Some have argued that the Home Office announcement banning international PGTs from bringing dependants into the country represents a “kneejerk reaction” to a positive response to the graduate route.

Their argument is that eventually students will leave – but that given the graduate route (offering two years of post-study work) only opened in the summer of 2021, in the meantime net migration figures will look distorted.

That sounds like a subtlety too far for Britain’s fractious immigration debate. We get net migration figures twice a year, and given the prominent role that students (and their dependants) played in numbers six months ago, if anything it’s a wonder that it’s taken the government so long to act.

Suella Braverman’s big announcement was an attempt to get ahead of the figures – we now have 2022’s numbers, alongside the quarterly numbers for visa issuance from the Home Office covering the first quarter of 2023. The question is what those figures tell us about what might happen next.

Record highs, but “not out of control”

The major national headline is that total long-term immigration was estimated at around 1.2 million in 2022, and emigration was 557,000 – which means migration continues to add to the population with net migration at 606,000. That’s lower than speculation suggested it would be – allowing PM Rishi Sunak to defend the position as follows:

Rishi Sunak tells @thismorning on net migration: “The numbers are too high, it’s as simple as that. And I want to bring them down.”

But he denies figures are “out of control”

— Lizzy Buchan (@LizzyBuchan) May 25, 2023

The ONS narrative surrounding the figures notes that the lifting of travel restrictions in 2021 saw a substantial increase in students arriving in the UK long-term in Q3 2021 after studying remotely during the pandemic, as well as referencing the attractiveness of the graduate route.

We knew a version of this bit already based on previous visa issuance figures – but here we have confirmation that since 2020, the immigration of people on study-related visas has increased by 248,000 – from 113,000 to 361,000.

But how many leave? It matters because Braverman et al have argued that “some universities” are selling economic migration rather than study – and as such you may recall her minister Robert Jenrick suggesting that one in four don’t leave a few months ago, a point he repeated in Parliament this week.

Given the increase in immigration of those on study-related visas in the last two years, ONS says we’re now seeing an increase in emigration as those students come to the end of their studies – driving an increase in total emigration from 454,000 in 2021 to 557,000 in 2022 – although getting more precise than that is tricky.

A previous ONS note from 2021 did indeed suggest that 61 per cent of non-EU students left at the end of their study visa in the academic year ending (YE) 2019, and in that case the majority of the remaining 39 per cent obtained additional visas, or received visa extensions. It’s harder to know what happened next.

Frustratingly, because of the way the data is compiled (and wider concerns over the way the immigration data is collected), the overall estimates on leaving can’t currently be combined with immigration estimates to produce a net migration estimate by visa type – because it doesn’t account for people who transition from their initial visa onto another visa type.

In other words while we know that many leave at the end of their studies, and that just over a third stay, someone who arrived to study for a year and then worked for three years would be counted out as a student – so the contribution of the work element of their stay, and their contribution to population change, would be missed.

The big issue is that as ONS notes, students’ plans may change – and this goes to the heart of why it’s so difficult to just lift students from net migration figures:

- not including students in its immigration estimates, but including those who stayed beyond their student visa in emigration estimates, as emigrating workers for example, would lead to underestimation of net migration;

- not including students who, post-study, transfer to an alternative route and subsequently stay in the UK, would lead to net migration under-estimates;

- including those who enter via non-student routes in our immigration estimates, but then excluding their emigration after a transfer to a student visa would lead to overestimation of net migration;

- not including those who we cannot identify as a student (Ukraine, BNO, EUSS, British) in the student population, leaving them in the general population, would lead to overestimation of net migration;

ONS sets out two options for quantifying students in its net migration estimates that would avoid the inaccuracies mentioned, with a view to providing a research update on the method in November 2023. But for now, we don’t really know.

Are numbers still growing?

So we can see that in time, it may well be possible to more accurately determine how long students stay for, which would help the argument about net migration.

But if numbers continue to grow at the pace that they have been, the argument will be that the impact of those leaving is lost. So are they still growing? And what’s going on with dependants?

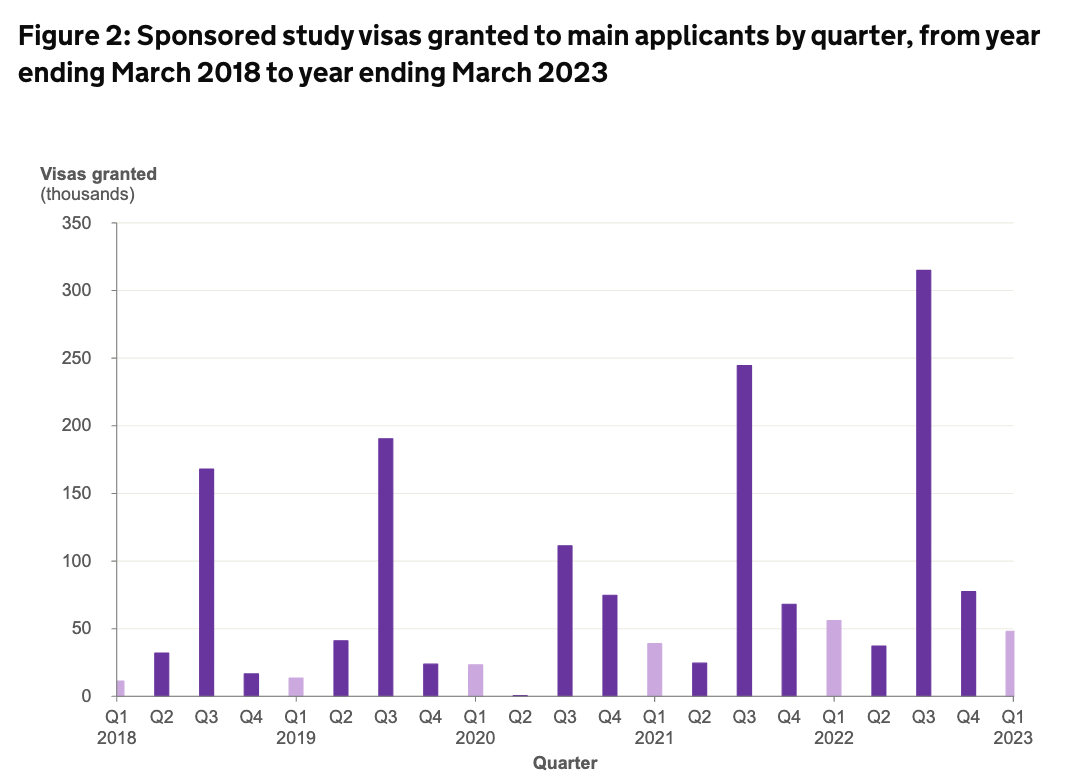

For the past two quarters we’ve seen record visa issuance for the main September and January intakes respectively. Separate to the ONS numbers, we now have the Home Office’s latest quarterly update.

Interestingly, figures for quarter 1 of 2023 actually show a decrease in main student visas issued year-on-year, from 56,027 to 48,200. Of course, both Q1 and Q2 are small beer in comparison to Q3 and Q4, but if the reduction becomes a trend there will at least be some national relief that main applicant numbers are starting to level off.

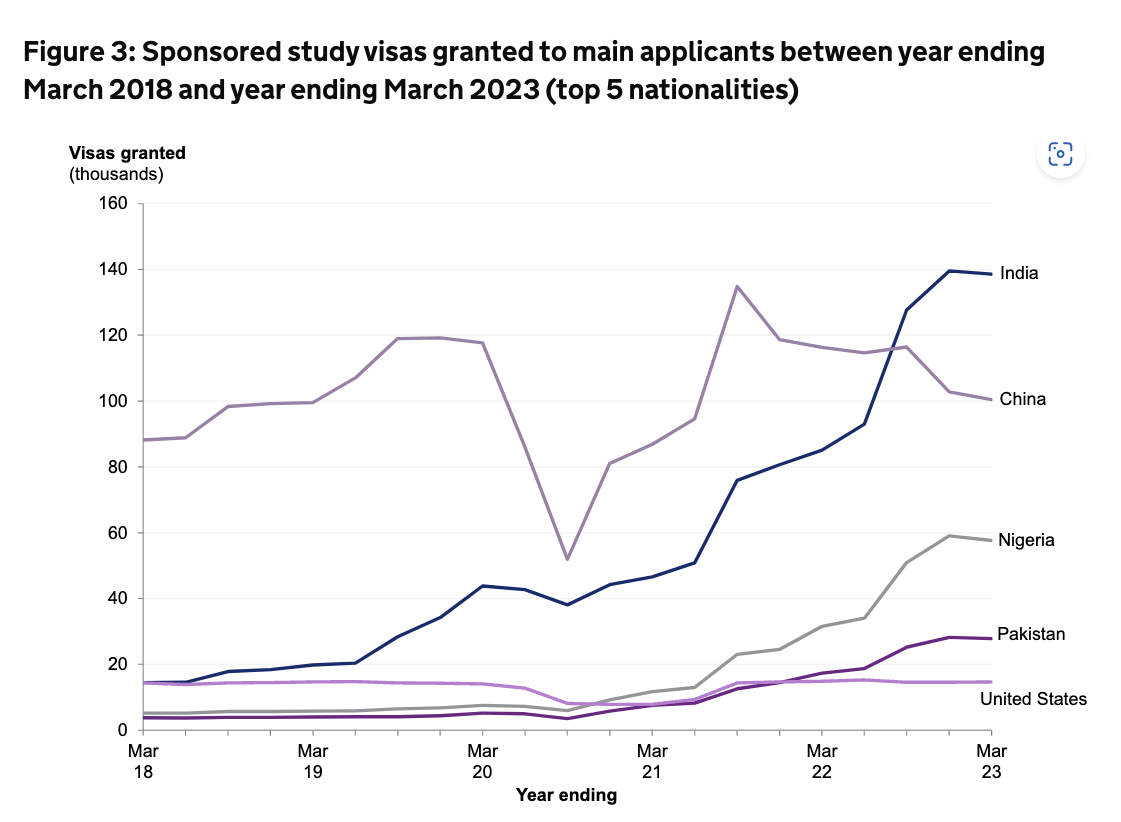

Again, the story of differences by country has been told before, with the Year to end March 2023 showing again the rise of India, Pakistan and Nigeria and the decline of China:

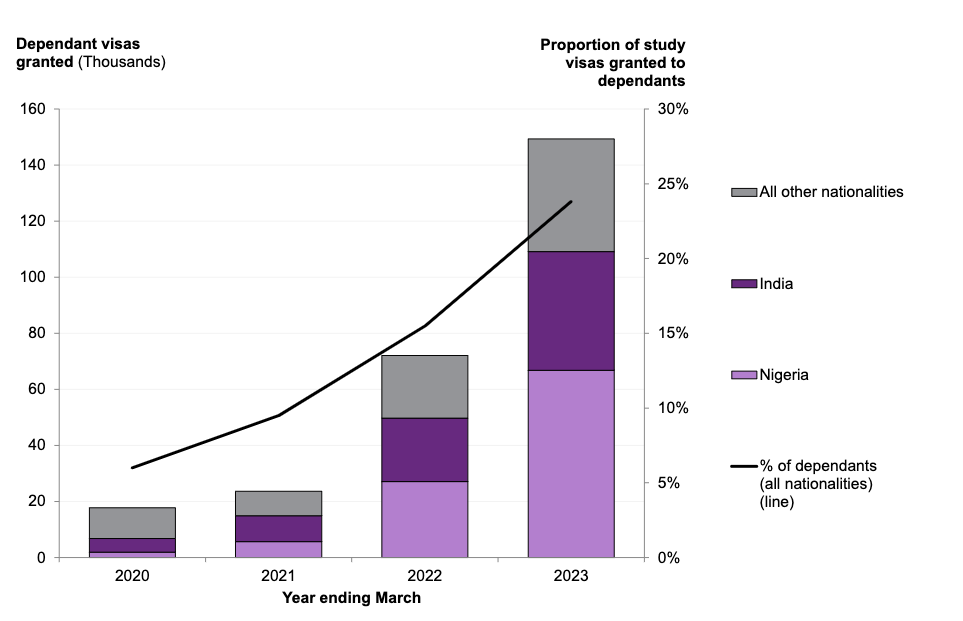

But what’s interesting is that while overall main numbers for 2023Q1 numbers are down, overall numbers are up – and that’s driven by dependants:

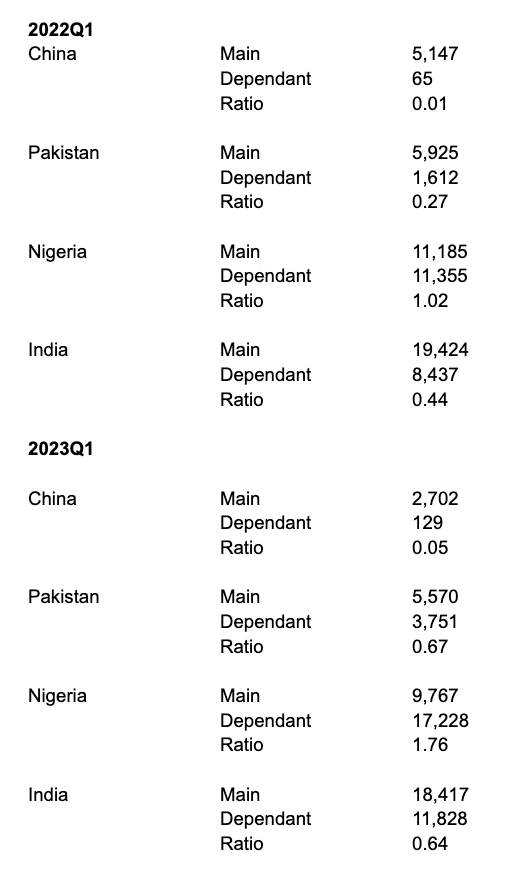

2022Q1 saw 26,410 study holder dependant visas issued – a year later, the same quarter saw the number up at 40.022 – a remarkable ratio change from 0.47 to 0.83. That’s driven by almost no rise in the ratio from China, a gentle increase from Pakistan and India, and another dramatic rise in the ratio from Nigeria – now up at 1.76 dependant visas issued for every main visa holder:

It’s almost certain that ministers have had advance sight of these figures – and while there remains a debate about whether the solution here is supply side change and investments in facilities and accommodation, or demand side changes of the sort we’ve seen emanate from government, it’s fairly clear why those involved have reasoned that something had to be done.

Some charts

Here thanks to David Kernohan is a tableau that puts some of this into a wider context – blue shows student route dependents, orange shows student route main applicants, and grey shows everything else (other than your standard holiday-style visitor visas. which are omitted). You can look by any country in the world:

Looking ahead

The question now, of course, is what happens next. If the student to dependant ratio grows in the way that it has (again) here, even if main visa holder demand levels off, a major accommodation crisis in relation to families is coming – if that is you’re in a university town or city where there isn’t one already.

And that’s if demand levels off. You’d have to assume that the announcement that the PGT changes won’t happen until January will cause a huge spike in that demand, from those most likely to want to bring dependants to the UK. Avoiding very difficult debates about welfare, housing, facilities, school places and so on – especially when universities are not told if a given student has been given a visa – now looks pretty impossible.

As noted before here, the odd warning note from an international office is likely to be no match for the army of former students on social media and YouTube (many of whom likely work for agents) advising students to come anyway and hang out in AirBnBs while they find somewhere.

Beyond the bulge, we can trace back the PGT announcement on international students to the introduction of the points-based system and the graduate route, and the Home Office’s impact assessments on the graduate route and the student route respectively.

The reality is that it massively underestimated the volumes of international PGTs that would be attracted by the graduate route, it significantly underestimated the dependant to student ratio, because it was looking in the rear view mirror at the sort of students from the countries we used to recruit from – and it’s starting to look like it underestimated the numbers that would go at the end of programme rather than switch to skilled visa routes.

I’d add to that it didn’t bother addressing the human geography issues – calculating guesses on numbers is fine, but working out where they’ll be distributed matters too.

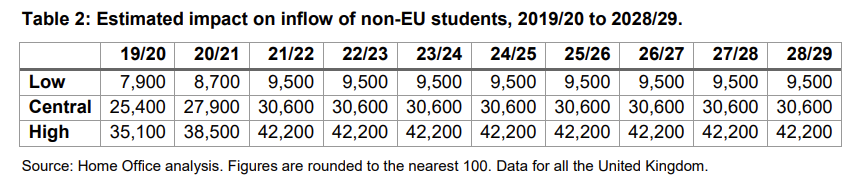

This table in particular – estimating numbers above the 2019 baseline – has turned out to be very wrong indeed:

This failure of statecraft, driven by an ideological anathema to planning, and an over-reliance on the magic of the market to supply what’s needed when demand is so high, is what’s got us here – and where we’ll go next.

We were already looking at 2023 beating all the 2022 records, and crucially this time next year we’ll have a net migration figure for 2023 that will still look very high, likely a weakened Rishi Sunak, a possible new UKIP/Reform breakaway that the Conservatives think needs neutralising, and so on.

On the way there in August and November we’ll have more record highs on visa issuance. And this time there won’t be a rabbit in the hat to pull regarding dependants.

Of course what we really need is a decent run at sustainable expansion, that can both respond to growing international and domestic demand, with proper planning that is mindful of local and campus infrastructure issues.

Unless universities get together and make it so, that won’t happen. If not, I’m sad to say that I suspect we may now be in a doom loop on international students and the immigration rules. And I suspect that anyone who’s waiting for a Labour government to call off restrictions or fix HE funding may need to correct their assumptions.

The ONS smoke-screening the reality of the numbers doesn’t help, though they have revised numbers upwards for the small boat arrivals.