One of the four objectives that Philip Augar has to address in the current post-18 review of education and funding is financial support for students – specifically, examining how disadvantaged students can progress and succeed in post-18 education.

For those students engaged in the traditional residential mode of participation, living costs are crucially important – evidenced in recent research from both the OfS and NUS’ poverty commission. Paying the rent for student accommodation is the largest part of this portion of spending, and is what a large number students and their parents will be focusing on after confirming their place to study in August. OfS’ survey of students’ perceptions of value for money in higher education found that 24% of students did not feel they were informed about how much everything would cost as a student, with accommodation costs one of the main factors cited. And earlier this year, The Times characterised rent as a “stealth tax” on parents, based on the difference between maximum student maintenance loans and the cost of student accommodation.

Killer questions

This poses an interesting question for policymakers. The cost of undergraduate tuition fees – and the loans required to cover them – are strictly controlled at the supply end, and while numbers are uncapped, this does give government and students some certainty over costs. But rent – the key living cost that maintenance loans are supposed to cover – is uncapped and uncontrolled.

There has been no meaningful policy intervention either on the supply or demand side to keep these costs under control. This is, of course, a subset of a wider policy issue – the housing “crisis” in towns and cities – but in higher education’s corner of this widespread issue, even if Augar and/or the government “fix” the parental contribution issue, the obvious danger is that the cost of student accommodation rises faster than ministers are prepared to let loans or grants grow by.

Navigating living costs

For students themselves, the question of living costs is not a straightforward issue to navigate. Even where providers advertise the student accommodation on offer, students often don’t know far in advance which choice in the range they will end up with. Student discount website Save the Student found in the 2018 edition of its annual survey that 44% of its 2000+ student respondents struggled to keep up with rent, with 45% saying their mental health suffers as a result of the cost of accommodation, and 31% finding it affects their studies. One in three students felt their accommodation was poor value for money.

Any economist would suggest that where there is a mismatch between supply and demand, prices will rise or fall- and we know that in recent years there have been mixed fortunes for universities in terms of student numbers. Some have benefited from the expansion in higher education and removal of the cap on student numbers, while others have struggled to maintain numbers in the light of other pressures.

We dug through the web archives to find the advertised prices of university-owned halls of residence at a number of universities to observe how different institutions had responded to the growth or decline in their student numbers in terms of accommodation pricing – and whether the changes fit the classic theory.

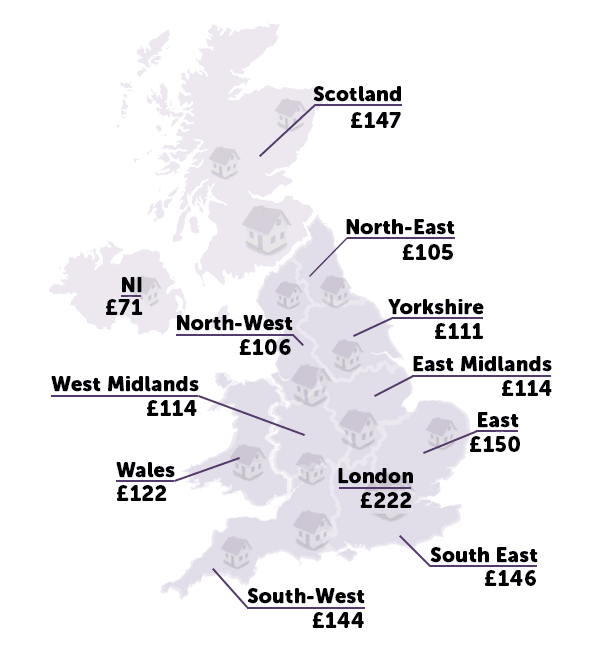

Average student accommodation rent by region, 2018 – Save the Student

Notes

Placed applicants are those placed for entry at a higher education provider – there is still a gap between the number of placed applicants and the number that end up studying at a higher education provider.

We’ve gone for range in terms of lowest and highest weekly prices for accommodation, which might not equate to lowest and highest across the academic year, depending on the duration of the agreement – most often between 39 to 52 weeks.

Price range

Aston University is among the ten institutions that grew the most in terms of placed applicants over the last eight years, placing 3065 students in 2018 compared with 1690 in 2010 – an increase of 81%. At Aston, the range in prices of halls of residence has narrowed over the years, starting at £51 between the highest- and lowest-priced accommodation on offer for the 2010-11 academic year to just £6 in 2018-19. The narrowing of the gap was primarily driven by jumps in fees for the lowest-priced accommodation – there were only incremental increases in the highest-priced accommodation each year. In the eight years considered the highest-priced accommodation only rose by £18.

Meanwhile at the University of Bristol, the gap has increased, mainly because of significant year-on-year jumps in the prices of the highest-priced accommodation. The price of the most expensive accommodation is now £215.90, more than double the price of the cheapest at £90.42, and an increase of 66 per cent on its price eight years ago. The University of Bristol – while not among the top ten fastest growing institutions – placed a massive 47 per cent more applicants in 2018 than eight years previous.

The University of Warwick has seen a much more modest increase of 12 per cent in the number of applicants placed over the last eight years. The price range between the least and most expensive halls has doubled since 2010, however, with the highest priced accommodation now more than double the price of the lowest at £181 compared with £76. The numbers are affected by Warwick’s method of increasing its housing capacity in the years 2016-17 and 2017-18 by providing twin rooms in accommodation that was previously offered to house one student.

Options

Another trend that could be missed by focusing on the lowest and highest priced accommodation is the effect of the number of options of student accommodation on pricing. The University of Warwick consistently offered a large number of undergraduate halls of residence (thirteen are on offer for 2018-19). While the price of the least expensive accommodation buildings have remained low for the last eight years, it is possible that the average price of accommodation for first-year undergraduates would tell a different story.

In comparison, both Aston University and the University of Bradford offered three or fewer accommodation options in the last eight years – the range in the price of accommodation at these institutions for 2018-19 was £6 and £9.03, respectively. The University of Bradford is among the universities that shrunk the most over the last eight years in terms of placed applicants, falling 23.7 per cent from an intake of 2,780 in 2010 to 2120 in 2018. In 2010, the Guardian ranked the University of Bradford as the most affordable for students based on spending – as per the Virgin Guide to British Universities estimates – and university-owned accommodation. At the time, the range between the lowest- and highest-priced accommodation at Bradford was £40.50, with the fall to £9.03 driven primarily by increases in the price of the least expensive accommodation to more than double its price in 2010.

Colleges

The University of Durham was mentioned as the most expensive by the same article. The University of Cambridge, like Durham, operates a college system of student accommodation. At Cambridge, where students tend to live in college student accommodation for the full duration of their degrees, the price range for student accommodation in 2017-18 was £75-195. This compares with an average of £131 across the East of England, according to the NUS/Unipol Accommodation Costs Survey 2014-16.

Despite changes in student numbers, universities have seemingly employed a range of strategies in their student accommodation pricing. Even among universities that have seen similar shifts in their student numbers, approaches to pricing have differed with possibly the most interesting strategy being the creation of “twin rooms”, similar to the US way of student living. It’s not at all clear that classic supply and demand mismatches tell the whole story – and there may be other factors at play, like the nature of any investment deal struck between a university and accommodation provider to finance the building, and the way in which first year accommodation is “sold” to students as being essential.

Getting a grip

If policy interventions are developed to get a grip of the issue on the supply or the demand slide, we’ll need a more accurate picture of the pricing of university-owned student accommodation, and we would need to look into average prices (which would take into account the number of rooms available at each different accommodation block) to tell us more about how many students are able to access rooms at the different prices listed.

Given that the days of HEFCE funding for capital are long gone, we need to know more about the way in which new builds are being financed, who profits from them, and how rent is set. And we have only looked at university-owned halls of residence here – it is much harder to predict what the picture for would look like if we touched on privately-owned accommodation. “Student accommodation nationwide is on a bull run right now” according to James Hanmer, head of UK student housing at Savills – suggesting that demand is outstripping supply. “The student housing market is robust… and well favoured by investors for its yearly rental growth and attractive yields”.

As long as the residential model persists in large parts of the sector, both policy-makers and students need to know much more about the realities of the costs of private sector accommodation that go beyond the surface level exercises and tables that dominate the press. And we will need to see a much more joined-up strategy between local authorities, government departments and institutions to ensure that that model is affordable for students.

Finance sits at the heart of this – I wonder whether ‘university-owned’ is an appropriate distinction – many universities’ portfolio of accommodation blurs the line with management and lease deals of various different flavours. Many universities have taken halls off-balance sheet – there was no capital funding for them – so various deals have been struck. Treating the whole portfolio as a unit, means rents in all halls can be used to meet the overall finance costs – not just the new builds. Meanwhile Savills are right – there is a lot of investment from all sorts of players looking… Read more »