The higher education sector is in Liverpool around the fringes of Labour Party Conference – but its arguments are getting a little lost.

That’s not a reflection on some of the high quality discussions that have taken place or the room bookings made, but about the increasingly tired and fuzzy asks being advanced.

It’s easy to hear calls for more investment – but harder to work out exactly who or what would benefit from it, and how much it might actually cost.

As such the “please sir, can I have some more” message is fading into the background of a cacophony of calls from every bit of austerity-hit Britain. The return of maintenance grants, improving per-student funding, easing the burdens on graduates – they all seem to be falling on distinctly deaf ears, and none of them seem to have any hard numbers attached.

That may not have been as big a problem in previous HE resource crises for three reasons.

The first is that the sector is now so big, when someone calls for something on the shopping list, it’s hugely more expensive than it was in the past.

The second is that the public finances really are in a dire state. Right now public debt, which eclipses nearly the size of the entire economy, stands at 98.8 per cent of GDP. Couple that with shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves’ CCHQ attack-neutralising Overton window of not raising taxes and not spending money she doesn’t have, and the wriggle room for improving things disappears.

Given economic growth is “the thing” that will pay for…things, some in the sector believe that a promise of higher education stimulating economic activity is the way to persuade Reeves to open the purse. Others hope that rewriting the economic rules to redefine spend on at least some of education as (human) capital investment might loosen things up.

Yet neither of those feel like things that will impact student, university or graduate budgets in the near future, and certainly won’t happen ahead of a general election.

But arguably the biggest problem for the more-money-message is the way that it’s been obtained in the past. If we look back at sector wins in recent history, they’ve all involved shifting the costs of HE onto graduates. The introduction of fees in 1998, and their subsequent increases in 2004 and 2010 were all a sort of human PFI – paying for more places and better funding by shifting more of the costs onto graduates.

Even the increase in student maintenance levels in the middle of the last decade involved the same trick – more cash in the back pocket was paid for by loaning more of it and granting less of it.

As such, the big bind that the sector now finds itself in is the scale of the changes that have been introduced to the system over the past two years. Because they’ve also involved shifting a big wedge of the cost of HE onto graduates – only this time, neither students, universities nor graduates have benefitted.

Stealthy moves

Towards the end of the pandemic, to little fanfare and facing the most muted of opposition by the sector, former universities minister Michelle Donelan (at the behest of a Sunak-led Treasury) slipped through changes to the repayment threshold for graduates, the term length of undergraduate loans and to interest rates.

As a result, the IFS calculates that the long-run per cohort cost of higher education in England has gone from £6.8bn to £4.1bn. In other words, the Treasury has managed to make higher education 40 per cent more expensive for those who participate in it, while publicly using the freeze in the tuition fee sticker price to divert attention from the raid.

In 1998, 2004 and 2010, the sector might have expected at least some of that £2.7bn per cohort saving to fund university costs, student maintenance or relief for graduates. But the Treasury has had the lot – and almost nobody seems to have noticed.

IFS now calculates the famed “RAB charge” – the amount of any loan that the government doesn’t expect back – to be down to 13 per cent. There are therefore vanishingly few ways of making that subsidy even lower to pay for some other part of the system. The trick can’t be pulled again.

This gordian knot may help to explain why shadow universities minister Matt Western has been touring the fringes accepting that there are problems for students, universities and graduates – but when pressed on solutions and proposals, can only say that the issue is keeping him “awake at night”.

Raising tuition fees might be the answer. But even if you did so by loading the debt on the most well-off, the totemic nature of the sticker price is the biggest political problem in the post-2012 system – and is why shadow secretary of state Bridget Phillipson has been quoted in Liverpool as arguing that raising the fees cap would be a “very hard argument to make” – both to the public and, presumably, to Rachel Reeves.

Thus far, the only intervention that seems to have had any purchase is that from London Economics – so when Phillipson says that modelling she’s seen within the existing envelope could deliver a “more progressive system” that delivers “month on month cuts” in terms of the contribution required of graduates, she’s referring to proposals to have a “stepped” repayments system, some grants for the poorest on top of current entitlements and removing Donelan’s expensive abolition of “real” interest on student loans.

Over and overton

So if, at least in the short term, that Overton window is unlikely to shift – and if, in the short term, Phillipson will at least talk about being open to changing the distribution of what’s left in the envelope – the question is what sort of proposals might make a difference in the next few months and therefore the next few years.

And key to understanding that is the importance and impact of that interest rates giveaway from Sunak when he was Chancellor.

It’s true that the stealth changes have allowed the Treasury to save £2.7bn per cohort by dumping debt onto graduates. But the distribution of those changes has not been equal – and in reality, the inclusion of the interest rate change looks set to hugely benefit the richest of those that actually take out loans.

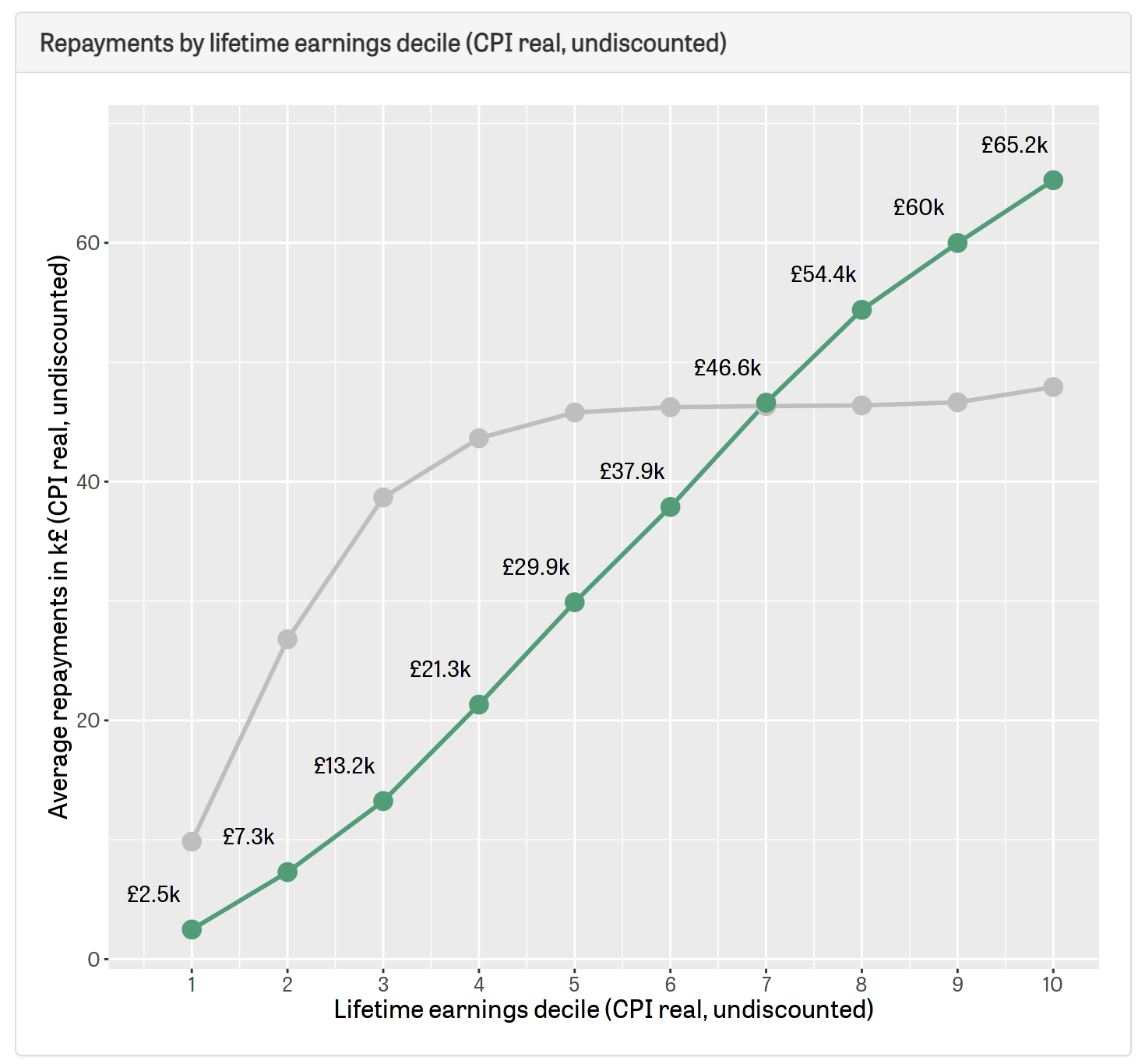

Here’s an IFS chart that compares the September 2023 system (the green line) with where we were a couple of years ago (the grey line). You’ll see that with modelling and inflation discounting, a graduate in the third earnings decile will pay £23,000 more for their higher education – while those in decile 10 will pay about £20,000 less.

IFS calculates that that interest rate component alone is worth £4.8bn per cohort. So if, in the short term, we’re having to operate inside Reeves’ Overton envelope of fixed fees and no more money, the question is then whether that £4.8bn might be better spent on something, or someone else.

What a relief for everyone

Let’s say we constructed a package that gives some relief to students, some to graduates and some to universities. If, for example, we use the IFS calculator to look at a version of the system without the interest rate cut but includes:

- An (Augar-proposed) living wage-indexed maintenance package, where everyone can borrow the maximum amount (Wales style)

- A reduction in the repayment rate above threshold for graduates to 8 per cent (from 9 per cent)

- An increase of £2,500 per student on the teaching (strategic priorities) grant

- A £500 per-student mental health fund, the use of which would be directed by students

- Raising the repayment threshold to the median real terms salary for graduates (£26,500)

…that package would be fiscally neutral, and actually reduce overall graduate contributions for (the bottom) earnings half of all women from where they’re projected to be today.

With a few amendments to the above, Labour could throw in a maintenance grant here and there if it wanted something else that’s totemic to go into the election with, and in the medium term moving towards some of the more attractive features of a graduate tax (preventing better off parents from escaping interest by paying upfront) can also be considered.

(If the average private day school is now charging £15,655 a year in fees, then the upfront tuition fees for the university they’re trying to get their kids into being held at £9,250 is an absolute bargain.)

And the T-grant changes would help it get control over what it’s spending (and where), and would at least in theory allow universities to reduce some reliance on international students, which is heating up the housing market for everyone.

The choice at the coming election

Politics is always about choices. A proposal like the one above would create a dividing line – between the Conservatives giving a bung to rich men in their fifties, and Labour at least in the short term addressing acute poverty in the system now – while still managing to deliver a system that is more progressive.

The point isn’t so much about the precise numbers above – and there’s various other things to think about – including behavioural modelling, what to do about the crisis in the private rental sector, the eye-watering profits being made out of private (usually franchised HE) and a need to increase numbers soon for demand reasons.

The point is that by cancelling the expensive cash giveaway to rich graduates that the interest rate cut represents, Labour would have wriggle room – and that means it could move pretty swiftly to relieve (in the short term) problems deep in the system for pretty much everyone (students, universities, and new graduates) – all while a better system is devised.

Of course the thing that would remain in the above modelling is the recent switch from a 30 year term to a 40 year term on loans. It remains the case that the “debt” is going to continue to grow, and will look both increasingly unsustainable to the Treasury and to those trying to save for their old age in their fifties.

But kicking the can down the road is where we are anyway – and a much wider look (as has happened in the US) at long-term student loan debt will have to happen at some stage.

It’s just not clear why university staff, students and young graduates should all have to go hungry while Treasury wonks get their act together. The sector needs to start lobbying for realistic and politically palatable solutions now.

I would be impressed if the sector openly lobbied for anything! UK HE is conspicuously silent whenever the ‘price’ of education is discussed in public. Universities are too scared of speaking up, and yet we’re supposed to be creating and sharing knowledge – why can we not do that about our own institutions? We need to be open, about what funding we need and how we spend it, we need to show the value for money for every person in the UK and the real implications of an impoverished sector. This information needs to come individual universities – ‘UUK’ or… Read more »

The other option could be lobbying for changes that might reduce costs for the sector, or help them drive efficiencies. E.g. some kind of work around for VAT relief on shared services? (Do two (or more) universities in the same city really need all their own specialist professional services and support staff? The answer in many cases is ‘no’, but the additional VAT costs currently make it prohibitive to share.) Or specific changes that would vastly reduce the data and reporting burden. The sector would find open ears for technical policies that don’t cost any extra money, but allow them… Read more »

Student loan interest rates seem to be a subject which divides professionals from the public. The Post 18 review said it would be “imprudent and wasteful” for government to cut the interest rate but that’s exactly what the Donelan reforms did for the 2023 intake. On Money saving expert site, Martin Lewis says it is “wrong in principle” for student loans to have higher interest rates. Often when mainstream media outlets run stories on student loans, they find graduates in their twenties whose debt has gone up despite the repayments they’ve made. Interest is often the cause. The fact that… Read more »

Why is this an industry that shuts down for 3 months every summer as it did in 1420? Deliver T over 40 weeks rather than 30 and students save on accommodation costs…

The fundamental problem with the 2012 loan-based system for funding undergraduate education is that it places an upper bound on the amount paid into the system by the most well-paid graduates in that nobody pays more than the cost incurred by their own individual degree. This is why, when the government responded to the Augar proposals to reduce the overall cost to the exchequer, the burden would inevitably fall on the least well paid graduates as higher paid graduates were already making a repayment at that upper bound. In the event, the priorities of the Government ensured that the actual… Read more »