elegant solution posed entirely solves the problem. Others matters to consider are: the extent to which modules… Read more »

As the article demonstrates there is a lot of variation in the degree algorithms used across the sector and in some cases within an institution, there is definitely a case for increased simplicity and and transparency for students however the analysis does not account for the differences in teaching, learning and assessment across institutions for which algorithms often look to account for. Even something as simple as module size and the assessment strategies of those modules can impact a students performance with algorithms being a part of overall academic regulations which apply to students. This is before we start to… Read more »

Hello Andy – you are completely right about the wide variety in the reassessment of modules, capping of marks, condonement and compensation and much more besides (e.g. in particular the rules for ‘uplifts’). Indeed, to record and classify this variety would have taken another two months of work. Likewise, I agree that as long as institutions control their curriculum there will be variation – which is only right and proper. What I would like to stress is that my proposal is not asking for any of this to be changed or harmonised (but it can be if universities so wish).… Read more »

Hello Phil – as with Andy’s comments above, I agree there is variation in teaching and assessments across institutions, which is a good thing. You also raise good point about module sizes – my own simulations show this can be very relevant where discounting is used. I would however quibble about whether all algorithms are configured to account for these differences – as most regulations do not offer any rationale (to students or staff) for ignoring year 1, discounting and differential weighting. Which leaves us asking why are we doing this? In the meantime, I think we can overlook how… Read more »

Thanks David, I agree with what you’ve said, and didn’t mean to imply you were implying we needed greater standardisation. Your proposal, as you said, is about an alternative measure which would avoid the need for standardisation. My point was more that a(n admittedly smaller) number of the wider factors which are not part of but which directly affect a student’s final classification, will also affect the way individual module marks are determined, and also therefore your affect your simple alternative average – permitting reassessment even if a module is passed and/or not capping modules and/or permitting credits at lower/higher… Read more »

Hello again Andy If I have read you comment correctly you are making the following points: (i) that the regulations and procedures around individual module marks can have a significant impact on a student’s classification. Particularly in the case of marginal degree marks which are uplifted using the preponderance principle (where there could be pressure on staff to avoid awarding marks close to a boundary e.g. 59% or 69%), or more generally whether the mark is capped at 40% etc. This being so then (ii) an overall average yearly mark will be affected in a similar manner. This then means… Read more »

Interesting article with some valuable analysis. However, we need to recognise the benefits to variation to appreciate the full complexity of the situation. Three examples: i) in a medical or other professional course, you could attain highly on average but, if you’re failing key modules that determine safety of practice, this would not be considered good performance. ii) in arts degrees it is understood that you advance your practice year on year, building to a final “piece.” Surely it makes more sense for the weighting to be shifted to the final year in this case? iii) having a poor performing… Read more »

Hi David – Yes, that is broadly what I’m saying. But i was actually surprised at how much variation module-level rules could have on your proposal. To give two examples which would impact at different levels (again, this is from a much smaller sample than you used for your study of algorithms themselves): At lower levels of study: take two, large pre-92s in the same region. Both permit resits at Levels 4 and 5. At one all resits are uncapped, with the resit mark replacing the original failing mark; at the other, all resits are capped, and capped at 30… Read more »

Thanks Leigh You are (I think) questioning the comparability of the national degree mark and grade, or more generally the whole notion as to whether comparability across UK degrees is desirable (which seems to be a common thread in the comments made so far). So to be clear: I accept (unreservedly) that there is a difference between degree programmes, furthermore, I would not support any sort of ‘national curriculum’ being applied to the UK Higher Education sector (professional accreditation aside – see below). This is the old debate about whether a degree in History from Oxford is ‘comparable’ to one… Read more »

Thanks Leigh You are (I think) questioning the comparability of the national degree mark and grade, or more generally the whole notion as to whether comparability across UK degrees is desirable (which seems to be a common thread in the comments made so far). So to be clear: I accept (unreservedly) that there is a difference between degree programmes, furthermore, I would not support any sort of ‘national curriculum’ being applied to the UK Higher Education sector (professional accreditation aside – see below). This is the old debate about whether a degree in History from Oxford is ‘comparable’ to one… Read more »

Again Andy you are right! Currently, the variation in module regulations mean that the national degree mark (and grade) will be different (at least to start with). However, what’s missing from your two undergraduate examples is the rationale behind each regulation – allowing an uncapped mark or, capping the resit mark at 30%. I expect in the latter the university uses discounting and knows this procedure will ignore the 30% mark. I would however advise this university to revisit this regulation: if 30% is a fail, then the learning outcomes of that module have not been met – which could… Read more »

Fascinating and thought provoking discussion and opens up a plethora of questions. Would be very interesting to see comparison betweek UK algorithms and those used in other countries.

Again I am no expert, but it looks like the rest of the world uses variations of the Grade Point Average – particularly in the USA and Asia. Europe also has a unified system – European Credit Transfer system (ECTS), where the general belief is that “principles of justice and fairness, deemed central to academic freedom, are best upheld by the use of a unified grading system at national and European levels” (page 1). (see: Karran, T. (2005), Pan-European Grading Scales: Lessons from National Systems and the ECTS Higher Education in Europe, Vol. 30, No. 1, April 2005. Higher Education… Read more »

Ever since I came across “Degrees of freedom: An analysis of degree classification regulations” (Curran & Volpe, 2003) I’d hoped to find five minutes (!) to repeat a similar exercise so am very pleased you’ve managed to do something like it (thank you!). I think the Degree Outcomes Statements will prove interesting in this regard – we will be addressing your queries (i.e. I would however quibble about whether all algorithms are configured to account for these differences – as most regulations do not offer any rationale (to students or staff) for ignoring year 1, discounting and differential weighting) in… Read more »

I look forward to your analysis (but I confess I do not know what a ‘DOS’ is). I do know that of all the regulations I looked at the rationale for discounting and differential weighting was ‘thin on the ground’. Some regulations talked of ‘exit velocity’ (as a justification of a higher weighting on the final year) but none I read (or at least comprehended) explained discounting (including the omission of year one marks).

Hi again Davd. Interestingly, no, neither HEI discounts. I suspect the pass mark is set at 30 because the HEI compensates marks of 30 (i.e. deems them to be passes, as long as they aren’t core and other criteria are met), and runs compensation before resits – the cap of 30 thereby avoids advantaging students who resit a mark of below 30 and resit over those who receive automatic compensation. In fact, the widespread use of compensation – which typically comes with a minimum threshold and other criteria, such as an average of 40 for the year, meaning narrow fails… Read more »

Hello Andy thanks for the clarifications regarding compensation and condonement (a minefield in its own right). I unreservedly accept that while there is variation in the regulations covering modules this suggested additional measure will not offer perfect ‘comparability’ (and can’t). However, we need to remind ourselves where the current variety in regulations manifests itself: (i) at module level when determining marks and passes (ii) at degree level when determining the overall classification The proposed national degree mark and grade is designed to tackle the issues and implications that arise in (ii), which are bigger in magnitude than the issues that… Read more »

Hello Andy thanks for the clarifications regarding compensation and condonement (a minefield in its own right). I unreservedly accept that while there is variation in the regulations covering modules this suggested additional measure will not offer perfect ‘comparability’ (and can’t). However, we need to remind ourselves where the current variety in regulations manifests itself: (i) at module level when determining marks and passes (ii) at degree level when determining the overall classification The proposed national degree mark and grade is designed to tackle the issues and implications that arise in (ii), which are bigger in magnitude than the issues that… Read more »

Hello Andy thanks for the clarifications regarding compensation and condonement (a minefield in its own right). I unreservedly accept that while there is variation in the regulations covering modules this suggested additional measure will not offer perfect ‘comparability’ (and can’t). However, we need to remind ourselves where the current variety in regulations manifests itself: (i) at module level when determining marks and passes (ii) at degree level when determining the overall classification The proposed national degree mark and grade is designed to tackle the issues and implications that arise in (ii), which are bigger in magnitude than the issues that… Read more »

I would expect most people would want a degree to show how much someone has learnt by the end of their degree, not how much they knew in the first year of the degree. Shouldn’t it be possible for someone to start out with lower skills and to catch up with their peers by the end of their degree?

This suggests to me that the final year should be weighted much higher and the first year discounted completely.

Hello Andy thanks for the clarifications regarding compensation and condonement (a minefield in its own right). I unreservedly accept that while there is variation in the regulations covering modules this suggested additional measure will not offer perfect ‘comparability’ (and can’t). However, we need to remind ourselves where the current variety in regulations manifests itself: (i) at module level when determining marks and passes (ii) at degree level when determining the overall classification The proposed national degree mark and grade is designed to tackle the issues and implications that arise in (ii), which are bigger in magnitude than the issues that… Read more »

Hello Dave Clearly, this is a view shared by many – after all, in the sample, I looked at only 8 universities weighted second and third year equally, and only 7 include the first year. However, it’s worth remembering that the proposed national degree mark and grade (NDM+G) will not replace the algorithms currently used by UK universities. Rather it complements them and I think we will see a general improvement in the students’ academic performance. To explain: Its my experience that for students there are two aspects to learning (at university level) where the first is actually internalising that… Read more »