Whether you’re looking at another university or SU’s website, catching up with colleagues at a conference or traipsing around in the snow on a study tour to Eastern and Northern Europe, one of the barriers to learning is what I always call the “they call a Twix a Raider problem”.

Subconsciously we’re on the look out for things that we assume to be similar, so that we can compare how those things are delivered, promoted, framed, measured, run or governed.

That allows for a dominant model of development – we all basically have the same scaffolding (in SUs a voice dept, a board, a CEO, elected student leaders, etc or in a university a VC, “student services”, estates and so on) and then we seek to learn how those things are done differently in practice through support, culture, training or whatever.

The problem is that sometimes, even though the Twix looks like a Raider, it really isn’t. And if you eat a lots of Twixes, learning about Raiders might be worse for your learning than if you’ve never had a Twix at all.

A load of Bologna

Let me explain. On our SU study tours in recent years, we’ve always been on the lookout for examples of innovative practice over educational quality and student voice.

One comforting bit of foundation is the Bologna process and the norms of quality assurance that apply as a result – not least the centrality of student voice in external quality review that England appears to have been recklessly moving away from in recent years.

So on this year’s trip, I was interested by a focus for many of the SUs on student rights; intrigued by the way in which many SUs’ reps seemed to be focussed on the evaluation of programmes rather than just passing on student opinions; fascinated by the close links between SUs’ rep systems and their democratic and policy making structures; and impressed by the numerous detailed education policy agendas that had been developed over time by those reps in those structures – all things that SUs in the UK could potentially adopt.

Probably the most exciting version of all of that was in Helsinki, where an encounter with the university’s strategy team (ably described here by Limerick’s Dáire Martin) described a system rooted centrally and deeply in the university’s vision of students as citizens and university as community.

The staff who presented to us had just been through a review of student representation and participation in university decision making – and inevitably the awarding of core academic credit to the reps, paying (some of) them for their time, and taking steps to ensure they feel more powerful and effective through better support and comms caused all sorts of scribbles in the notepads from our lot – albeit that it sounded like a lot to do in the middle of a funding crisis in a large university back in the UK.

But on the walk around to the SU later that afternoon, something wasn’t adding up.

The numbers don’t add up

At the meeting the university had said that there were about 300 reps. That seemed on the low side for a university of more than 30,000 students – but I chalked that up to a tendency to run quite large degree programmes with a considerable amount of study path flexibility within. More detailed degree transcripts also help reduce the number of what many UK universities would often describe as distinct “awards” and programmes.

But on that walk I’d remembered that he’d said that most programmes’ steering groups not only have a couple of student reps, but a couple of deputies too – all appointed by the SU through its impressive Halloped recruitment portal, shared with two other SUs in the city.

He’d also said that there were plenty of reps on the university’s big central bodies (the Board and the “Collegium” – equivalent to Senate or Academic Board) and countless working groups, steering committees and project boards.

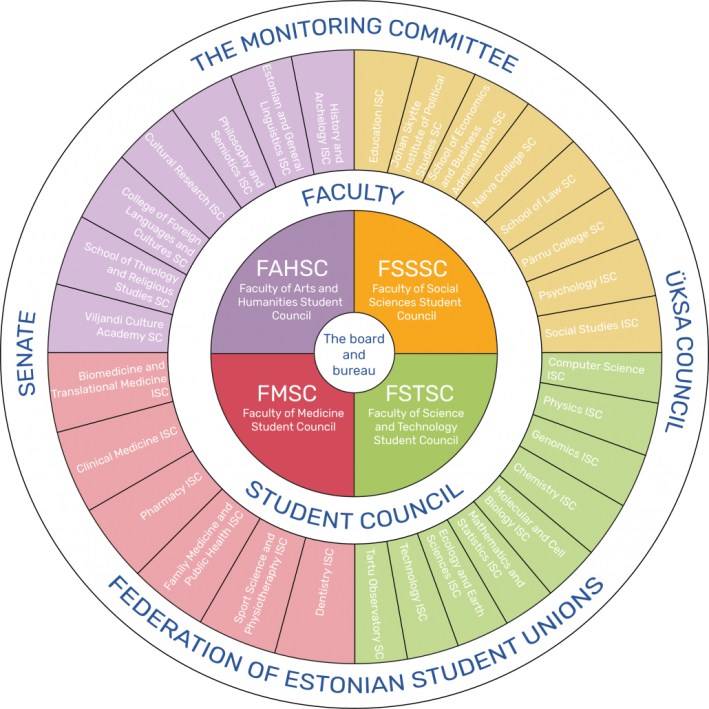

Flicking through my phone for photos of slides, I was also taken back to Tartu – where the SU’s council was made up of both all of its academic voice reps and those from faculties. Estonia’s national university is more modest in size – about 15,000 students – but I still couldn’t fathom how they were fitting all of their reps in the same room, let alone run effective policy and decision making structures.

What has therefore been nagging me ever since is how on earth, in Helsinki, all of that came to just 300 reps. But digging further on my return to the UK, I’ve worked it out. In this case, the Raider might taste like a delicious version of a Twix, and it’s certainly more expensive – but it’s not the same.

Every course has a rep

In the UK, the unspoken scaffold assumption is that as well as some feedback mechanisms, there’s one or two “course” or “class” reps on every course, for every year group. It’s been this way for decades, used to be pretty much mandated by the QAA, and while some SUs have faculty or school based positions (some elected, some appointed; some in a coordinating role and some in a representative role) the underpinning assumption on which people build distinct training, framing or support is pretty much the same.

But what’s clear across the continent is that that is not the case in lots of other countries. Student reps are on the bodies where decisions are made – at Helsinki, for example, degree steering groups supervise the curriculum, resolve the annual teaching schedule, define the framework for the courses taught in the schedule, resolve which modules are compulsory for everyone, determine what kind of study material and teaching methods are used on courses and set the methods to complete modules that each course has.

They’re the bodies whose feet are held to the fire over how long students are taking to complete, their satisfaction in the Finnish NSS, look after the culture of community in that part of the university, initiate subject-based development projects over curricular, co-curricular and extra-curricular activity, and generally translate the broad ambitions in the university’s strategy into practical action.

The four faculty bodies (“councils”) – all of which have at least four student reps (and deputies) then develop teaching and research at the faculty, oversee quality management over research and teaching, engage in partnerships, look after interdisciplinary work in the faculty, make decisions over degree requirements and student admissions criteria, and develop longer term plans.

And the Collegium and the Board do what you’d expect the Collegium and the Board do – albeit that HYY (the University of Helsinki’s SU) has just proudly announced that they’ve persuaded the university to adopt the “tripartite principle” on the Collegium, allocating equal seats to professional staff/managers, academic staff and students respectively.

The contrast with the common UK experience is stark. Most decent sized universities have hundreds, sometimes thousands of reps – with the SU often setting KPIs for the number of positions filled or reps trained, but rarely any measures on their effectiveness at influencing decision making.

We’re in the wrong room

In my numerous encounters with class and course reps at rep conferences over the past few years, one of the most common experiences shared is that whichever room they’re in, it’s almost never the one where decisions are made.

The rep toddling along to an SSLC is more likely to report things outside of the control of the people in the room – allowing a kind of temporary student focussed wallowing session over timetabling or facilities or whatever, where often those issues are not escalated.

The reps that stick it out and take it seriously are often presented with the painful paradox of the job – they’re told it’s vital to gather feedback from students, but when they present it they’re often told that that’s different to that which the data says, or accused of needing more responses to their surveys (or in some cases, banned by an over-zealous research ethics unit from even gathering student feedback in a systematic way).

And as I’ve noted here before, not only are few of them (jointly with students) evaluating the programme against a set criteria (we don’t mark students on how we reflexively feel, at least I hope not), most of them got involved for other reasons (that are usually about community building rather than quality assurance and enhancement) and they are obviously deeply uncomfortable about raising concerns over the one thing the people in the room could change – how those people teach.

Few report ever having “achieved” anything at the end, and many report that their meetings were like watered-down UCU branch meetings, sharing in moaning about “the centre” or “the VC”, but getting little done.

None of this should come as a surprise. Course reppery in the UK comes from a different age – when surveys, if carried out, were on paper; when data was scarce; when programmes (and universities) were smaller; when less practice was standardised; when modularity and semesterisation didn’t exist; when it made sense to assume that student communication should occur through a rep; and when more university decision making was devolved. But the internet, the efficiencies required in a mass HE system and the realities of student life now mean that the scaffolding makes no sense.

There are, I suspect, too many course reps.

Contrast that level of structural reppery with the way that professional services have developed in the UK. In few universities would I find a proper board, with student input, that looks after counselling, or a particular campus, or a new project or a IT initiative.

Much student input into that is rammed through a quarterly “student experience committee”, or input is gathered through focus groups (not the same) – or if there is a working group or committee, the expectation is that that will be another hour of out of an already busy sabbatical SU President or Education Officer’s diary.

It’s notable, I think, that both in more formally democratic systems and in systems we’ve seen that are more managerialist on the continent, there is a huge breadth of students that are recruited to contribute – and it’s hard to conclude, from what I’ve read, that the quality of student input in each of those areas is anything but more impactful and more effective.

Put another way, in some ways, in the UK there aren’t enough student reps giving input on all the decisions that do impact their experience, study environment and learning.

We need more discipline

But something else that strikes me is about subject. Few universities are single, coherent communities these days. They are communities of communities – made up of students who share characteristics, hobbies, passions, backgrounds and subjects. Yet in comparison to Europe and its tendency to be better at associative activity, UK students’ unionism has tended toward the hobby or the sport at the giant Freshers Fair.

Most SUs we’ve seen have effective, less formal and easier to engage with substructures at what we would call departmental or school level – that combine social activity with careers work, curriculum development, extra and co-curricular activity and project work. That those bodies are invited to those boards I was talking of at Helsinki to contribute alongside the formal student reps, and are just as likely to meet the Head of School or Head of Department, should tell us something about the purpose of the scaffolding that both SUs and their universities should be considering when trying to build belonging and community.

Crucially, what struck me during a side conversation with one of the University of Tallinn’s central student officers (who last year was leading a departmental body) was that she represented someone who could work with the staff in her area at the right level to advocate for change, with the support of her committee, at a more granular level than the average UK sabbatical level – sharing responsibility for the culture of community in it, but at a level of confidence and capacity that a lowly course rep never could.

And given that the emerging culture of quality these days is much less about auditing systems, structure and paperwork, and much more about impact and targeting interventions on departments who are reviewing their data, it’s no surprise that the new rule at Helsinki is that student reps are explicitly not expected to gather student feedback – their role is to spot the trends in the data and survey work that’s there, and feed in on interpretation of that data and decision making off the back of it.

Arguably the most interesting version that was back in Estonia. Donkey’s years ago when Tartu was tiny, it had the sort of rep structure we might see in the UK – but over time has evolved to embedding a deep culture of feedback in programmes which sees students required to give to feedback on a module to pass the course, and in the process reflecting on their own independent study too.

The university publishes, on the intranet, all module evaluation results, those include what the module leader is doing in response (closing the feedback loop), and there are systems for raising common issues up the chain. And it’s all because deep in the university’s strategy is the idea that to be engaged as a student, you have to engage in how that process is working – so filling in the survey and learning from it becomes universal, compulsory and normalised rather than a pain in the backside.

That then means that so-called “institute” and faculty level student reps influence decisions where they’re made off the back of that culture – and because they all fit in a room, the link to the SU’s policy processes and democratic structure means that the SU itself feels significantly more representative of students’ concerns and more sophisticated as a policy influencing actor.

Partnership with who?

One other thing I’ve noted is the tetchy relationship between SUs and university student engagement officials (and sometimes departments) in the UK isn’t really a thing in these systems.

It’s accepted in principle that SUs will appoint (but usually not elect) all student reps (including those “change agents” and 100-strong focus groups universities seem to like these days) – but because the scaffolding efficiently supports the kinds of project and subject-specific work that I know most PVCs need to see happen when they spot a problem in the data, it frees up what we would call university engagement staff to work on the issues that come up.

So sum it all up, and my twelve reflections are as follows.

- First is the need for fewer, more informed, better supported academic student representatives who are able to impact decisions where they are actually made, and where the real accountabilities are.

- Second is no expectation that they themselves will have gathered feedback – their role should be to supervise it happening, spot patterns in the data, intervene in the student interest and contribute as real partners. And nor should the expectation be that reps will communicate the university’s messages “down” either – get a proper comms strategy.

- Third is establishing, in a way that is rooted in the university’s strategy and vision for the development of students as active learners and citizens, the universality of a culture of feedback – and the closing the feedback loop.

- Fourth is the symbolic importance of partnership and letting the SU run the selection and training for representatives, student change agents, working group members and so on – as long as in return, the SU’s systems and structures are more targeted, less election-focussed (democratic appointment is not a contradiction in terms) and more flexible – and crucially able to manage diversity in a way that “the confident ones stand for election” can’t.

- Fifth is reward and (visible) recognition. So many of the systems we’ve seen either award academic credit for the participation – because students learn a lot from undertaking those roles – or pay them, because students shouldn’t be the only “equal” decision makers in a room who aren’t. Or both.

- Sixth is tying those student leaders closely into the culture of the department, school or whatever. As I say, universities are a community of communities, and the idea that students are engaged in the success of the department, the success of other students and the success of the discipline should be obvious when students enrol and meet their reps. Student tutoring would help here too.

- Seventh is that there should be broad, departmental standards on engaging with students outside of any “rep scheme”, and much more involvement of students in the (professional) services, projects and initiatives that allow them to share responsibility for others’ success. We might not “need” a busy SU sabbatical officer on a marcomms working group or the monthly managers’ meeting in student services – but we should have engaged students in those rooms sharing in the responsibility to make those efforts more student focussed and impactful. And using sabbs on disciplinary panels is just daft (we can’t find any other country that does this) – the right thing to do is recruit students through the SU and pay them for their time.

- Eighth is not abandoning the idea that students can and should volunteer to improve the culture on a course. If it was up to me, every student should serve in some way, and be rewarded for doing so. What won’t work is pretending that one course rep can also be a prefect, signposter, shop steward and amateur advisor all in one.

- Ninth is shifting student feedback at any level away from reflective “happy or sad” or “if you have any problems, raise them with the rep” messaging towards something much more closely linked to evaluating against quality minimums, the quality aspirationals, the university’s strategy and ambitions for the discipline. Students should share in the process of making quality judgements.

- Tenth is SUs considering linking a more effective set of student representative scaffolds to their democratic structures. It’s hard to say this, because I work with SUs every week – but too few SUs have a vision for education, too little democratic decision making is about the student study experience, and too few university level student reps have anything to ground their contributions in beyond their instincts or their manifesto.

- Eleventh is SUs and universities working closely to create the sorts of shared support that students need to foster their own communities around subjects or disciplines. I feel confident in saying that the UK has the weakest culture of student-led social and representational activity organised at that level in Europe, and the belonging benefits – let alone the educational and developmental ones – would be huge. Not only are they better at responding and innovating in the student interest than career staff both in SUs and universities, but when students see other students leading, new students want to be them some day.

- Twelfth is a principle we picked up across our visits – never, ever, ever letting a student in a room be the only student in a room. Whether at governing body level or programme level, working on something huge or tiny, having more than one student in a room boosts their confidence in contributing in a context of huge differentials in cultural and academic capital, age and experience – and helps deal with their (on average) high levels of (social) anxiety too. The sector either wants student reps to be effective or it doesn’t.

Making partnership real

But finally, I think I’d say that this does all require, in any “rep review” that might be dumped on the desk of a university quality manager or SU voice coordinator, building and enforcing a real culture of partnership across a university.

I know everyone says words to that effect (I’ve read all the TEF submissions) but I mean one that goes beyond a university’s managers meeting the trustees of an SU charity every six weeks, and instead involves those partners modelling, driving and enforcing behaviours of trust in students in all corners of an institution.

What I mean is that if a university wants to address issue X, or achieve objective Y, far more students than the six who won a popularity contest in March should share in both picking the things to address or achieve, designing how to address or achieve them and be involved in actually addressing or achievement them. And yes, I’m counting the difficult and confidential stuff as much as I am the fun and aspirational things.

The “efficiencies” that will be required in the coming years in UK HE will make it harder than ever to get beyond instrumentalist, transactional, provider and consumer “lay it on a plate” relationships with students.

But the idea that students are citizens, that the university is a community (of communities), and that they have responsibilities to each other, is not only vital to retain and reform educationally, it is also likely to make the reduction in the resource available to support students in the coming years that little bit more bearable.