There have been lots of articles already about universities and their responses to the Coronavirus. Many others have put it better than this but we can honestly say that those of us working in higher education now have never lived through times like this before in our sector.

Only a couple of months ago we were all thinking the future looked pretty tough and listing the challenges facing the sector as including the Brexit impact, financial shortfalls, pensions, industrial action, regulation, international student recruitment, over-regulation, the outcomes of the Augar review, unconditional offers, subject -level TEF, freedom of speech and more. These things all suddenly seem rather less important than they did.

Letting the days go by

In common with all Wonkhe readers it felt like the working world was turned upside down in just a few short weeks last month, as university crisis plans were enacted across the country and the vast majority of staff and most students left their campuses behind. Universities are fundamentally communities of scholars and not just the buildings that house them. But the buildings give us a sense of place, identity and solidity; the campus helps make our institutions what they are and generally facilitates rather than hinders the progression of learning and research. The working lives of 400,000 higher education staff have been regulated by the rhythm of the academic year, the steady ebb and flow of which has determined the pattern of activity for university communities – but now feels like it has been thrown completely out of kilter.

How did I get here?

I was taken by this recent HEPI piece about some of the similarities between the current crisis and that which hit universities over a century ago when the outbreak of the First World War came as a huge shock to an unprepared sector:

In 1914, the first, immediate impact was felt on student numbers. Existing male students volunteered to fight in large numbers; similarly, new male students due to enter their courses in September/October 1914 sought to defer their courses. In 1915, the position worsened further, as military recruitment efforts were stepped up, eventually leading to conscription. The result was a massive drop in overall student numbers.

Part of the response from institutions was to reassure their staff and students that their positions would be safeguarded. Universities also began to look for savings in any ways they could. They also contributed significantly to the war effort and ended up with additional financial support from government.

A key component of the contribution was, of course, for staff and students to sign up for the front. One of my predecessors as Registrar at the University of Nottingham, Thomas Porteous Black, was one of at least 23 members of staff from University College Nottingham to see frontline military action as part of the First World War and the most senior to be killed. As previously noted here the war hit the University College hard and the casualty rates were startling: 229 Nottingham OTC members together with other staff and students were killed and over 500 were wounded. Six staff didn’t return, among them Thomas Black.

Those were thoroughly remarkable and incredibly difficult times and, as the author noted, there are parallels with our current crisis. There is a more recent time too, albeit nowhere near as challenging as a wartime period, which has some similarities to the present situation.

Same as it ever was

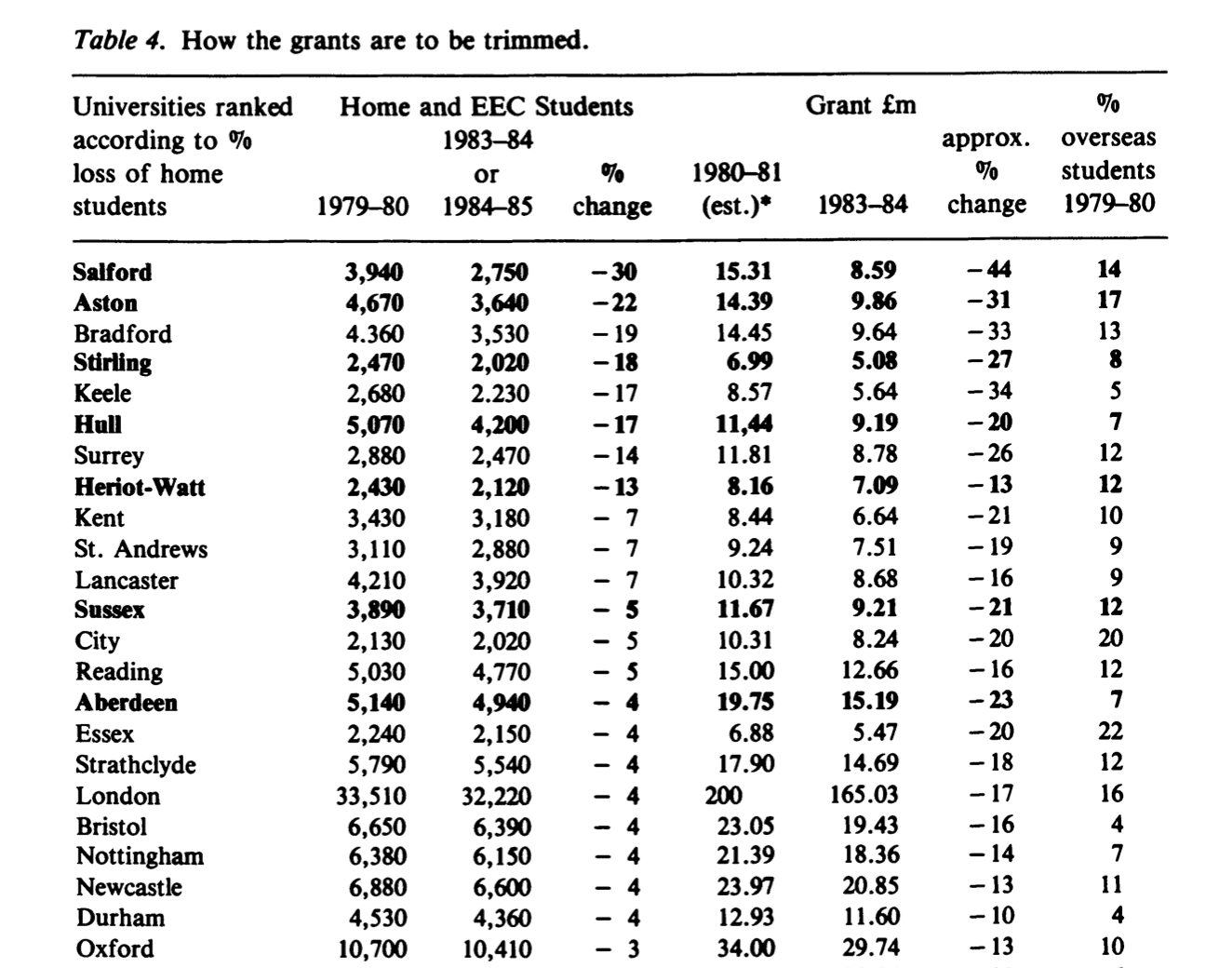

A long, long time ago in the late 1980s, when I started working in higher education, people and institutions still had the scars and were still feeling the aftershocks of the 1981 cuts to the sector. Back in 1981 the government imposed a 15% cut on HE which was then applied differentially across universities by the UGC – with some having single figure reductions and others facing much greater cuts. Salford University for example had a 44% reduction to its grant which led to 500 jobs being cut. The 1980s was a period of massive challenge for universities then and yet they all survived. It does rather feel that the sector is now facing its biggest test since those dark days. This table shows the scale of the reductions:

Although cuts were announced in 1981 the impact was felt over many years afterwards. A TV programme called Redbrick from 1986 captures life at Newcastle University at that time including some extraordinary footage of a crucial Senate meeting where a strategy for further contractions in provision is debated – mainly in the Arts and including the closure of Scandinavian Studies.

Whilst the cuts overall seem rather modest at 2% per year, there is much special pleading from Medicine, Science and Engineering at the Senate meeting – and views expressed by some in the room which are summarised by the Vice-Chancellor as “still hoping something will turn up”. The President of the Students’ Union at the time, Karl Holweger, argues passionately against all the cuts given the wider value of higher education and also makes the case for ending the binary divide.

Another professor characterises the choice for the university as either making cuts or having worse ones imposed by the UGC – a scenario he bizarrely compares to being “left in the light with the wise virgins or thrown into the dark room with the foolish ones”, a biblical reference which leads to much hilarity in the room from the entirely male Senate. It’s an excruciating reminder of another time.

It is an extraordinary artefact which I do recommend. Although barely 35 years old it genuinely feels like a different age altogether. The responses to the coming storm though are ones which many will recognise today, ranging from denial to fear to reluctant acceptance.

And you may say to yourself “My God! What have I done?”

There are some big difference with the challenges of the 1980s:

- We can see it coming – the nature of the worldwide crisis is such and the impact on every part of our national economy is so visible that it is (almost) impossible to deny that there is a huge storm approaching. Back in the 80s, universities simply did not expect that government would impose cuts as big as they did – most were modelling scenarios ranging from modest to zero growth and were utterly floored by the scale of the savings demanded.

- It’s not a committee of the great and the good of doubtful impartiality making the decisions based on questionable and opaque criteria.

- Although the expected huge loss of international student fee income (together with research, student accommodation and commercial income shortfalls) means the scale is much, much bigger overall than in the 1980s, most institutions are arguably better prepared to weather the storm.

- It is happening in one big hit rather than being spread over several years.

However, the massive size of the predicted income gap means that the sector does need help in the short term to manage the initial blow and transition to a different future.

How do I work this?

Following an initial flurry of unconditional offer making, since suspended, the response from the sector has been measured and co-ordinated. The package of measures will not please everyone but the set of responses pulled together by Universities UK has been submitted to government outlining the actions needed to be ensure universities can weather the serious financial challenges posed by Covid-19. The paper to ministers highlights the significant risk that the impact and capacity of higher education could be severely damaged without mitigations and support:

There are both short and long-term impacts currently facing universities:

- In the current financial year (2019-20) the sector is facing losses in the region of £790m from accommodation, catering and conference income as well as additional spend to support students learning online.

- In the next financial year (2020-21) the potential impact is extreme, with universities projecting a significant fall in international students and a potential rise in undergraduate home student deferrals.

- UUK modelling shows the risks to fee income from international (Non-EU and EU) students totally £6.9 billion across the UK higher education sector.

Without proactive action from both institutions and support from government, Universities UK warns that some universities would likely face financial failure, with severe impacts on their students, staff, local community and regional economy. Others would come close and be forced to reduce provision for students or to significant scale back research activities and capacity.

This is an even bigger crisis than the early 1980s. But there are grounds for optimism:

- If the package is fully or near fully implemented it gives the sector a fighting chance of recovery, across education and research.

- The package also enables the possibility of restructure and realignment in sector. It’s never happened before because it’s never been truly necessary and the incentive has never been sufficient; market-based reforms of HERA have failed to deliver what Coronavirus will.

- The way in which academic colleagues (and learning technologists and other professional staff supporting them) have moved so rapidly to online provision has been genuinely awe-inspiring

- Also the approach and adaptability of professional services colleagues has been nothing short of remarkable.

- The way our students have behaved and are looking to support communities and each other has been hugely impressive.

In addition, universities are doing all they can to contribute to the national effort against the Covid-19 outbreak. The sector is carrying out vital medical research into a possible vaccine; providing much-needed equipment, facilities and extra staff to frontline NHS services; and is exploring ways to support the people’s health and wellbeing through this difficult time.

A collection of case studies prepared by UUK forms part of the #WeAreTogether campaign and shows how everyone in our society benefits from universities. This inspiring list covers research, vaccines, and testing; resources and people power; helping people get through the crisis; and supporting students. Universities are also contributing to resilience in their local communities.

And you may ask yourself Am I right? Am I wrong?

In this extraordinary set of circumstances, universities are also trying to work out how we are going to adapt to this year’s recruitment round following the cancellation of A levels and GCSEs. We have to be confident though that universities will take all possible steps to ensure that whatever the next session turns out to be they will not be disadvantaged by all this – things might feel different for them but institutions will do all they can to give them the best possible experience.

There are a large number of institutions for which student fees are the largest part of their income and without it they will simply not be able to continue. We do nevertheless need universities to behave responsibly in their approach to this recruitment round, as set out in the UUK package, recognising that institutional survival is a very big deal indeed for thousands of staff, students, alumni and local communities as well as the wider sector.

These are the most challenging times any of us have ever faced in the past 40 years or even the last century or so. With the resilience and creativity of our staff and students already demonstrated to date we stand a chance of coming through it. Things won’t be the same but they might, against the odds, turn out to be better in all sorts of ways.

Paul, fanatistically insightful and thought provoking

Thank you Wendy!

Great piece Paul – thanks!

Cheers Andy

Great piece Paul. Hope you Rachel & the girls are all safe and well MCx

Thanks Mark!

Excellent work Paul: fa fa fa fa fa fa fa fa fa fa

Despite the similarities with 1914, and to a lesser, but graver time, 1981, this does not feel like a once in a lifetime experience, or maybe not. I fear we may need to adjust to a future where viruses will periodically wreck havoc. This is a timely piece, but we cannot return to business as usual as a sector, or the future looks bleak. The response to CV-19 has shown us how adaptable we can be, even at short notice. This must be a game-changer and a return to a new normality, or we’re on a road to nowhere.

‘following the cancellation of A levels and GCSEs’. I believe it is the examinations that are cancelled not the award of the qualification. Those students receiving these awards need the qualification to be valued to by Universities and employers.

[…] a drop in domestic student enrolment. On the other side, there is a threat to job security to over 400,000 people working in higher […]

Great piece Paul. Thanks for sharing some optimism at such a difficult time.