Don’t be fooled by Labour’s soft words.

In its election manifesto, they’ve set a challenge for the sector – more finance is available, but the price will be a more interventionist government.

Is the sector willing and ready to rise to this?

The sector’s response to Labour’s manifesto consisted of relief at the promise of a “secure future for higher education”, and despair at the lack of any specific policy detail.

The space afforded to further and higher education in the Labour manifesto was small, at just 417 words. Yet the party has set a challenge for the sector, if you just read between the lines.

In return for this promised secure future, the sector should brace itself for a reorientation of its key purposes, and consider whether it will be willing to forgo some of its long-held autonomy.

A cautious manifesto

The manifesto is ambitious in its aims but cautious in its approach. Almost every commitment is predicated on first achieving economic growth. Tax and spending pledges are shockingly low – at 0.2% GDP, it’s lower than the manifestos of other parties, and of Labour’s previous manifestos.

Any sector hoping to secure additional funding will have a tough time. Labour, if elected, will inherit a stagnant economy, and multiple funding crises that include the NHS, schools, local councils, and prisons. Most, if not all, of these will need financial attention before the magic growth tree has time to sprout.

Starmer has made clear that if it comes to choosing between the NHS and higher education, then our healthcare system is miles ahead.

This means that prioritisation of funding is key. Labour will be assessing competing bids for investment by a number of criteria: need, popularity, strategic importance and returns on investment.

Proving these things – need, popularity, importance and returns – is going to be a challenge for the sector.

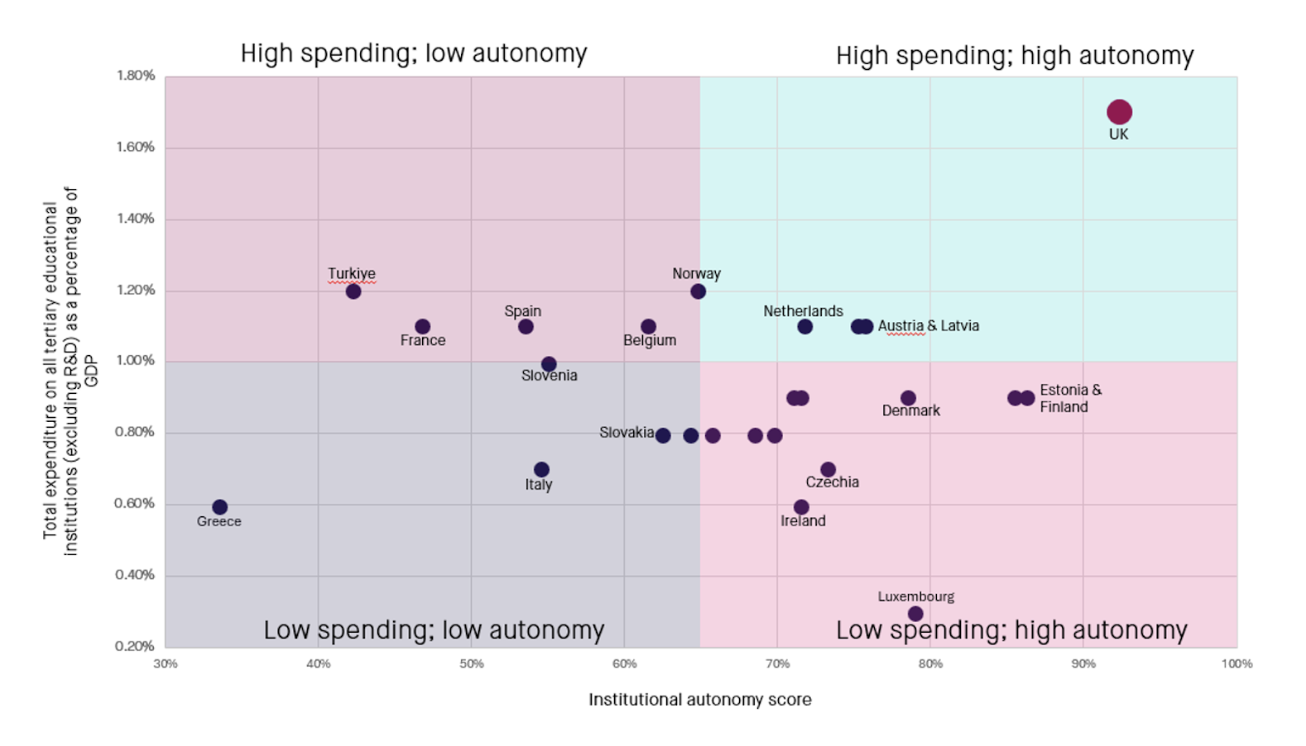

As I’ve previously written, universities have done well in the last decade, and overall spending is exceptionally high compared to other countries – higher than the OECD average (1.7% of GDP, compared to an OECD average of 1.0%), and the third highest globally, second only (of those measured) to the United States (2.2%) and Chile (2.6%).

It is hard to see the sector as anything other than relatively wealthy.

Making the case that the declining unit of resource from the tuition fee freeze will lead to poorer student experience or course quality will be difficult, given recent data showing that student satisfaction and their perception on value for money has increased.

At the same time, universities in the UK are afforded an extraordinary amount of institutional autonomy relative to other countries:

Perhaps partly because the argument of need is hard to make, increased funding for higher education is unpopular with the public. Funding for universities is the least popular use of education spending. Increasing tuition fees would be the simplest avenue for the state to funnel more money into the system, but as a policy it is so unpopular that it even ranks below National Service.

Polling isn’t everything, and if Labour won the election with the current predicted majority, then they could probably afford an unpopular policy or two. But they would want to see returns, and the data shows a mixed picture on what they could expect.

Participation in higher education has well-evidenced individual and societal benefits. The data is less convincing on whether we would see greater social or economic returns for further funding.

Given that the UK performs (almost) top for tertiary expenditure, you might also expect them to perform highly on other measures that correlate with higher education participation. In reality:

- The Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, Lithuania, Sweden, and Germany all spend less (as a percentage of GDP) but have higher graduate employment rates.

- Germany, Ireland, Lithuania and Spain all spend less but have a greater earnings premium for those with a graduate degree compared to upper secondary.

Again, this is not an insurmountable hurdle – universities are far from the only factor impacting employment and pay, and you can still make the argument for the social and civic benefits.

Lower performance than would be expected given spending in these areas also gives way for opportunities for improvement, and something a new government could take credit for early on. It is therefore unsurprising that the manifesto speaks about universities delivering more for the workforce, the economy, and for businesses.

Opportunities for the sector

A potential Labour government could deliver new opportunities for the sector, but universities must focus their efforts on battles they can win.

It’s hard to make the case that the sector is in dire financial need, and a blanket increase in funding across the sector (either through fee rises or otherwise) is both unpopular and probably unnecessary.

Despite this, Labour have promised a secure future for higher education. We have to assume this will include at least some changes to the funding system.

In lieu of fee rises, a fairer deal for universities, students and the taxpayer reads to me that a greater public contribution to higher education could be on the cards. There is an overall economic benefit to university funding – graduates earn more than £11,000 compared to non-graduates.

They are also less likely to be unemployed, and likely to be more productive. There are wider, non-economic benefits to both the individual and to society – less crime, greater political stability, greater social mobility, more civic engagement and volunteering, and increased mental and physical health. A rebalancing of the public-private contribution doesn’t seem farfetched.

The price to pay

But an increased public contribution will not be condition free, and I’m not convinced the sector has realised this yet. Labour recognise the strategic importance of higher education – but the role Labour sees the sector playing and the role the sector wants to play are not necessarily in sync.

What we can infer from the manifesto is that Labour will want universities to:

- Deliver more on skills and employability, shifting towards a focus on delivering for the economy and businesses.

- Focus specifically on building and upskilling a “British” workforce, and a move away from overreliance on international student fees – this is not said explicitly, but given Starmer’s aims to reduce businesses reliance on immigration.

- It would be strange to assume that this will not also extend to universities (note the involvement of the Migration Advisory Committee in Skills England).

- Be more locally focused – greater involvement in delivering for their local area, tying into greater devolution of skills.

- Raise teaching standards – implicit is that they feel the TEF has not succeed, they may instead want to consider common assessments, teaching inspections, or a ‘learning gain’ survey to monitor quality.

The inclusion of “strengthening regulation” is significant – Labour is setting out the cost the sector will have to pay for this secure future. For a secure future the price will be reduced autonomy.

For all the talk of wanting a political party in power that recognises the public good of higher education (and therefore invests more public money), I don’t think the sector has thought through what that would look like in practice.

A greater public contribution will see in a more interventionist government than the quasi-free market of the last twelve years. Increasing funding for higher education across the board, or increasing tuition fees, are both unpopular policies.

Funding for specific provision or activity that supports skills, opportunities, or local communities, targeted at the institutions that are more financially vulnerable, will be an easier package to sell, both to the public and to the party.

For the last decade the sector has been having a great time having their cake and eating it, but reading between the lines of the manifesto, this won’t last for much longer – universities must deliver more for the taxpayer, for businesses, and for the economy. Is the sector ready to rise to the challenge?

Interesting piece but there are a number of conclusions like this: “… I’m not convinced the sector has realised this yet”. What’s the basis for this? Is there evidence “the sector” isn’t considering exactly this, among various other scenarios?

If the SMF (and Public First etc) has done this between-the-lines reading, I would assume that universities up and down the country have done also.

The sketch of the various interventionist approaches government might take in terms of returns on investment or how to distribute investment seem plausible, but I don’t think “the sector” would find any of them particularly egregious.

The overall argument here has to be correct – a Labour government will not simply concede to the plea from universities which seems to be “give us more money and just leave us alone” because we are important. Universities are important, but productivity and economic growth are flat-lined and the graduate premium has weakened. Given that, the article rightly points to some of the expectations a new Labour government might have, particularly asking for more focus on skills and local labour markets. The missing piece for me though is the Labour manifesto commitment to a tertiary future, because I’m sure… Read more »

A few follow-up thoughts. Stimulating demand for standalone Level 4 and 5 is as much a demand on employers as the education sector and, indeed, consumers. We have one of the lowest levels of subsidy of employer subsidy on training and development in the OECD and until some of that balance shifts demand will always be placed upon Level 6 and above as young people, quite rightly, see this as the only way of making tertiary education work for them. That subsidy might also work better in retraining than it does now – we’re at the point where we desperately… Read more »

Thankyou for opening up a debate on this important question. But I do wonder on what planet have the Social Market Foundation been living on? Thanks in part to the groupthink of such pro-market think tanks, for several decades now UK universities have been doing almost nothing else but jump through ever-changing hoops set by governments of both main parties with a terrifyingly instrumentalist view of education. In reality universities have already largely long lost their autonomy, in favour of crudely serving skills and employability agendas, ie the short-term training needs of big business – who however refuse to pay… Read more »