One of the most alarming things about the Department for Education (DfE) commissioned National review of higher education student suicide deaths is the apparant role of academic pressure.

Well over a third of the serious incidents reviewed made explicit reference to academic problems or pressures – often tied to exams or exam results.

Other pressures included anxiety about falling behind, upcoming deadlines, perceived pressure to perform, and involvement in “support to study” procedures.

And just under a third of those reviewed had submitted requests for mitigating circumstances – often citing personal reasons, mental health issues, or anxiety about academic performance.

The review concluded that students struggling academically should be recognised as at-risk and provided with enhanced, compassionate support – and noted the need for greater awareness at critical points in the academic calendar, particularly around exam times, given that March and May saw peaks in suicide and self-harm incidents.

Basically, academic pressure was not a sole cause but a consistent co-factor – frequently present and potentially exacerbating existing vulnerabilities. The report calls for better early detection, more proactive outreach, and a systemic rethink of how institutions respond to academic distress before it becomes a crisis.

But what if the system, and its associated rhythms and traditions, is itself causing the problems?

See the mess and trouble in your brain

In our recent polling on health, academic culture emerged as a significant but often overlooked determinant, with students describing patterns of overwork, presenteeism, and what we’ve heard called a “meritocracy of difficulty” in some countries – one that rewards suffering over learning outcomes.

My department seems to pride itself on how much we struggle,” wrote one student, while another observed that “lecturers brag about how little sleep they get, as if that’s something to aspire to.” In some departments in some providers, unhealthy work patterns are normalised and even celebrated.

Assessment strategies featured prominently in student concerns about academic pressure. “Having five deadlines in the same week isn’t challenging me intellectually – it’s just testing my ability to function without sleep” and “I’ve had to skip meals to finish assignments that seem designed to break us rather than teach us” are two of the comments that got the highlighter treatment.

Some spoke of the way in which assessment approaches particularly disadvantage students with health conditions:

When everything depends on one exam, my anxiety disorder means I can’t demonstrate what I actually know.

The glorification of struggle appears deeply embedded in some disciplines. “There’s this unspoken belief that if you’re not miserable, you’re not doing it right,” noted one respondent. Another observed:

…completing work while physically ill is treated as a badge of honor rather than a sign that something’s wrong with the system.

Students also highlighted the disconnect between health messaging and academic expectations – “The university sends emails about wellbeing while setting impossible workloads” and “We’re told to practice self-care but penalised if we prioritise health over deadlines.”

Many articulated a vision for healthier academic cultures – with comments like “Learning should be challenging but not damaging,” and “I want to be pushed intellectually without being pushed to burnout.” As one student noted:

The university keeps trying to teach us resilience when what we really need is a system that doesn’t require being superhuman just to graduate.

Students called for workload mapping across programmes to identify assessment bottlenecks and unreasonable clustering, alongside assessment strategies that offer more flexibility and multiple ways to demonstrate learning.

They advocated for mandatory staff training on setting healthy work boundaries and avoiding “struggle” glorification, as well as health and wellbeing impact assessments for all new curriculum and assessment designs.

Their asks included “reasonable adjustments by design” policies ensuring assessments are accessible by default, clear policies distinguishing between challenging academic content and unnecessary stress, and the revision of attendance policies to discourage presenteeism during illness.

One comment pushed for student workload panels with the authority to flag unsustainable academic demands. As the respondent put it: “If workload is such an issue for UCU, why isn’t an issue for the SU”?

You feel lazy but stop the fantasies and bubble butts

Even when we were in the EU, the UK for some reason always declined to take part in Eurostudent – a long-running cross-national research project that collects and compares data on the social and economic conditions of higher education students in Europe.

But we can do some contemporary comparisons.

First we can look at the World Health Organisation’s Well-Being index (WHO-5), which invites respondents to consider whether, over the past two weeks:

- They have felt cheerful and in good spirit

- They have felt calm and relaxed

- They have felt active and vigorous

- They woke up feeling fresh and rested

- Their daily life has been filled with things that interest me

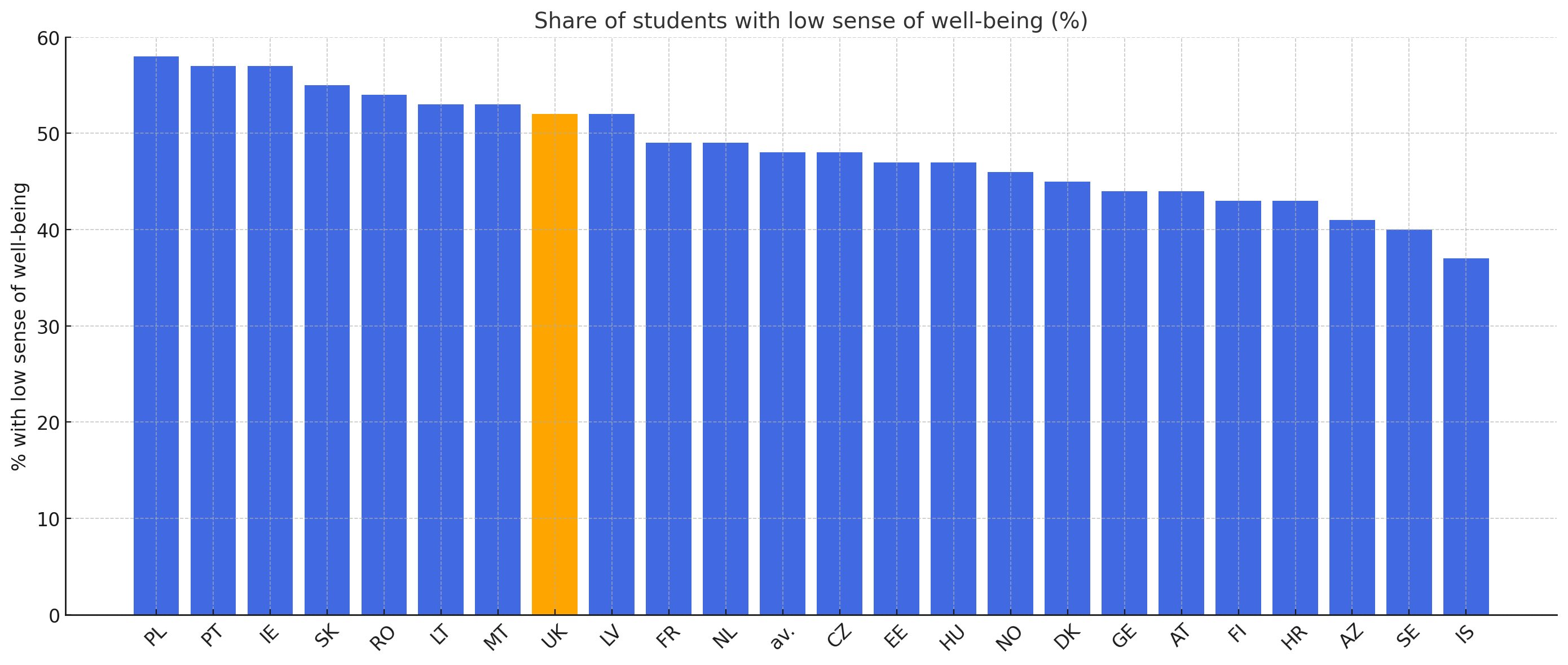

Cibyl’s Mental Health Research is the largest UK study of university students and recent graduates’ mental health – and if we consider its results via the Eurostudent comparison, we are at the upper end of low well-being.

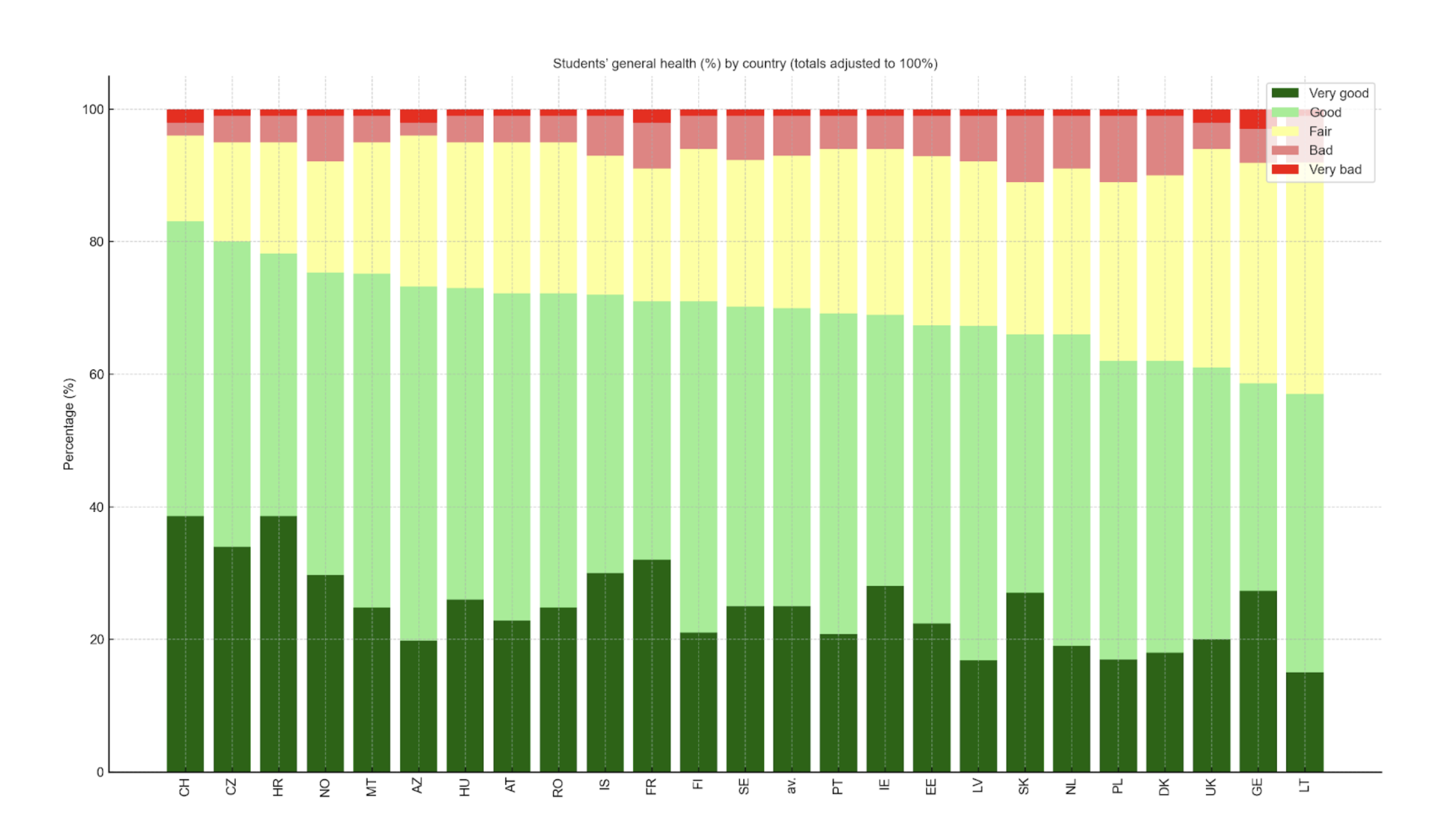

We can also look at students’ general perceptions of their own health – a big part of which will be their mental health – where we’re third from bottom:

The question asked in Eurostudent is the one we asked in our recent health polling. If we sort by the percentage of students responding positively, we don’t fare well – and the temptation would be to assume that if we can act to improve students’ health, we might ease academic pressures.

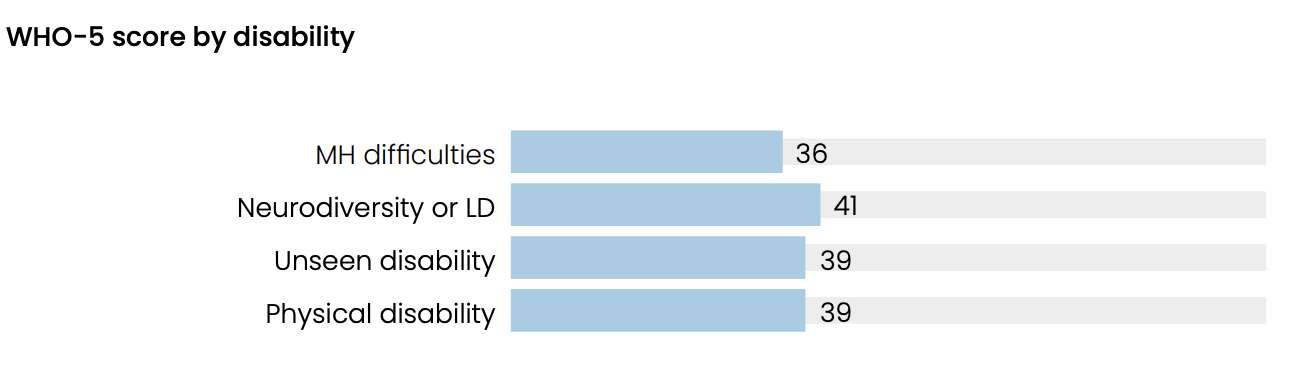

Students are diverse, of course. Here’s what our scores look like by disability:

The mind drifts to improvements to the NHS, increased awareness, cheaper and more nutritious food or easier access to sports facilities. But as we know, causation is not correlation. What if, rather than good health being a solution to academic pressure, that pressure is a cause of the bad health?

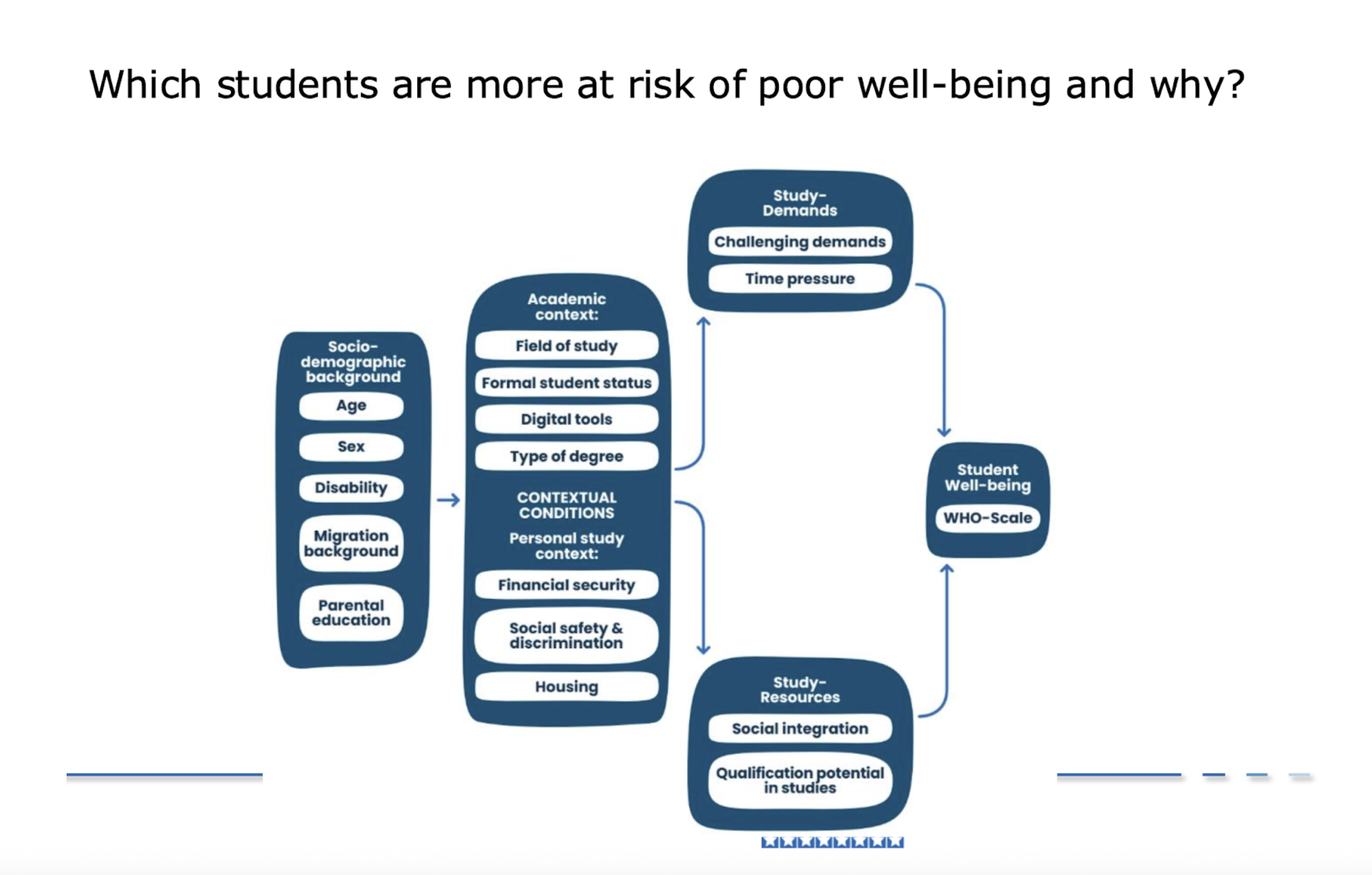

In this detailed Eurostudent 2024 analysis, higher study demands – specifically long hours spent on coursework, preparation, and class attendance – were directly associated with lower wellbeing scores.

The findings are grounded in a Study Demands-Resources (SD-R) framework, which distinguishes between stress-inducing demands (like excessive workload or time pressure) and supportive resources (such as peer contact or teacher guidance).

In multivariate regression analyses, students who reported the highest time spent studying were consistently more likely to report poor well-being, defined by WHO-5 scores of ≤50. The trend held even after controlling for social and financial variables.

Students studying more than 40 hours per week consistently reported lower wellbeing scores, while those studying 30-40 hours show optimal outcomes. Interestingly, students studying under 20 hours also experienced reduced wellbeing, likely reflecting disengagement or underlying difficulties rather than lighter workloads being beneficial.

Commuting time created additional strain, with wellbeing decreasing progressively as travel time increases – students commuting over 60 minutes each way showed notably lower scores than those with shorter journeys.

The relationship between paid work and wellbeing followed a pattern where moderate employment (1-20 hours weekly) actually enhanced student well-being, possibly through increased financial security or beneficial structure. But working more than 20 hours weekly eroded those benefits and became detrimental to mental health.

Childcare responsibilities initially appeared to correlate with slightly higher wellbeing, but the effect disappeared when support systems were factored in – suggesting external support rather than the caring role itself influenced outcomes.

Excessive academic pressure drained cognitive and emotional reserves. Without adequate recovery, connection, or flexibility, students began to internalise stress, which eroded their self-efficacy and increased the risk of burnout, depression, and anxiety. As students fall behind, the pressure compounds – creating a feedback loop of academic struggle and psychological deterioration.

Running from the debt in the battle of cyber heads

Intertestingly, age played a crucial role – older students tended to report higher levels of well-being compared to younger students. This was attributed to more effective coping strategies such as increased support-seeking and greater use of engagement strategies, while younger students are more likely to use avoidance strategies.

EUROSTUDENT’s model explicitly included age as a socio-demographic factor that shaped a student’s “contextual conditions” – such as their academic and personal study environments – which in turn influenced study demands, access to resources, and ultimately mental health outcomes.

Its multivariate analysis supported the idea that age has a statistically significant impact on wellbeing, even when controlling for other factors such as financial stress and social isolation. All of which puts two key stats into sharp focus.

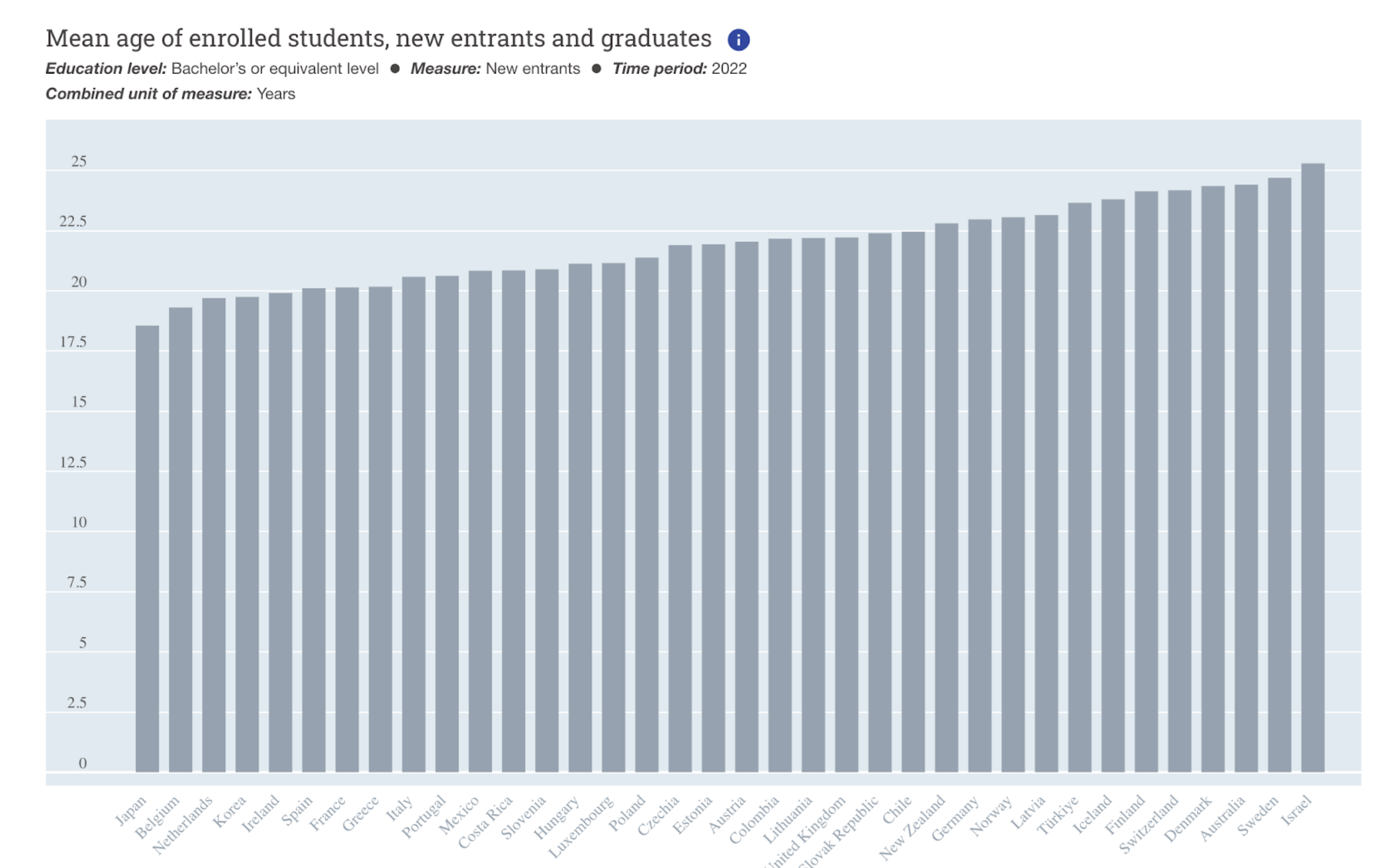

Our undergraduates are pretty young – In Europe only Belgium, Greece and the Netherlands beat us on percentage of 18/19 year olds enrolled, and here’s the mean age of undergraduates on entry across the whole OECD. We’re in the middle of the pack on 22:

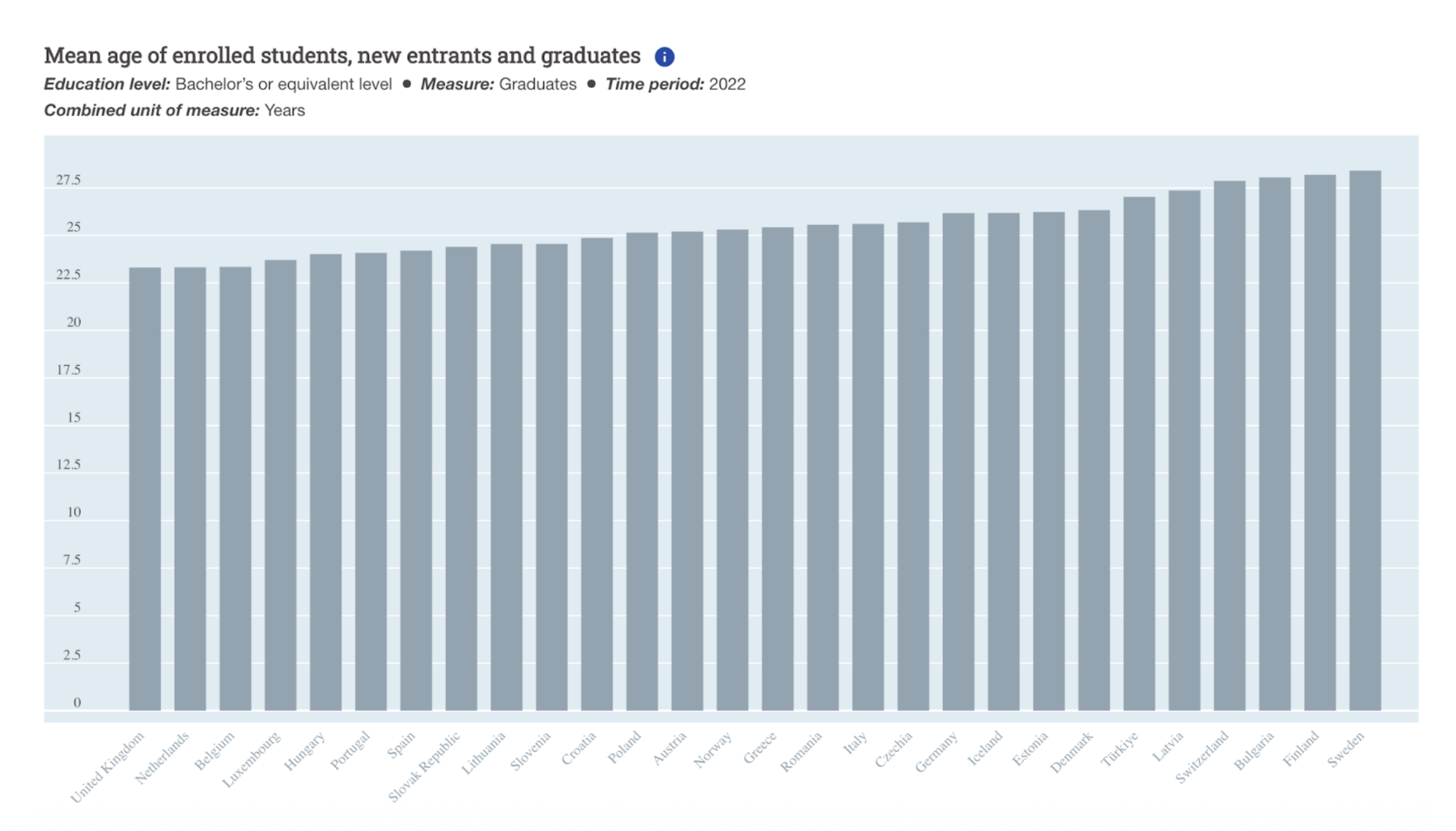

But here’s the distribution for the average age on graduation from a Bachelor’s, which suggests we have the youngest undergraduate graduates in Europe:

If you then bear in mind that our non-completition rates are lower, it’s hard to avoid coming to the conclusion that at least part of the problem we see with wellbeing and mental health is structural – and that taking steps to cause students to both enrol later, and complete slower, would help.

Keep you feeling impressed

In recent years, plenty of other countries have been attempting to speed up their students’ completion – partly because those countries are keen to get often older students out into the labour market.

But it does mean that the research that has gone into why students take so long in some countries to accrue the 180 credits for a Bachelor’s can be interrogated for signs of those systems’ ability to accommodate and relieve pressure.

A decade ago, the HEDOCE (Higher Education Dropout and Completion in Europe) project was a large-scale comparative study examining dropout and completion rates across 35 European countries – providing insight into the policies that European countries and higher education institutions employed to explicitly address study success, how these policies were being monitored and whether they were effective.

It combined a literature review of academic and policy documents with three rounds of surveys among selected national experts from each country, eight in-depth country case studies (Czech Republic, England, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway and Poland), institutional case studies within those countries including interviews with policy-makers, institutional leaders, academic staff and students, and statistical analysis of available completion, retention and time-to-degree data.

It found Denmark providing student funding in a way that explicitly acknowledged that the theoretical three-year timeline may not reflect educational reality. The Netherlands went further, offering students a full decade after first enrolment to complete their degree for loan-to-grant conversion, a policy that helped reduce average time-to-degree from 6.5 to 5.8 years while improving completion rates.

It’s notable that the populists’ proposal of a study-time penalty to reduce the time further late last year in NL brought swift condemnation from the two national students’ unions – with concerns that forcing the same pace would result in unequal outcomes, worries that students’ high employment-during-studies rates were incompatible with a faster pace for some, and a major concern that the tens of thousands of students attempting less than 30 credits in a semester to fit in a “Board semester” – running the country’s impressive array of student associations – would be under major threat.

In the HEDOCE report, researchers talk about “pressure reduction” – when students know they have more than three years available, “each individual semester failure is less catastrophic” and systems can “focus on mastery rather than speed.” Students facing temporary setbacks – health issues, family circumstances, financial pressures – were able to reduce their course load temporarily and extend overall duration rather than dropping out entirely.

Students became “less likely to drop out entirely when facing academic difficulties” and “more likely to persist through temporary setbacks.”

The Norwegian experience illustrates. Despite – or perhaps because of – allowing extended completion periods, at the time Norway was maintaining completion rates of 71.5 per cent at bachelor level and 67 per cent at master’s level. Students could “explore additional courses and find their optimal path without penalty,” with the well-functioning labour market reducing urgency to complete quickly as “employment opportunities exist even without completion.”

Extended duration systems acknowledged the reality of student employment. The study found that students working more than 20-25 hours per week in Estonia and Norway showed higher dropout risk – but the systems accommodated it rather than penalising it.

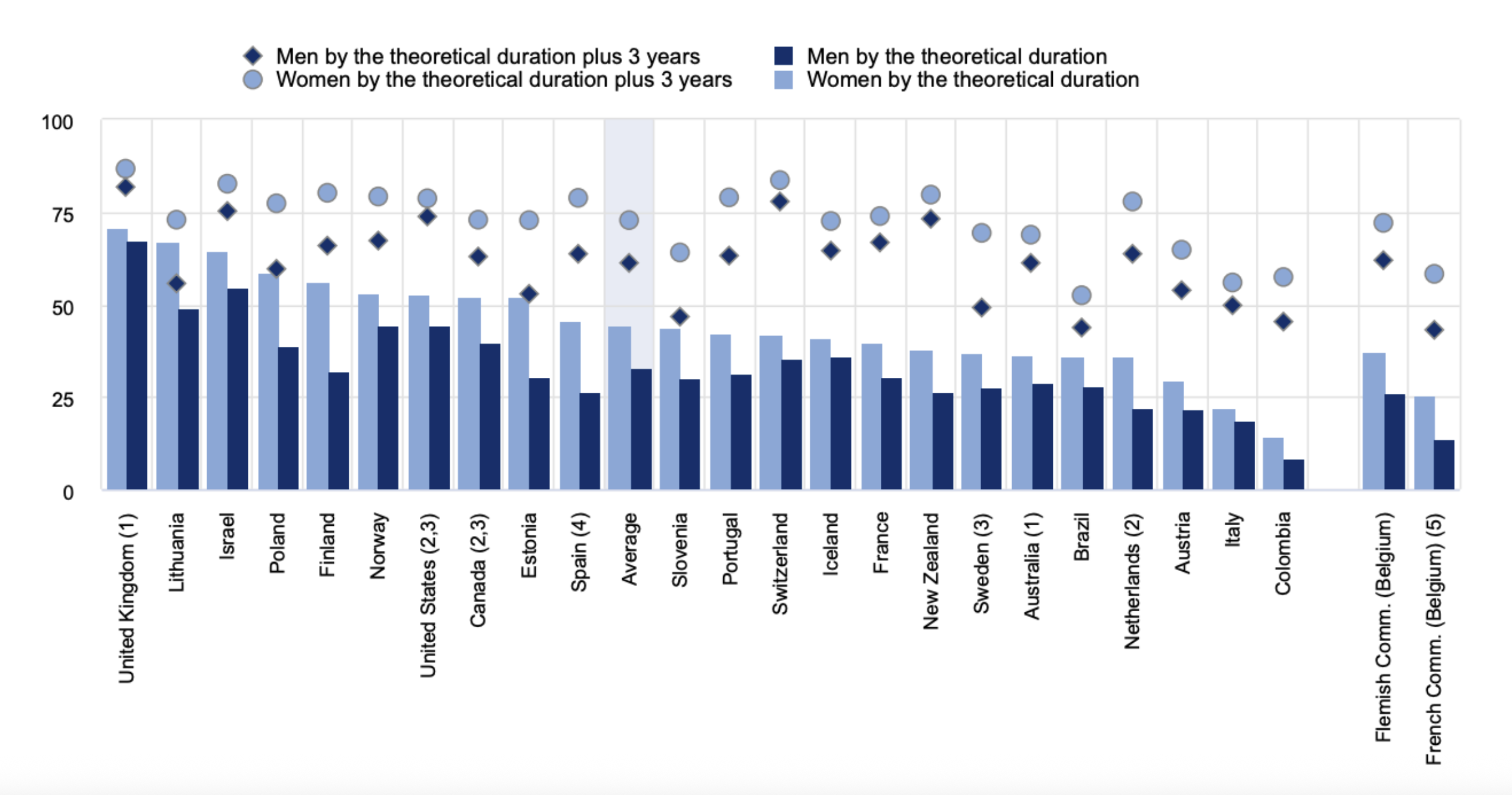

These systems also enabled what the report termed “assessment flexibility and academic readiness.” Students were able to gauge their preparation for examinations, retake failed modules without catastrophic consequences, and accumulate credits over multiple attempts rather than facing binary pass-fail decisions with immediate ejection consequences.

Germany’s continuous assessment systems exemplified the approach – allowing students to “gauge their readiness” for progression rather than facing predetermined examination schedules regardless of preparation level. Ditto the Netherlands’ Binding Study Advice system – where students received intensive counselling and multiple opportunities for course correction, with the safety net of extended completion timeframes preventing premature dropout due to temporary academic difficulties.

It’s also worth noting that countries prioritising completion over speed consistently showed better outcomes. Many European systems were:

…explicitly designed to prioritise completion over speed, viewing extended duration as preferable to dropout.

That challenges fundamental assumptions about educational efficiency. If the goal is maximising human capital development and minimising wasted educational investment, then systems that achieve 80 per cent completion over four to five years may be superior to those achieving 60 per cent completion over three years.

As such, the evidence suggested that policymakers face a genuine trade-off between completion speed and completion rates. Systems optimised for rapid completion – three years maximum, immediate financial penalties for delays – may have achieved faster average graduation times but at the cost of overall completion rates.

So what are we to make of the UK’s stats – where we seem to manage to combine a lower study hours-per-ECTS credit with lower drop-out rates than average and faster enrolment-to-graduation times?

Every day we live a miracle

Rather than extending duration to reduce pressure, the report argued that the UK system maintained “a fairly tight admissions system” combined with:

…a widespread and embedded expectation that completion is possible in three years except for exceptional circumstances.

Students and families “do not expect to study for longer than the normal time period,” creating social and cultural momentum toward timely completion, and England’s 2012 funding reforms – shifting to £9,000 annual tuition fees with income-contingent loans – created what the researchers describe as putting “students in the driver’s seat.”

It seems to suggest that the market-driven approach and a desire to avoid extra debt was generating different behavioural incentives than the extended-support models elsewhere.

Higher education institutions became “dependent on students and study success for their funding,” creating institutional incentives for retention without requiring extended timeframes. It also noted that in England, the HEFCE Student Premium provided targeted funding for institutions enrolling students “with a higher risk of dropout,” but that that operated within the three-year framework rather than extending it.

Most significantly, it identified the English approach as creating what might be termed “compressed intensity” rather than “extended accommodation” – noting that “institutions and students are not funded for more than three plus one years (except for longer courses),” creating hard financial boundaries that concentrate educational effort.

Everyone else in Europe might be scratching their head – England in particular seems to challenge the general finding that extended duration typically improves completion rates.

It suggests an alternative model – intensive, time-bounded education with high support levels and clear completion expectations may achieve similar or superior outcomes to extended-duration systems. But at what cost?

You don’t need an upgrade anymore

The pressures identified in the HEDOCE report have intensified since its publication a decade ago. England’s “tight admissions system” referenced in the research is considerably less tight now as we continue to widen access, yet the temporal constraints remain unchanged. That creates a fundamental mismatch between institutional capacity to support diverse student needs and the rigid three-year framework within which everyone expects them to operate.

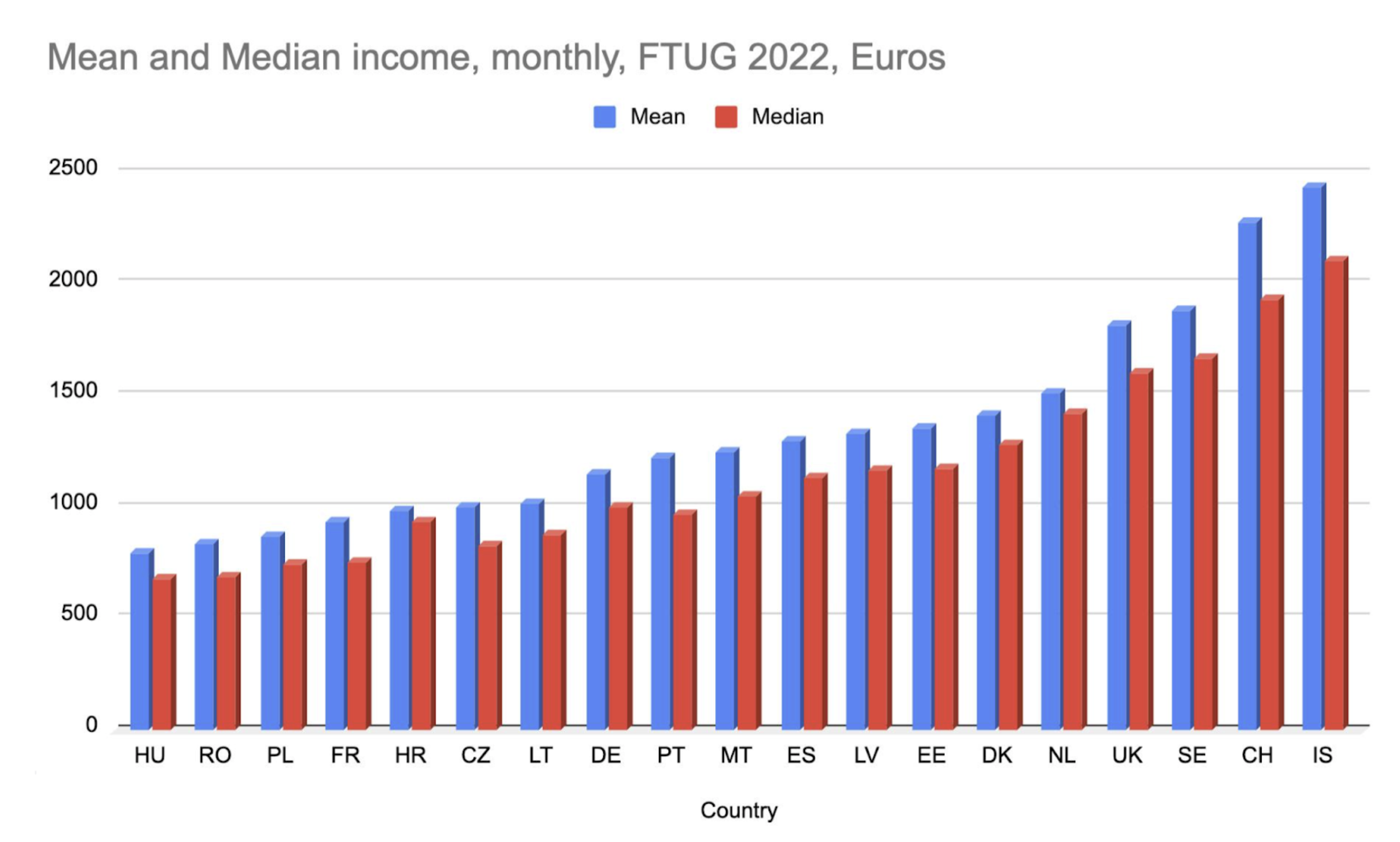

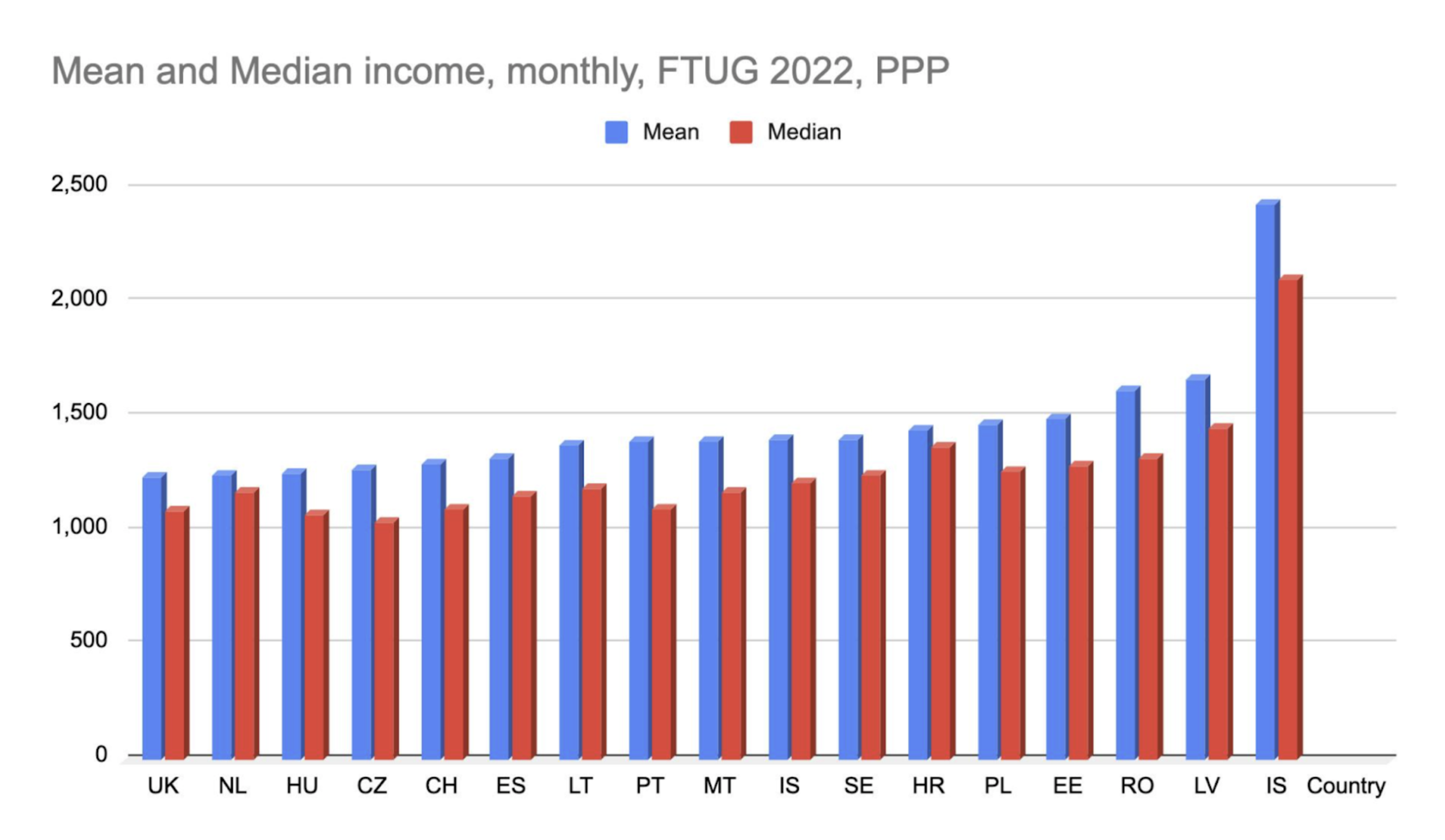

The student premium funding available today is nothing like as helpful as it was a decade ago, EUROSTUDENT’s model is as vivid as any on the interactions between student financial support, and any regular reader of Wonkhe will know how far that has fallen in comparison to costs on all sorts of measures. Here’s how we look on average student incomes:

And here’s how we look when we adjust for comparative spending power:

Maybe our comparative wellbeing data looks worse precisely because we’ve created a system that prioritises throughput over student experience. Our high percentage of students living away from home, combined with annual rental contracts and significant financial commitments, makes dropping out extraordinarily difficult even when it might be the healthiest option. Students facing mental health crises may persist not because they’re thriving, but because the economic and social costs of withdrawal are so prohibitive.

Our student maintenance systems don’t really allow enrolling into less than 60 credits a year even if a student wanted or needed to – and the regulatory pressures in the UK, especially England, to reduce dropout rates has created incentives to push students through.

Rather than addressing the underlying causes of student distress, institutions focus on retention metrics that may keep struggling students enrolled but not necessarily supported. A “retention at all costs” mentality may well contribute to the compressed intensity that characterises the system.

No more nap, your turn is coming up

The temporal aspects are especially telling. Even if you set aside the manifest unfairness of a system whose most popular assessment accommodation for disabled students is “extra time”, it causes chaos – and deep opposition when things like self-certification is clawed back at the altar of “academic standards” that seem to be about pace rather than attainment.

Then the high costs of student support services coping with the race mean that early intervention – the kind identified as crucial in the suicide review – often come too late or prove inadequate. When institutions are financially incentivised to maintain high completion rates within tight timeframes, the investment required for genuine wellbeing support becomes a secondary consideration.

When Denmark had a run at speeding students up, this study found that the majority of students were led by an explorative educational interest that contradicted the reform’s demand that all students complete their education at the same pace. It also found a need to consider wider social interest and engagement among students:

Rather than focusing exclusively on their own success, the students in the survey were often motivated by the social aspects of the study environment, and in many cases, the study environment appeared crucial for the students’ motivation and their completion times.

In one telling quote, a first-year student in Computer Science saw the reforms as a risk to students’ voluntary engagement:

One of the places where I think the Study Progress Reform will shoot itself in the foot is that there will no longer be someone who has the time to be a student instructor, because you have to complete your study in half the time. There is nobody who dares to sacrifice their own studies in order to teach others about what they learned last year.

Another explained how she might take advantage of the new rules on transferring ECTS credits to gain more time for her bachelor project:

I have perhaps become a bit rebellious in relation to the new regulations because I would like to enjoy this study… I would like to have more time to go into greater depth. I cannot plan what will happen in ten years, and I cannot see how the job market will look, but at the same time, I just simply need to look forward. … I have decided what I will write about in my bachelor [project], and I could actually use some of those credits from Tibetology, which I studied before.

A third thought the reform had made her reconsider her own propensity to risk:

It has always been important for me to have a period of study abroad, and it was an essential objective to learn and speak a decent level of Spanish. But then I found out the other day that the study abroad agreement that the Ethnology Department has in Spain requires that you take an exam in Spanish. And you have to take a language test before you go down there. … I think that now, all of a sudden, there is a lot at stake.

The paper concludes that an acceleration of time has taken place in late capitalist societies, with movement becoming an objective in itself – institutions and practices are marked by the “shrinking of the present”, a decreasing time period during which expectations based on past experience reliably match the future.

Can’t you see the link?

But there’s another dimension to the story that complicates any simple narrative about slowing down or extending duration. The evidence from international skills assessments suggests that our efficient degree production system isn’t actually producing the learning outcomes we might expect.

The Mincer equation – the fundamental formula in labour economics that models the relationship between earnings, years of schooling, and work experience – has traditionally suggested that each additional year of education participation yields measurable increases in both skills and earning potential. So what does the UK’s speed mean for learning and earning?

The 2023 PIAAC (Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies) results reveal that UK graduates, particularly those from England, perform relatively poorly compared to graduates in many other OECD countries across literacy, numeracy, and adaptive problem-solving assessments.

The scale of the underperformance is stark. Adults in Finland with only upper secondary education scored higher in literacy than tertiary-educated adults in 19 out of 31 participating countries and economies, including England. While England has seen a 13 percentage point increase in the proportion of tertiary-educated adults between 2012 and 2023, average skills proficiency has not increased correspondingly. The PIAAC data show no significant gains in literacy or numeracy among our growing graduate population.

In other words, we’re “producing” graduates faster and more efficiently than most other systems, but they’re demonstrating lower levels of the foundational competencies that their qualifications should represent. UK tertiary-educated adults scored around 280 points in numeracy compared to over 300 in Japan and Finland. In problem-solving in technology-rich environments, only about 37 per cent of UK tertiary-educated adults reached the top performance tiers, compared to over 50 per cent in countries like the Netherlands and Norway.

That suggests that our model of “compressed intensity” may be producing credentials rather than capabilities. The three-year norm, rigid subject specialisation, grade inflation and high completion expectations all appear to prioritise the award of qualifications over the mastery of skills.

The implications are profound. If degrees are not effectively developing human capital – the literacy, numeracy, and problem-solving capabilities that employers, society and students themselves expect – then the entire economic justification for higher education expansion with its considerable personal investment comes into question.

Countries with extended-duration systems may achieve better learning outcomes precisely because they allow time for deeper engagement with material, multiple attempts at mastery, and the kind of reflective learning that develops transferable skills.

The pressure-reduction mechanisms identified in HEDOCE – the ability to retake modules, explore additional courses, and gauge readiness for progression – may be essential not just for wellbeing, but for genuine learning and subsequent economic activity too.

Pressure rocks you like a hurricane

The irony is that students are desperate to slow down. A growing “slow living” movement represents a cultural shift from “hustle culture” to prioritising rest and mental health, driven by widespread burnout and exhaustion.

Books like Emma Gannon’s “A Year of Nothing” and Jenny Odell’s “How to Do Nothing” advocate for intentional rest and resistance to productivity-obsessed capitalism, particularly resonating with those who’ve experienced chronic burnout from economic instability and social pressure to constantly achieve.

Easing off won’t be straightforward. Financial pressures in providers seem to be reducing the optionality of slow(er) credit accrual, as more modules become “core modules” and our rigid system of year-groups gets more, rather than less, entrenched.

Big decisions need to be taken soon re the Lifelong Learning Entitlement. I’ve written before about the way in which universally setting the full-time student maintenance threshold at 60 credits a year is both unreasonable and discriminatory – but even if that was eased off at, say, 45 credits, students will be acutely aware that every extra semester means more cost.

In an ideal world, we’d kill off fees altogether – but even without free education, the case for linking fees to module credit is seriously undermined by the evidence. Why on earth should a disabled student whose DSA has taken all year to come through be expected to pay for another year’s participation while they attempt to catch up?

There’s very little that’s fair about a system where some providers’ students need more support to succeed, but don’t get it because they’re sharing support subsidy with more that need it. Especially when much of that support is needlessly aimed at an artificial time pressure coupled with a low drop-out pressure.

Take the pill to feel the thrill and touch it all

With central government support in DfE budgets under pressure, there’s no chance of student premium funding stepping in to deliver the top-ups required any more.

So link maintenance debt to time in study if we have to – but retain (and rebuild) a progressive repayment system that extracts a fair(er) contribution from those that didn’t need the support (interest on loans), all while severing the link between modular student debt and modular institutional income.

Put another way, if student A needs to take 2 years to get to 180, student B takes 3 years, and student C takes 5 years, if we must have notional (tuition) student debt, they of course should all graduate with the same amount.

Other options are available, and all have trade-offs. But whatever we do, we mustn’t go into the next decade assuming that the system we have created is some sort of miracle, or somehow advantageous in comparison to our international peers.

Our traditions, pace, structures and incentives have all created a dangerous combination of pace and pressure that is damaging students’ real educational attainment and their health. It’s causing harm, and it needs to change.

Completion rates being what they are challenges the thesis of this analysis of ‘structural’ factors related to academic culture that are the significant factor for worsening student mental health. That, and the resolutely biased analysis – where being in the middle of the spectrum, as the U.K. often appears to be in the provided plots – is presented as ‘lower (middle) end’, etc., contributed to a tendencious and I’d argue, lazy, consideration of the data. If you’re making spurious assertions of pressures on students by academic culture, at least bother to provide some cross-cultural analysis against the very data you… Read more »

I despair sometimes. Completion rates don’t disprove structural harm – high completion rates in a pressurised system may reflect students enduring damage rather than thriving. I explicitly note that “retention at all costs” mentality keeps struggling students enrolled but not necessarily supported, while economic barriers make dropping out prohibitively expensive even when it might be healthier. The “middle of spectrum” claim misreads the data – the UK consistently appears at the problematic end across multiple wellbeing measures. Being “middle” on undergraduate age but having the youngest graduates in Europe while showing poor wellbeing outcomes isn’t neutral positioning, it’s a red… Read more »

For me, a significant factor is the compression of the academic year. When I was an undergraduate, we had three teaching terms, each of which was 10 weeks long. I was able to financially support myself by working 16-20 hours per week, and assessments were more evenly spread out. Now the same institution is down to two teaching terms, each only 11 weeks long. This leaves little room for skills development or meaningful engagement with new ideas. Some modules set midterm assessments, but most still use high stakes, heavily weighted and long end-of -module assessments, all of which are due… Read more »

Great article, thanks Jim. I particularly agree with a focus on mastery rather than speed. The neurodiversity in my family means I’ve really learned to appreciate this — very grateful to the wise and very experienced tutor who said the most important thing was that my son ‘take his time’ in his education. It was liberating and the best advice ever.

We try very hard to spread out assessments, but if there are, say, 10 optional modules of which students 5, it’s inevitable that some module combinations will have assessments in the same week. There are only 11 weeks in the semester and modules have to have 2+ points of assessment. Taking longer to graduate is an interesting one. We very often encourage students to take a break. Spend a year working or recovering, and come back when you’re in a better place to focus on studies. The resistance typically comes from the students themselves (possibly parents too?) who want to… Read more »

I think there might be an interesting direction here but the hard data needs narrowing down a bit to nail down if degree length is a core impacting factor. For example, Finland has a superb secondary education system. Do their higher numeracy and literacy scores reflect the HE system, or is it simply that their student inputs into HE start from a much stronger position in numeracy and literacy? What we need here is a “value added” metric where we have data showing average value add at entry and exit; difficult to arrange but probably possible to somewhat infer. Similarly,… Read more »