How far down a vice chancellor’s in-tray does philanthropy sit these days? Is it the “icing on the cherry on the cake” for universities – or a baked-in ingredient of the cake itself?

Giving to universities is not, as some assume, an American invention. It has a long and honourable tradition in this country – the earliest gift we have found was in 1284, a donation of 50 marks to the University of Cambridge “for the support of poor students.” Most universities are, after all, charities.

A decade ago, the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) commissioned More Partnership, under the leadership of Shirley Pearce, to produce a status report on fundraising in UK higher education. That report showed that giving to universities was accelerating in volume and impact, in step with increasing investment and expertise among professional staff.

And it was not just the preserve of the ancient and elite institutions. Pearce’s number one recommendation was that all institutions should develop advancement plans – including fundraising, alumni relations and communications activities – based on a clear understanding of their own distinctiveness, goals and particular opportunities. The report concluded with a series of ambitious predictions for the decade ahead. But how have they stood the test of the ten distinctly unpredictable years that followed?

Accelerating ambitions

A new report revisits the original Pearce findings and analyses a decade of fundraising performance across the sector. Accelerating ambitions: a decade of giving to higher education and how it informs the future is the combined work of the Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE) and More Partnership.

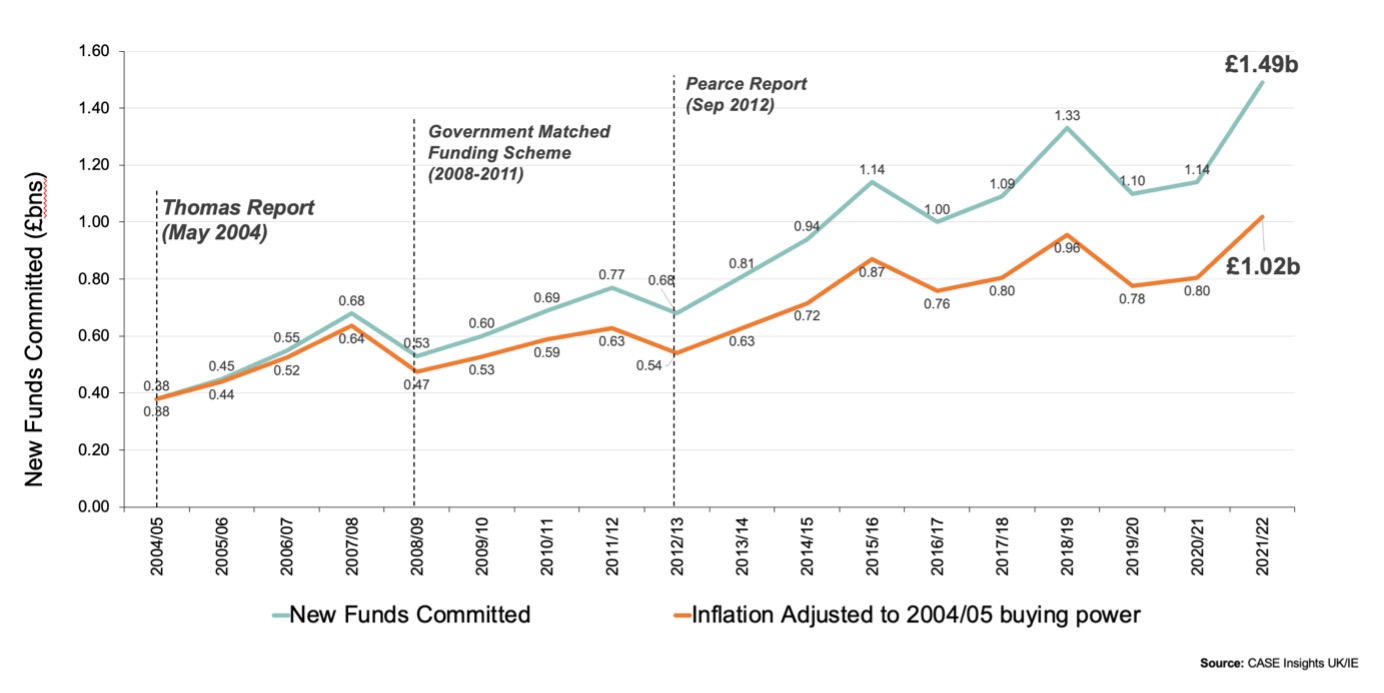

The results are remarkably encouraging. Despite Brexit and Covid, despite geopolitical turbulence and mounting student debt, UK universities have almost doubled the annual amount fundraised in a decade, to a record £1.5bn in 2022. This chart illustrates the growth since 2004, marking three seminal moments for the advancement profession along the way.

When investment in universities is so vital but the usual sources of funding so constrained, many vice chancellors have found that philanthropy is one of the few levers within their grasp to lift their strategic ambitions to a higher level.

In the ten highest performing institutions, new funds committed philanthropically rose to a record average of 10.4 per cent of overall turnover in 2022. This is material. In those institutions, the days of the icing on the cherry on the cake are long past. Philanthropy is something they can count on.

Records continue to be broken, from Ulster University’s first £1m+ gift to appoint its inaugural Professor of Medicine, to the “supernova” gift of £50m to the University of Strathclyde, to the completion of the outstanding £3.3bn Oxford Thinking campaign for the University of Oxford. Success creates confidence and fosters ambition for the future.

No longer the preserve of the elite and the ancient

Not everyone can bake the same cake, however, as a leading advancement professional told us in the research for the report. The pace of higher education philanthropy continues to accelerate – but the group of participants has become elongated. As Wonkhe reported in May, in response to the 2021–22 CASE-Ross Support of Education survey, the strong performance in fundraising among some institutions can mask concerning fragility in others.

But all institutions can benefit from philanthropy. Our detailed analysis of the data shows that meaningful and impactful fundraising programmes are to be found across the sector. The factors contributing to variances in fundraising success within relevant institutional groups are explored, rather simply highlighting the differences between these groups. One group that has shone in their efforts has been the specialist institutions, with a remarkable 255 per cent growth in annual funds raised over the decade. Their ability to understand the motivations of their supporters and to focus on a clear case for support is something to note.

There remains a correlation – as Pearce found – between the number of fundraising staff and the philanthropic funds committed. The doubling of annual new funds committed since 2012 has been powered by a fundraising workforce that has grown at only half that rate (by 47 per cent in the last decade). How much further could we go, if fundraising staff with the relevant talent and expertise were available to match the demand?

As philanthropy continues to step up, how do we create an environment in higher education where fundraising is taken more seriously in those institutions that have tried and stumbled with an advancement operation – we see some dispiriting serial start-ups – or who have been distracted by a battering from the urgent over the important? How do we guard against philanthropic trends exacerbating sector stratification, with the net effect being that the best resourced corner the market in cake?

Fertile ground for philanthropy

Creating the conditions within which fundraising (and the people who power it) can flourish must be a sector-wide commitment. But how to do this, and who should be responsible?

We find that a set of ingredients are commonplace in all successful advancement operations. Beyond those, institutions have choices to make to tailor their philanthropic strategy to fit their needs – and we share a series of playbooks for different institutional contexts.

Undoubtedly some of this must be driven internally through leadership vision and commitment, through training and progression routes for advancement professionals, and through more senior advancement professionals having a seat at the top leadership table.

We predict that in the coming decade that the most impactful philanthropic propositions will increasingly involve collaborations across and within sectors and institutions, opening the door to opportunities for those institutions less able to resource their own advancement efforts. Corporate collaborations are a developing frontier for university impact, and acting now to increase legacy giving can unlock real rewards.

The impact of philanthropy is high and its practice increasingly sophisticated – but public awareness remains disconcertingly low. “Fundraisers rely on private voluntary giving being viewed as a good thing”, as Beth Breeze of the Centre for Philanthropy at the University of Kent commented for the report – “something that is admired and aspirational, not disparaged and therefore discouraged.”

Seven hundred years after that first known gift to Cambridge, the sector requires a concerted campaign to improve its “surround sound”, championing increased public understanding of giving to higher education institutions and the effectiveness of universities as a charitable cause.