The final months of a PhD are pretty terrifying at the best of times. The search for a job, either inside or outside of academia, goes on alongside countless rewrites and revisions.

But, for many on the final stretch of this struggle, the constantly shifting political landscape and the nature of whatever form the UK’s exit from the European Union takes adds an unwelcome complication.

An apt topic

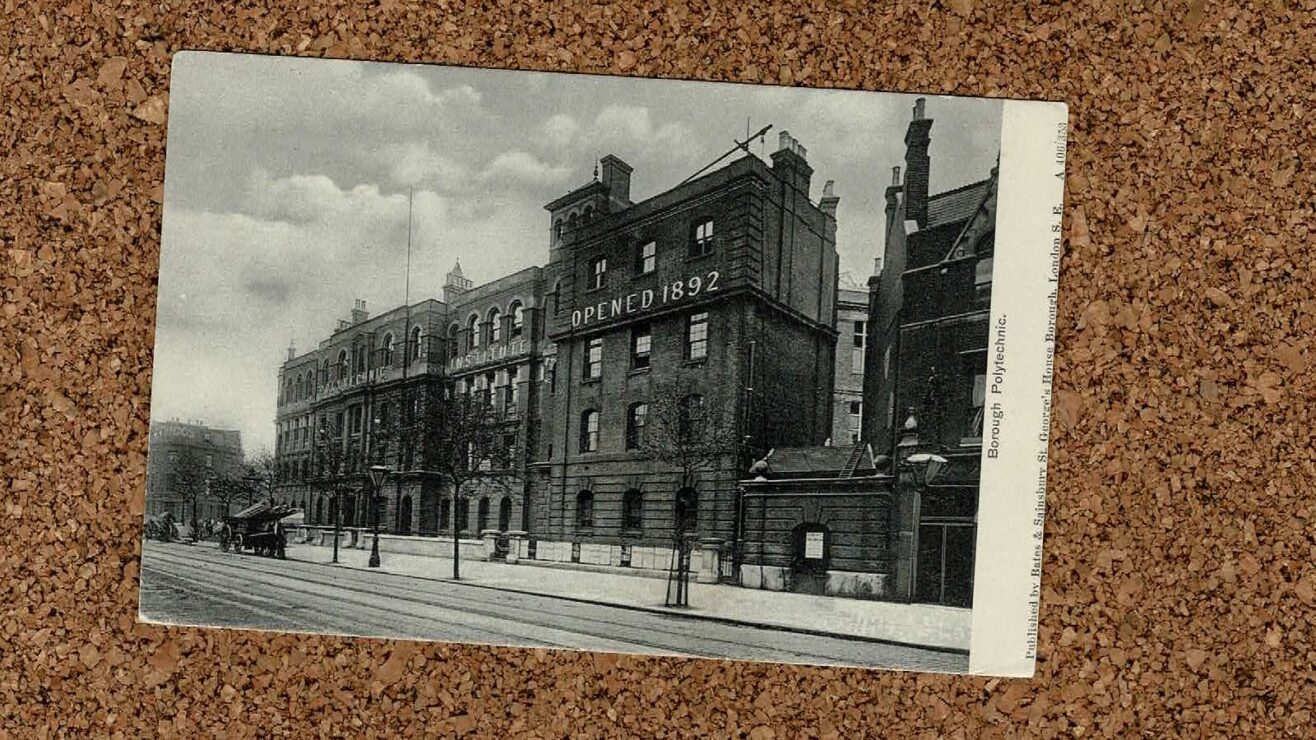

Alexandra Bulat is in the last stages of writing up her PhD at UCL, on attitudes towards EU migrants in the context of Brexit. She holds UK settled status, and an MPhil from Cambridge. She is also the project manager of the citizen-led engagement programme for young Europeans at campaign group the3million. Her work and her research have led her into conversations with many who are uneasy about the growing likelihood of a no deal Brexit.

The3millon works with a partner charity, Settled, which receives some funding from the Home Office to support their work with EU citizens in precarious circumstances in the UK. In contrast, students and staff have backing from their university or college, who – in the main – have offered a wide range of support and advice. She told me:

Larger universities offer a lot of support for EU citizens, because they are interested in retaining their staff. But there is a lot of concern that more academics will choose to leave the UK even if they are successful in securing settled status

The practicalities of getting to settled status can be problematic, with the blithe reassurances of simplicity from the Home Office at best unhelpful. The Advertising Standards Agency recently took issue with the claim you only needed your passport or ID card – in reality most people, who may not have enough data on HMRC and DWP databases linked to their National Insurance number, needed more than this, including Alexandra. She was asked for documentation for each year of residence in the UK.

I first applied under the EEA permanent residency system and was rejected. For settled status I was able to get documentation from the universities I studied at. It was not as simple and straightforward as the Home Office portray it – and I have fluent English and was fully supported. But getting such documentation from universities is comparatively easy.

The infamous Home Office app still only runs on certain Android phones – and there are still systemic issues. Most notably the ID check app was supposedly “under maintenance” for several hours after Priti Patel’s recent announcement ending freedom of movement.

Supporting the academics of the future

Although the information and support is out there, it is not clear that it is reaching students – who may not choose to read a “Brexit newsletter” or similar. One recent conversation revealed that some felt that their student status meant that they did not have to apply for settled status.

Doctoral students are our academics of the future – and adding the uncertainty of Brexit to the usual uncertainty is making jobs elsewhere in the world look far more appealing. It isn’t just Brexit – it’s salary too. By international standards UK postdocs are paid little and have huge living costs, especially in London. Add in an increasingly hostile environment and you can understand why even someone with indefinite leave to remain would wonder about opportunities in other parts of the world.

And don’t think those who study or work overseas will return. Settled status allows for five years outside the UK – after which point the UK’s immigration rules apply. So a UK master’s student who is an EU citizen with settled status may be offered a PhD at Harvard, but would find it hard to return to the UK to work. Likewise a newly-minted PhD who does post-doctoral work in Bologna and Uppsala.

Those on funded PhDs have a further worry – does their funding come from an EU supported project? Will the UK need to rationalise and redistribute its own research funding to replace what is missing?

And – even worse – Priti Patel’s announcement that free movement would end on 31 October despite earlier assurances to the contrary creates the prospect of an uncomfortable gap. EU citizens have until 31 December 2020 to apply for settled status, but after 31 October this year there is no way of distinguishing on a practical basis between those who entered the UK under free movement and have yet to receive (or apply for) settled status and those who move to the UK (potentially illegally) after 31 October. Though Patel has now been forced to roll back on her plans, the lack of certainty over any transition period remains. There is a very real chance that overzealous implementation will lead to another Windrush.

Campaigning for clarity

In rapidly upgrading no deal from a distant possibility to an increasingly plausible scenario Boris Johnson’s government has left many with the impression that it is the most likely outcome. Alexandra told me:

Things have become a lot more uncertain. Suspending parliament and pushing a no-deal Brexit through feels like the very worst option. An agreement to secure our status internationally – the ring-fencing what has been agreed already during the UK-EU negotiations – feels more unlikely

Theresa May’s withdrawal agreement included text securing the rights of EU citizens in the UK, and UK citizens in the EU. Even here, the UK’s approach has tended toward the more restrictive of the two allowable process options – choosing an application system (with the onus on EU citizens to prove their right to remain) rather than a declaratory system (where those already living in the UK are presumed to have the right to remain unless it was proven otherwise).

Promises from the Government are now much less believable. Alexandra noted that the initial promise in 2016 was that the status of EU nationals would not change and that they would be given indefinite leave to remain ‘automatically’. There was no mention of having to apply for the right to remain.

The3million are campaigning for clarity and simplification, and for a switch to a declaratory system to avoid people missing out. But there’s even a need for something as basic as physical documentation as a simple way to prove your status – there’s little trust in a digital system that offers an additional barrier in finding a job or a home.

Boris Johnson chose to make research a central point of his first Facebook chat with the nation, but there was little in there to like for the next generation of academics who are increasingly seeing a more welcoming future elsewhere.