About a decade ago now, there was a problem at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Across a collection of STEM courses, there was a significant “achievement” (attainment/awarding) gap between marginalised groups (all religious minorities and non-White students) and privileged students (caucasian, non-Hispanic participants who were either Christian or had no religion).

Psychology prof Markus Brauer had an idea. He’d previously undertaken research on social norms messaging – communicating to people that most of their peers hold certain pro-social attitudes or tend to engage in certain pro-social behaviours.

He knew that communications shape people’s perceptions of what is common and socially acceptable, which in turn influences their own attitudes and behaviours.

So he thought he’d try some on new students.

He started by trying out posters in waiting rooms and teaching spaces, and then tried showing two groups of students a video – one saw an off-the-shelf explanation of bias and micro-aggressions, and another where lots of voxpopped students described the day to day benefits of diversity.

Long story short? The latter “social norms” video had a strong, significant, positive effect on inclusive climate scores for students from marginalised backgrounds.

They reported that their peers behaved more inclusively and treated them with more respect, and the effect was stronger for marginalised students than for privileged students.

Then he tried it again. One group got to see the social norms video in their first scheduled class, and those students also got an email from the university’s Deputy Vice Chancellor for Diversity and Inclusion in week 7 of the semester, which reported positive findings from the university’s most recent climate survey and encouraged students to continue working toward an inclusive social climate.

The other group had a short “pro-diversity” statement added to the syllabus that was distributed in paper format during the first class. That pro-diversity statement briefly mentioned the university’s commitment to diversity and inclusive excellence. Students in this group did not receive an email.

As well as a whole bunch of perception effects, by the end of the semester the marginalised students in the latter group had significantly lower grades than privileged students. But in the norms video group, the achievement gap was completely eliminated – through better social cohesion.

What goes on tour

I was thinking about that little tale on both days of our brief study tour to Stockholm last month, where 20 or so UK student leaders (and the staff that support them) criss-crossed the city to meet with multiple student groups and associations to discuss their work.

Just below the surface, on the trips there’s an endless search for the secret sauce. What makes this work? Why is this successful?

Across our encounters in Stockholm, one of the big themes was “culture”. Gerry Johnson and Kevan Scholes’ Cultural Web isn’t a bad place to start.

- Stories and symbols were everywhere in Stockholm – Uppsala and Lund’s student nations tell a story of deep-rooted student self-governance, while patches on student boilersuits mark both affiliation and achievement.

- Rituals and routines were on offer too. Valborg (Walpurgis Eve) celebrations in Sweden bring students together in citywide festivities, and the routine of structured student influence meetings – where student representatives actively participate in decision-making – ensures that engagement isn’t just performative but institutionalised.

- Organisational structures help too. A student ombuds system that provides legal advice and advocacy, sends the signal that rights – mine and yours – are as important as responsibilities. Students’ role in housing cooperatives demonstrate how deeply embedded student influence is too – giving students a tangible stake in their own living conditions. And plenty of structures that include circa 2k students feels “just right” in terms of self-governing student communities.

- Control systems and power structures define the boundaries of student influence and how authority is distributed. Visibly giving student groups the job of welcome and induction – not “res life” professionals, “student engagement” teams or “events managers” – seems to matter. Causing student groups to lead on careers work – with professional staff behind the scenes, rather than front and centre – matters too.

In conversation, culture came up in multiple ways. One of the things that lots of the groups and their offshoots mentioned was that they played a role in introducing students to Swedish student culture – for international students, home students who were first in family, or just new students in general who needed to know how things worked.

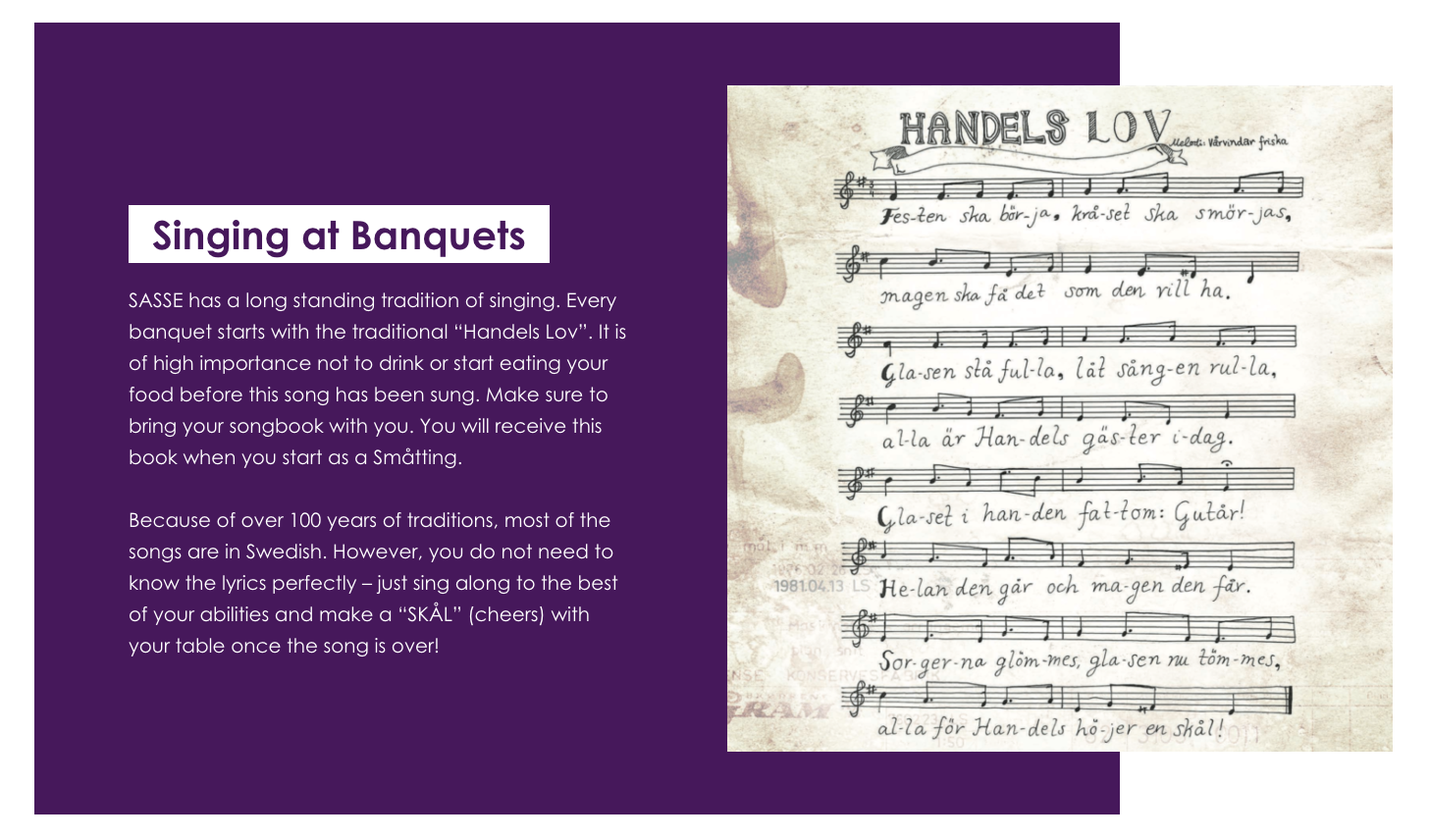

It came up in both an academic context and a social context. In the former, the focus was on independent study and the relative lack of contact hours in the Swedish system – in the latter, through traditions like “spex” (comedic part-improv theatrical performances created and performed by students), students wearing boiler suits with patches, or “Gasques”, where where students dress up, sing traditional songs, and enjoy multiple courses of food alongside speeches and entertainment.

But it also came up as a kind of excuse. As well as cracking out the XE app to work out how much better off students in Sweden tend to be, when we got vague answers to our questions interrogating the high, almost jaw-dropping levels of engagement in extracurricular responsibilities, both them and us were often putting it down to “the culture”.

“It’s fun”, “it’s what we do here”, “we want to help people” were much more likely to be the answers on offer than the things our end expected – CV boosting, academic credit or remuneration.

“Excuse” is a bit unfair – partly because one of the things that’s happened off the back of previous study tours is that delegates have brought home project ideas or new structures and plonked them into their university, the resultant failures often put down to a difference in culture.

Maybe that’s reasonable, maybe not. But we can change culture, surely?

Depth and breadth

Whatever’s going on, the depth and breadth of student engagement in activity outside of the formal scope of their course in Sweden is breathtaking.

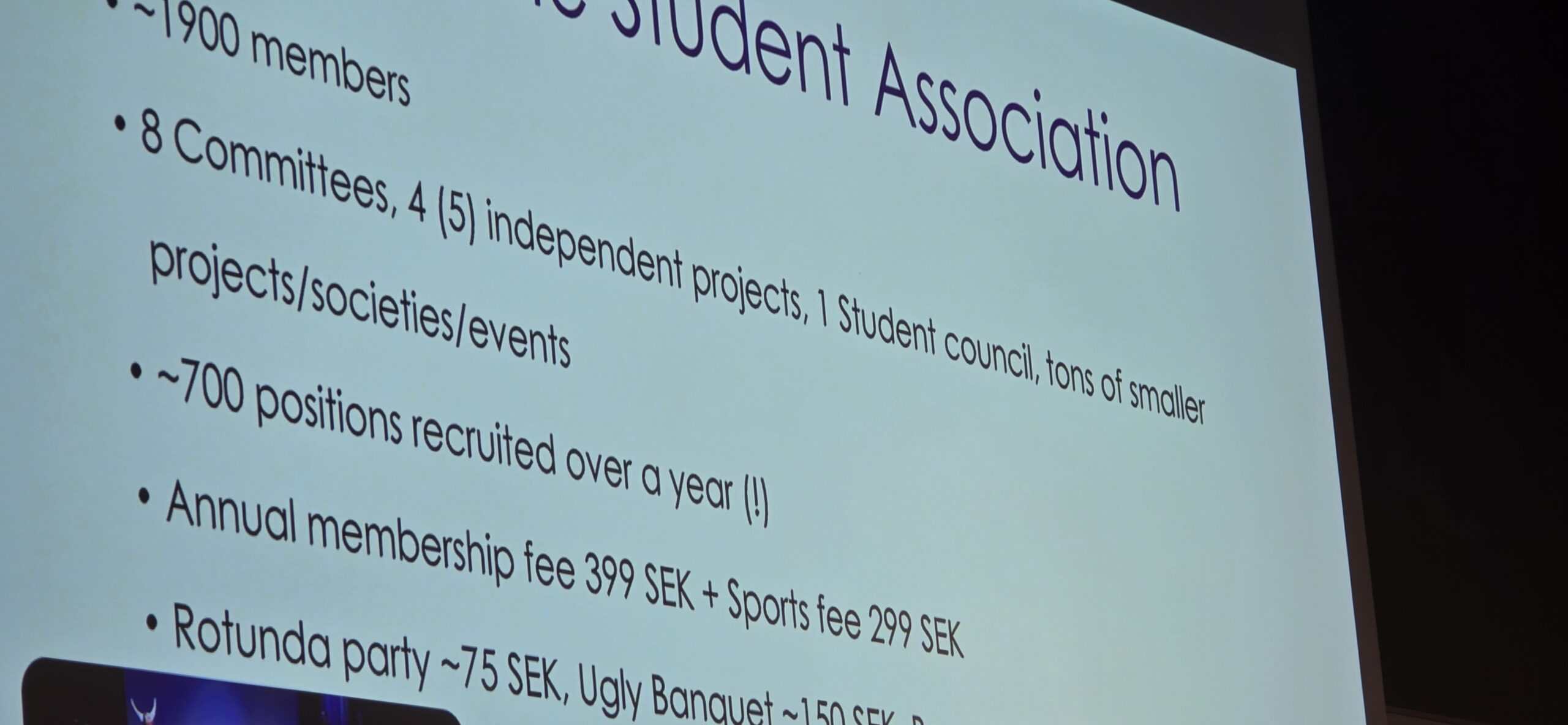

At Stockholm’s School of Economics, the student association’s VP for Education told us that of the circa 1800 students enrolled, about 96 per cent are SU members – and 700 of them are “active”. I think I thought he meant “pitching up to stuff semi-regularly”, but on the next slide he meant ”have a position of responsibility”.

At the KTH Royal Institute of Technology, the volunteers we met from Datasektion – the “chapter” for students studying data science courses – had similar stats, nestled in a much bigger university. We met them in their “chapter room” – something that felt like it was theirs rather than a page from a furniture catalogue. As they presented their slides, I started surfing around their website to count the roles. I soon gave up. There’s even a whole committee for keeping the chapter room clean – it’s their home, after all.

Chatting to the tiny crew of staff at Stockholm University’s SU was a humbling experience. Every time we thought we’d got a grip on their structures, another set unfurled – councils, forums, sports groups, societies, project groups and hundreds of university-level reps shouldn’t be sustainable in a university of 30,000 students – but it is.

Even at Södertörn University just south of the city – a former Högskola (university college) that’s as close as Sweden gets to a post-92, the numbers are wild. There’s reps for departments, reps for subjects, reps for university boards and working groups, reps that run the careers fair, and reps for the SU’s work environment, archives, finance and administration, graphic design, sustainability, communication, project management and student influence and impact.

There’s even 30 odd students that run the pub – without a “grown up” in sight.

It was probably the Doctoral chapter back at KTH that really did it for me. I don’t think it’s unfair to suggest that extracurricular activity and student representation for PhD students in the UK is fairly thin on the ground – in Sweden, not only is there a vision for PGR student life beyond the research and the survival, there are formal time compensation arrangements that support it.

Maybe that’s why there’s branches, projects, EDI initiatives, careers support, international student events, ombudspeople, awards nights, trips, handbooks, student support and highly sophisticated research and lobbying. Actually, maybe that’s why Swedish PhD students are salaried at a level approaching those that supervise them – while our “New Deal” says nothing on student life or representation, and frames stipends equivalent to the minimum wage as an achievement.

There’s many a student leader that’s returned to the UK and decided that they need an elected officer for every faculty, or to create a PGR “officer” or whatever, only to find that the culture in said university or faculty gives that student nothing to work with and little to organise.

One of our new Swedish friends described that as “painting a branch a different colour – the tree will still be brown when the tree grows and the branch falls off”, as she impressively explained the way that students were recruited first to help, then later to take charge, building their confidence and skills along the way.

Causes and effects

Back in the UK, the sector often talks of how students have changed – as if their desires, preferences, activities or attitudes are outside of the gift of educational institutions – something to be marketed to rather than inculcated with.

But every student I’ve ever met wants to fit in – to know the rules of the games, to know how things work around here, to know how to fit in. Maybe how they’re inducted and supported – and who does that induction and support – matters.

Maybe it’s about age – students enrol into higher education later in Sweden. Maybe it’s about pace – in the standard three years, only about 40 per cent of bachelor’s students complete – add on three years, and “drop out” is as low as in the UK.

Maybe it’s about a wider culture of associative activity – the UK always has been useless at sustaining mutuals, and our participation rates in them are near the bottom of the European tables.

Maybe it’s the legislation – law that has given students the formal right to influence their own education and a panoply of associated rights without the tiresome discourse of consumerism or “what do they know” since the 1970s.

Maybe it’s about trust. You soon spot when you visit a country how much its people are trusted when you jump on a train – “it must be because it’s so cheap” is what we tend to think, but maybe that lack of barriers and inspectors is about something else.

Less than 4 in 10 staff in Swedish Universities are non-academic, far less than in the UK. Maybe we do so much for students in the UK because they need the help. Maybe we’ve convinced ourselves – both in universities and SUs – that they can’t or won’t do it on their own – or that if they did, they’d mess it up, or at least mess the metrics or the marketing up.

In that endless search for the secret sauce, the research doesn’t help. In theses like this, the most common reasons for student volunteering in Sweden are improving things/helping people, meeting new people/making friends, developing skills, and gaining work experience/developing their CV. Like they are everywhere.

International students, particularly those studying away from their home country, are more likely to volunteer as a way to make new social connections. Younger students tend to volunteer more frequently than older ones. And universities could encourage volunteering by increasing awareness, linking it to academic subjects, and offering rewards or networking opportunities. We knew that already.

But actually, maybe there’s something we didn’t know:

Swedish students tend to volunteer because it is seen as normal rather than something extraordinary.

And that takes us back to Wisconsin.

Normal for Norfolk

In this terrific podcast, Markus Brauer urges anyone in a university trying to “change the culture” to focus on the evidence. He says that traditional student culture change initiatives lack rigorous evaluation, rely on flawed assumptions, provoke resistance, and raise awareness without changing behaviour.

He critiques approaches that focus on individual attitudes rather than systemic barriers, stressing that context and social norms – not just personal beliefs – shape behaviour. Negative, deficit-based framing alienates. And it’s positive, evidence-based, and systematic strategies – structural reforms, visible institutional commitments and peer modelling that really drive the change.

Maybe that’s why each and every student leader we met had an engagement origin story that was about belonging.

When I asked the International Officer at the Stockholm Student Law Association what would happen if a new student didn’t know how to approach an assignment, he was unequivocal – one of the “Fadder” students running the group social mentoring scheme would do the hard yards on the hidden curriculum.

When I asked the Doctoral President at KTH how she first got involved, it was because someone had asked her to help out. The Education VP at the School of Economics? He went to an event, and figured it would be fun to help run it next time because he’d get to hang out with those that had run it for him. Now he runs a student-led study skills programme and gets alumni involved in helping students to succeed. Maybe it’s that. School plays sell out.

Belonging has become quite important in HE in recent years. The human need to feel connected, valued, and part of something greater than ourselves has correlations with all sorts of things that are good. Belonging shapes students’ identities, impacts their well-being, enables them to take risks and overcome challenges with resilience.

But since we’ve been putting out our research, something bad has been happening. Back in the UK, I keep coming across posters and social media graphics that say to students “you belong here”

And that’s a problem, because something else we know is that when a student doesn’t feel like that and when there’s no scaffolding or investment to stimulate it, it can make students feel worse. Because the other thing we’ve noticed about how others in Europe do it is that it’s about doing things.

Doing belonging

The first aspect of that is that when students work together on something it allows us to value and hope for the success of others beyond their individual concerns. They want the project to succeed. We want the event to go well. They smile for the photos in a group.

The second is that when they work in a group and they connect and contribute they’re suddenly not in competition, and so less likely to lose. When they’re proofing someone’s essay or planning a route for a treasure hunt, they’re not performing for their success – they’re performing for others.

But the third is that they start to see themselves differently. Suddenly they’re not characterised by their characteristics, judged by their accent or ranked by their background. They start to transcend the labels and become the artist, the coach, the consultant or the cook.

The folklore benefits of HE participation are well understood and hugely valuable to society. They’re about health, wellbeing, confidence, community mindedness and a respect for equality and diversity.

In every country in the process of massifying, the debate about whether they’re imbued via the signalling of those that go (rather than those that don’t), or whether they’re imbued via the graduate attributes framework variously crowbarred into modules, or imbued simply via friendship or via the social mixing that seems so scarce in modern HE rages on.

My guess is that it’s partly about having the time to do things – we make student life more and more efficient at our peril. It’s partly about giving things back to students that we’ve pretty much professionalised the belonging out of. It’s partly about scaffolding – finding structures that counterintuitively run against the centralisation rampant in the management of institutions and causing students to organise their communities in groups of the right size.

Maybe it’s all of that, or some of it. Maybe some good social norming videos would help.

But my best guess is not that higher education should show new students a manipulative video tricking them into the social proof that helping others is fun. It’s that seeing other students do things for them – and then asking them to get involved themselves – is both the only way to build belonging and community, and the only way to ensure that the benefits of participation extend beyond the transactional.

When students witness peers actively shaping their environment, supporting each other, and making tangible contributions to their communities, they don’t just internalise the value of participation – they embody it. Creating the conditions where reciprocity feels natural, expected and rewarding is about making it natural, expected, and rewarding.

The more HE massifies, the more the questions will come over the individual benefits to salary, the more the pressure will come on outcomes, and the more that some will see skills as something that’s cheaper to do outside of the sector than in it.

If mass HE is to survive, its signature contribution in an ever-more divided world ought to be belonging, community and social cohesion. However hard it looks, that will mean weaning off engineering individual engagement from the top down – and starting to enable community engagement from the ground up.