Elsewhere on the site, Steven Jones reports on his new research revealing the “wrong kind of compliance culture” in some university governing bodies.

The report, produced for the Council for the Defence of British Universities, is a cracking read – and in particular the testimonies from student governors on their experiences will chime hard with those gathering in London for Advance HE’s second mid-year student governors training event this week.

I’ve been helping the team at Advance HE with delivery on their programme for a long time now, and I could fill another 30 page report with some of the examples of the way in which they can tend to be “othered”, or their contributions dismissed, either by managers or other (usually lay) governors.

One of the things I do worry about, though, is the tendency for the sector to frame student, staff (and some lay) governor contributions or outlooks as not appropriate for the “proper” role of governance in a university. The standard line – “you’re here to be concerned with the university rather than as a representative” – is often laid on a bit thick and too simplistically for my liking.

If nothing else, when any governor raises something that some might regard as more operational than strategic, there’s usually a fruitful conversion waiting to be had about the underpinning policy, regulatory or cultural drivers that surround the issue.

As such I do worry that in some quarters, the CDBU report will be met with rolling eyes or promises for enhanced support or revised recruitment that causes those concerned more with (student, staff or local) community issues than they are with bricks and mortar, recruitment conversion stats or risk registers to change their ways. At best, my fear is that staff, student (and some lay) governors will be seen as the issue to be “fixed”.

More generally, as well as “getting up to speed” and knowing the lingo, I suspect the dominant development question for those influencing Board practice tends to be about how people might be caused to “lean in” to existing assumptions about what governance is, how it’s done and who does it – rather than a critical reflection on how it might be done differently.

Turn to the books

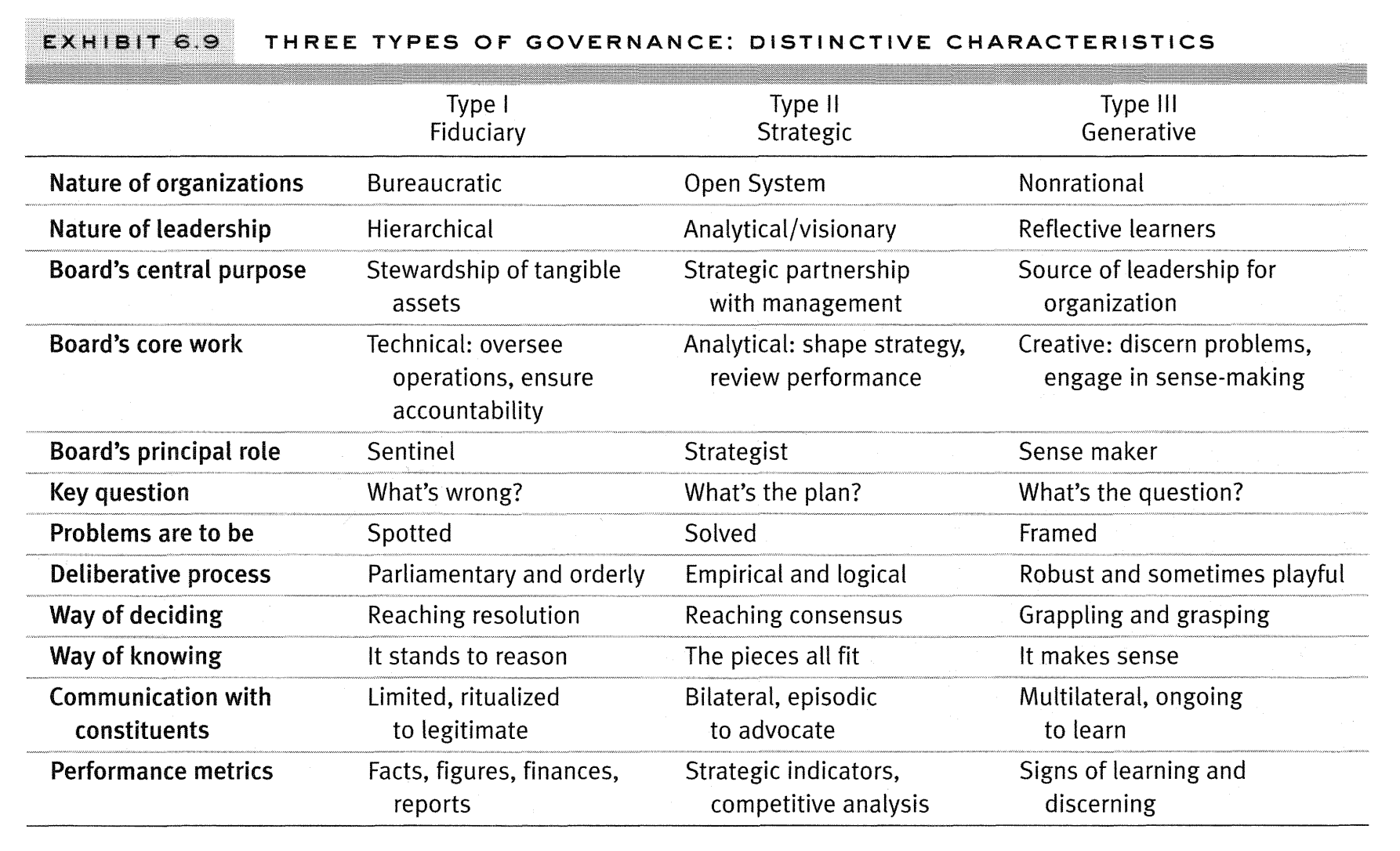

One of my favourite bits of academic work on this comes from a 2004 book called Governance as Leadership: Reframing the Work of Nonprofit Boards. Informed by theories that the authors argue have transformed the practice of organisational leadership, it takes the traditional fiduciary and strategic focus of a board and introduces a third dimension of effective trusteeship – generative governance.

In the book – an extract of which someone has posted online here – the authors describe fiduciary work focussed on the stewardship of tangible assets, ensuring financial health, and compliance with legal and ethical standards – as well as compliance with relevant laws and regulations.

We’re talking overseeing budgets, auditing, dashboards, and without it, the organisation would be “irreparably tarnished or even destroyed”. It’s the sort of stuff that I suspect dominates BoG and Council agendas.

It then describes another type – the strategic work that enables boards (and their management) undertake to set the organisation’s priorities and course, and to deploy resources accordingly.

We’re talking planning, setting organisational priorities, and making decisions about significant initiatives and policies – it’s more future-oriented than the fiduciary mode and requires a deeper understanding of the organisation’s environment, opportunities, and challenges.

Without it, governance has little power or influence, because if a board neglects strategy, the organisation could become ineffective or irrelevant. It’s the sort of thing that I suspect tends to happen more often on away days than at the main committee tables.

The authors don’t suggest that the two types can be ditched – in fact their research suggests that both sorts of activity are essential for governance to work. But what’s fascinating is that they suggest a third type of governance as essential to the success of a Board – the “generative mode”.

Often the least practised but crucial for innovative and effective governance, it involves critical thinking, questioning assumptions, and framing problems and solutions in insightful ways – and is where boards engage in sense-making, exploring root causes of issues, and developing a deeper understanding of the organisation’s purpose and potential challenges.

Ideal, in other words, for those governors whose experience is more about being a student, staff or community member of the board. It requires creativity, deep(er) engagement, and an ability to see beyond the apparent and immediate in the dashboard or the risk register.

What did he say?

If practised, it changes what governors might say, what items might be presented for discussion, how managers or other governors respond to challenge, or even how a “fiduciary” or “strategic” item might be handled.

Governors in generative mode might ask (and be encouraged to ask) probing, foundational questions that challenge assumptions and norms. Examples include: “What is our fundamental purpose?” or “How does this decision align with our core values?”. They are less demanding of a “reassuring response” from the executive team – and more about exploration.

If that all sounds a little wishy-washy, it also involves (more) scenario planning and contingency thinking – engaging in “what-if” scenarios to anticipate future challenges or opportunities and to think through potential responses. There’s almost certainly a dearth of this sort of stuff in university decision-making in general, let alone around the oak council table.

It suggests that instead of just addressing symptoms of problems, this mode delves into the root causes to find more effective, long-term solutions, and is more often vigorously critical – analysing information, not taking things at face value, and being willing to challenge prevailing wisdom, as well as being open to discussing the ethical implications of decisions, beyond legal compliance, and actively considering the views and needs of employees, beneficiaries, and the community.

And crucially, rather than setting up an opposition between student, staff and community concerns or ethical implications and “the real work of the board”, it integrates them properly into the thinking a board does:

The majority of boards work most of the time in either the fiduciary or strategic mode. These are comfortable zones for trustees. Nonetheless, many boards neither overcome the inherent challenges that Types I or II pose nor capitalise on the occasional leadership opportunities that fiduciary and strategic governance present.

As a result, some of the board’s potential to add value goes untapped, despite the trustees’ familiarity with the mode. However, there may be an even steeper price to pay if boards overlook or underperform Type III work because, unlike Types I and II where there are moments for leadership, the generative mode is about leadership. It is the most fertile soil for boards to flower as a source of leadership.

Putting it into practice

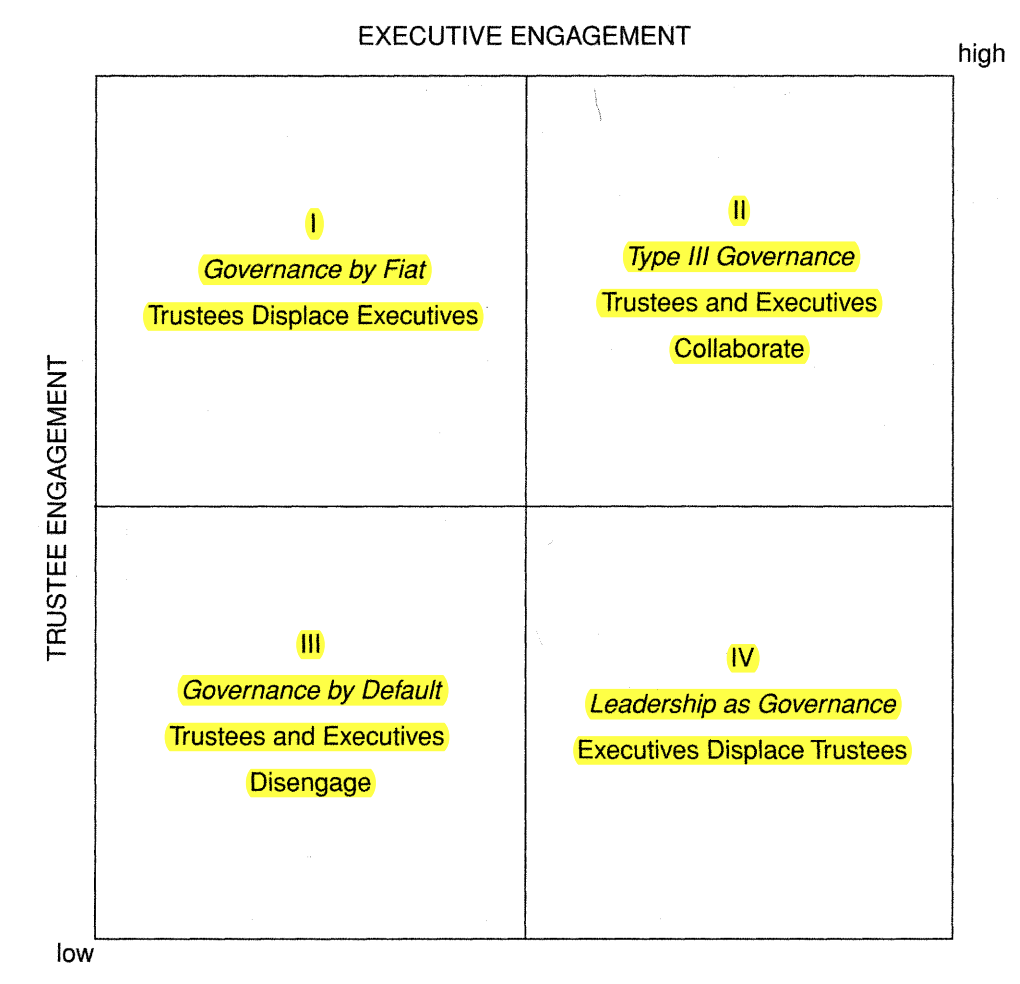

There’s compelling material in the extract on what it might all mean in practice – not least getting over the “governors meddling in management” versus “managers lead everything and perform to reassure” dichotomy that many boards (in multiple sectors that I’ve encountered) seem to wrestle with.

And the section on section on “promoting robust dialogue” is particularly helpful – noting the dangers of preferring harmony and congeniality over productivity and candour (and the way that inhibits the type of meaningful discussions necessary for addressing complex issues), it looks at exploring sensitive subjects, probing, testing, and debating propositions and maintaining civility – all while avoiding dysfunctional politeness and groupthink.

Page 61 of the extract provides some superb ways of facilitating trustee deliberations (that I’ll be recommending to SU trustee boards) that are highly participative and relatively spontaneous – and while the text notes that they may strike some governors as “parlour games”, many boards, used to more formal discussions, have used these devices fruitfully to adadpt to a different approach:

As the board becomes more experienced and comfortable with the generative mode, there will be less need for such “contrivances”, and robust discussions will occur more naturally.

As the financial “headwinds” and the regulatory compliance issues close in on the sector, there’s even more of a danger than usual that this type of governance gets shut out as being frivolous or unnecessary.

But my sense is that the hostile operating environment demands more of it – and that when combined properly with those types we’re familiar with, it’ll help universities survive and thrive, and mean the CDBU’s next report might not be so depressing to read.